It’s the late 70s and early 80s. It’s a world of foster kids. It’s a world of fathers in prison and mothers never known. It’s a world of dole cheques, of Benson and Hedges, of overdoses. It’s a world of kids playing Lindy or baby Azaria Chamberlain, then going missing themselves.

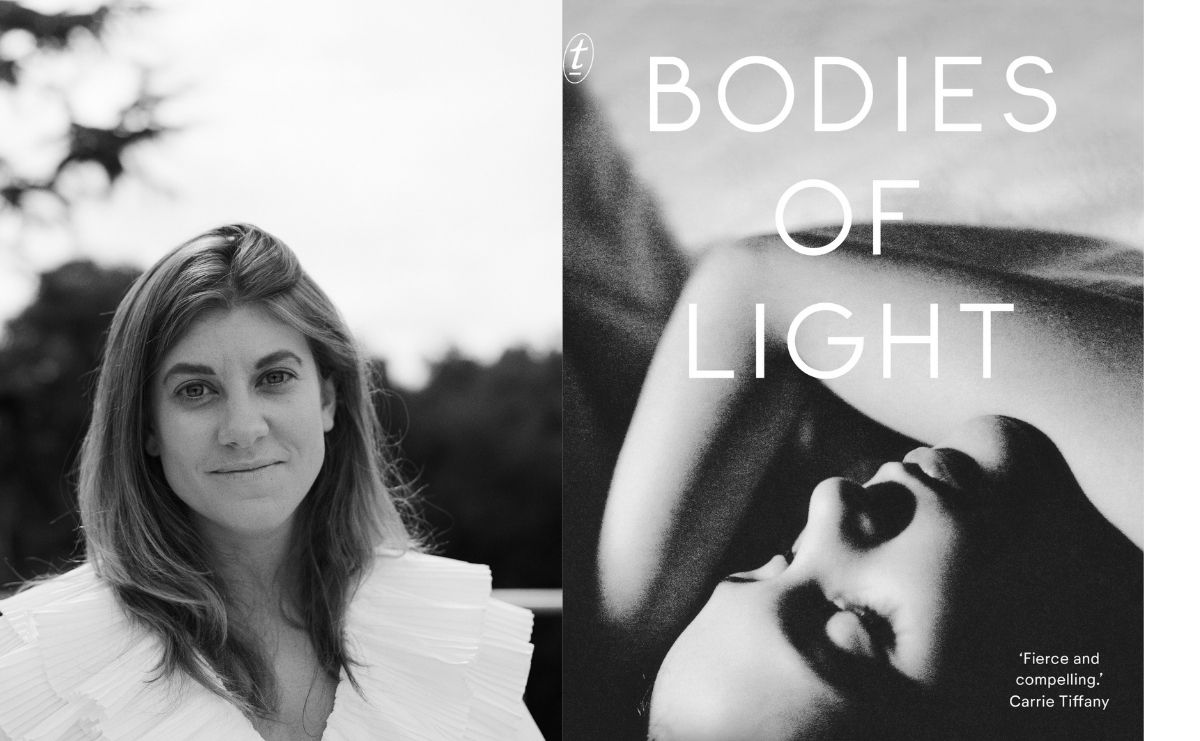

This is where we begin Jennifer Down’s Bodies of Light. Maggie – also to be known throughout the novel as Josie, Chook and Holly – has grown up in a world of washouts. Sexually assaulted at an unspeakably young age, with a father holed up in prison and a mother dead of an overdose, now drifting between foster homes, carers, guardians and schools, her early life is a continuous fight against the programming of her surroundings. It’s a desolate struggle for normalcy, an attempt to transcend the unassailability of trauma and the strictures of socio-culture.

Indeed, that seems an apt description for the book’s central thrust: one woman’s attempt to conquer the past. There is no real inciting incident. It’s simply a chronology, a kind of event-punctuated, fastidious retelling of one’s past pain, a pain which, no matter how many times Maggie attempts to reinvent herself anew, cannot simply be waved away. Down insists on it going bone-deep.

If it all sounds a little bleak, that’s because it is. Down’s writing is descriptively unflinching, right the way through. On a stylistic level she reaches with great persistence for a kind of memory-infused prose. Thoughts and images interpolate, floating up and in between real-time action. Minute details are attentively jotted down one after another. Her sentences maintain a deceiving simplicity of appearance, with Down instead focusing on the gaps between sentences, the transition from one to another, attempting to foreground the capricious workings of Maggie’s mind. Indeed, the gaps between scenes are also crucial; the cinematic, scene-heavy style of the book’s structure emphasizes the interstitial spaces connecting one moment to the next. This, I assume, is a means of reflecting the slipperiness of memory, the imperfection of recollection, the way in which some moments live on with crystal clarity in our minds while everything before and after dissolves into nothingness. Maggie admits as much early in the book, as she recalls her time living on Mystic Court in Eumemmerring. ‘Mystic Court is like a floater in my eye, or the places at the edge of your vision that go spotty with darkness right before you pass out. Apricot, duffel coat, Eskimo Pie, patience.’

Though Down is a committed practitioner of her memoria schtick, in the course of 425 pages it’s prone to come off as over-deliberated and programmatic. A number of scenes are downright overwritten. Quotation marks are excised throughout, all dialogue folded into its surrounding prose – a stylistic flourish particularly grating and unnecessary. Though executed with an undeniable degree of precision, it’s a mannered, writerly style which may or may not get on your nerves. It certainly got on mine.

In a broader perspectival sense, the book confounds. Why exactly is this story being penned? Why is Maggie so dutifully relitigating her past, reliving all her avarices, her moments of self-destruction, her crushing pain? The question is never asked. Nor is enough emphasis placed on the idiosyncrasies of Maggie’s narration. The entire story is told in first-person, and yet no strong voice emerges. Reading an essay Down wrote for LitHub, you quickly realise that the narration of Bodies of Light is, in fact, Down’s voice, not Maggie’s. Yet more proof that just because you put an ‘I’ before a verb doesn’t inherently make the voice authentic, nor sonorous nor alive. It needs contours. This is a stylistic point Down seems to have overlooked.

Read: Exhibition review: Bark Ladies, NGV International

What we can praise the book for, however, is its grand scope, and the unwavering commitment of its vision. It traverses four decades and three countries with a great deal of ease, and though the New Zealand section never quite convinces, the action spanning the other two countries is so rich, so alive with real characters, that the experience quickly becomes immersive. And there are moments between these ultra-real characters which Down examines with unassailable elegance and tact. The ambiguity of love, for one. ‘I loved him,’ Maggie says, ‘with an intensity that scared me. I built a temple of us in my mind. The initials of our names were adjacent in the alphabet and I thought that was a sign. I was nostalgic for things that had not yet happened.’ Spot on.

But Maggie’s quest for love is dwarfed by a greater need to purify herself of her emotions, to tear down the façade, to reinvent herself. Maggie is yet another protagonist in a contemporary piece of literature who wants to disappear. (It began with Less Than Zero, and I feel like they’re everywhere now.) What Bodies of Light ultimately asks, however, is the extent to which we can really do so. Though it’s not such an interesting question, and though some of Down’s answers to it are more of the same stuff we usually get – we can’t outrun the past, our memory defines us, and so on – the cavernous depth with which Down expresses Maggie’s need to rebuild herself is one of the book’s most significant achievements. If you can overcome the stylistic scholasticism, there’s a rich vein of human vulnerability to tap into, a vein from which many of us could derive at least one or two moments of illumination.

Bodies of Light by Jennifer Down

Publisher: Text

ISBN: 9781925773590

Format: Paperback

Pages: 427pp

Publication: 28 September 2021

RRP: $32.99