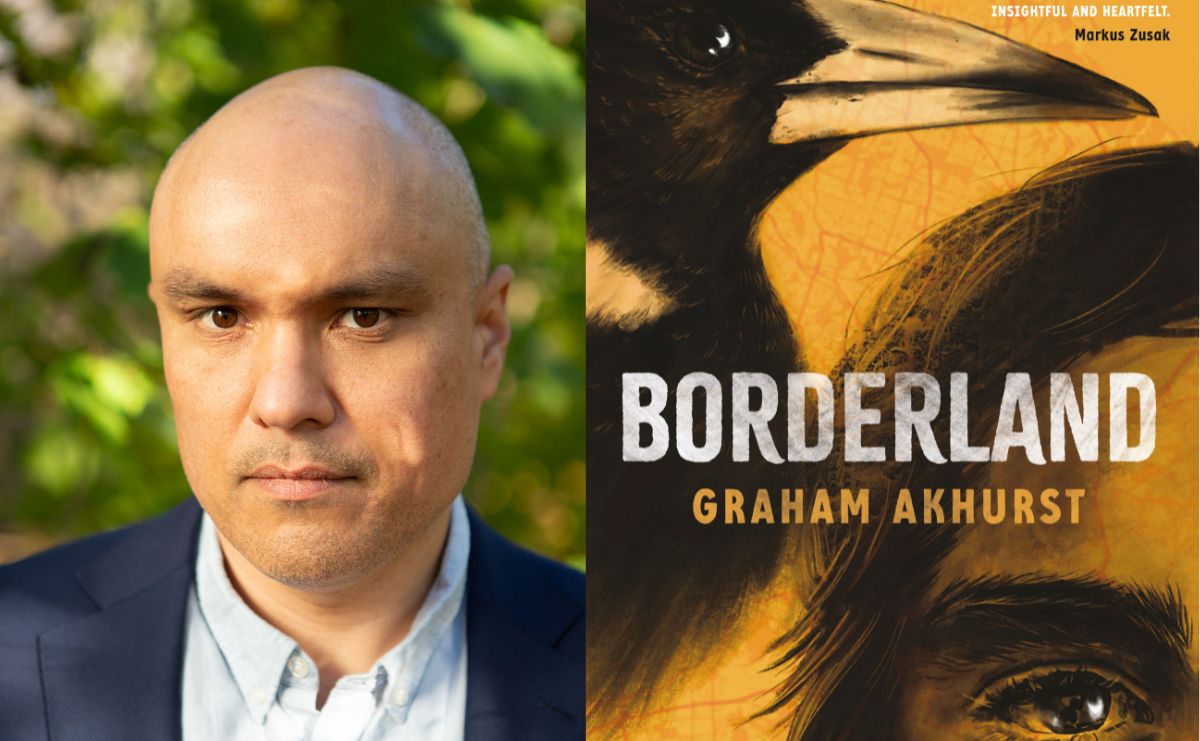

Graham Akhurst’s debut novel grapples with the borderland of adolescence and adulthood, educational institutions and freedom, ties to old friends and family and growing independence. It’s familiar territory for a young adult novel, featuring common themes of self-discovery, belonging and exploring the world and new relationships. But Borderland feels fresh and energetic – its context, especially in the wake of the outcome of the Voice referendum, is urgent and timely.

It is a familiar story but made for a contemporary time, with a plot and themes that will make it an ideal text for inclusion on secondary and tertiary curriculums alike.

Jono is a young Indigenous boy, uncertain of his heritage and of his place in the world: ‘I didn’t even know who my mob were or where my Country was,’ he states early in the novel. Everyone else, it seems to Jono, knows who they are, where they belong, what their future will look like.

His best friend, Jenny, finds strength and security in knowing that she is a Ngarabal woman; the ‘rich white kids’ at his private school are certain of their futures as wealthy, educated professionals. But Jono is everywhere an ‘impostor’, a ‘fraud’, a ‘dancing possum’.

He is, he thinks, only at his private school because of their ‘charity’, there to ‘show off how ‘socially conscious’ they are and all the wonderful things they are doing to ‘close the gap’ by helping the poor Blackfellas, and he is equally out of place at the Aboriginal Performing Arts College (APAC) he attends after finishing school, a ‘big city black’ without ‘community, language or tradition’.

This sense of unbelonging is underscored by the physical and verbal abuse Jono receives: at school and from his peers at APAC who refer to him as a ‘coconut’, a slur repeated by a group of Indigenous men who attack him on his walk home one afternoon.

These attacks from all sides mimic the repeated instances of magpie swooping Jono endures. In all cases, even when he fights back or runs, Jono experiences extreme symptoms of anxiety and panic. He also begins to hallucinate a strange, threatening, figure, half-dog, half-human, and fears for his sanity, eventually seeing a psychiatrist who prescribes medication to relieve his stress.

But the medication is only another form of running away. An opportunity to work on a small documentary explaining mining work and land protection rights to traditional owners initially seems to Jono as simply a chance to earn a decent wage while spending time with Jenny. Yet the work he undertakes is far more significant than he could have ever suspected.

Here Jono learns to ask questions, to think for himself rather than read a script, and to listen to stories and messages filtering through to him from the land and its spirits; only then does he begin to understand who he is, his place in the world and the impacts he might have. Just like the story of Wudun, who overcomes his fear of the ancestor spirits by taking on the form of the animals and becoming a protector of the land, so too does Jono manage his uncertainty and anxiety by embracing his connections to his mob and Country.

In its representation of the haunting spirit, Borderland engages with the legacy of the Australian Gothic – or perhaps more precisely what Mudrooroo (Colin Johnson) describes as ‘Maban Consciousness’ – the mysticism of Australian First Nations culture represented in its literature. In this sense, the Australian Gothic is not, ultimately, a source of anxiety, but of creative impetus. Like his confrontations with the magpie, Jono’s totem, which symbolises ‘death and the birth of a new life’, Jono finds meaning and purpose in wrestling with the uncomfortable.

Read: Book review: Late, Michael Fitzgerald

In its comedy, class consciousness and reflections on the power of black history to Australia’s future, Borderland reads like a meeting of Leah Purcell’s The Drover’s Wife, Vivienne Cleven’s Bitin’ Back and Christos Tsiolkas’ Barracuda. Its open ending constitutes a breathless sense of hope and opportunity – for Jono, for First Nations Australians and for emerging young adult literature.

Borderland, Graham Akhurst

Publisher: UWAP

ISBN: 9781760802646

Pages: 236pp

Publication Date: 1 October 2023

RRP: $22.99