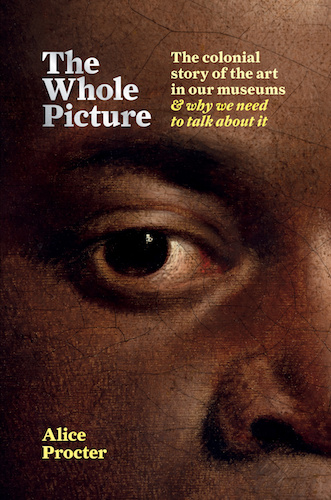

At the end of The Whole Picture: The colonial story of the art in our museums and why we need to talk about it, Alice Procter quotes from author Ursula R Le Guin:

‘Past events exist, after all, only in memory, which is a form of imagination. The event is real now, but once it’s then, it’s continuing reality is entirely up to us, depending on our energy and honesty.’

We are left with the thought that we can be active participants in the way we understand, interpret and remember our stories as individuals, institutions and communities: Regardless of whether these stories be housed in the ornate spaces of the past or contemporary spaces of steel and concrete we can question, object or disrupt the accepted narratives.

Beginning with a series of prompts, such as ‘What makes a museum?’ ‘What are you looking at inside?’ ‘What does the museum feel like?’ Procter then takes us on an ‘uncomfortable tour’ through the gallery spaces of Western history; spaces often motivated by cultural conditioning and influenced by wealth and power. But she also brings to our attention the power of artists and the general public to rewrite this narrative.

Divided into four chronological sections: The Palace, The Classroom, The Memorial and The Playground, Procter examines the motivations behind and reactions to a range of museums, galleries and memorials; the histories around these examples sometimes fascinating and often shocking.

Products of the European enlightenment, museums began in royal residences or aristocratic homes such as the Louvre, Prado and the Hermitage, becoming the prototypes for collections which followed. Appropriation of antiquity was common in the 18th and 19th centuries; the Elgin Marbles, sculptural reliefs taken by Thomas Bruce, 7th Earl of Elgin in 1803 from their original setting on the Parthenon and other Acropolis temples in Athens and ending up in the British Museum are examples of this. Ongoing battles for the return of these pieces along with many other objects have become long term issues between institutions and governments, calling for repatriation or restitution of past wrongs.

Pitt’s diamond, now housed in the Louvre, is an example of the integration of colonial power, synonymous with the East India Company of the 18th century, and the wealth and power of governments and institutions. Bought in India and incorporated into the French crown jewels it later became part of Napoleon’s sword hilt.

Marina Abramovic, a contemporary performance artist plays with this idea of reverence of association. In her title work The Artist is Present, 2010, at the MoMA retrospective, she spent every day during the exhibition in its atrium sitting under harsh flood lights where a visitor could sit opposite and experience her presence. Every visitor was photographed, with images posted online. Documentaries and a mocumentory were made, along with a novel, keeping her performance alive in popular consciousness.

Ways contemporary artists are reframing and interpreting the stories of these objects or artworks in museums is something that Procter regularly brings to our attention. The exhibition Mining the Museum, by Fred Wilson, 1992 has been a pivotal influence in the rethinking of other museum spaces and the objects on display; through the use of greater interpretive material, changes to labelling, renaming of objects, juxtaposing of narratives and so on, a different story is told. Staged at the Maryland Historical Society (MdHS), Wilson, an African American artist and activist, rearranged the space to represent stories of marginalised groups such as Native North Americans and African Americans. Over a few months the museum was rearranged to represent stories of discrimination, racism and enslavement. The exhibition confronted the viewer, asking difficult questions about how to interact with existing historical narratives.

The contemplation room, the final resting place for visitors to the Museum of African American History and Culture (NMAAHC) is a good place to finish as it is a quiet space. Somewhere to sit and consider the stories that have been told through object, photographs, artworks and text. Thirteen years in the making, the museum opened in 2016 and focuses not just on the ideology of remembrance but a way forward; presenting a timeline of American history to the present day. The contemplation room is a space with no answers, just gently running water and time for reflection.

A beautifully written and carefully researched book, Procter, a historian of material culture and the creator of Uncomfortable Art Tours, encourages the reader to think more critically and challenge the institutionalised paradigms of power and privilege in our museums and art galleries to instigate change.

A powerful and insightful exploration into the stories of our cultural heritage.

4 ½ stars out of 5

The Whole Picture: The colonial story of the art in our museums & why we need to talk about it by Alice Procter

Publisher: Hachette

ISBN: 9781788401555

Format: Hardcover

Categories: Non-Fiction, Australian

Pages: 288

Release Date: 31 March 2020

RRP: $39.99