West Australian Ballet’s Ballet at the Quarry is a perennial Perth Festival event and the company’s traditional season opener. It’s also a fascinating intersection of classic artform and old industry: the grace, poise and power of classically trained ballet dancers contained within the rough walls of a former limestone quarry, which was transformed into an amphitheatre in 1986.

Ballet at the Quarry: Incandescence – quick links

Ihsan Rustem’s Incandescence

The 33rd edition of Ballet at the Quarry: Incandescence, featuring four world premieres, is named after the fourth and final piece on the bill, a striking new work by British choreographer Ihsan Rustem, which is notable for being just the second piece – among more than 60 choreographic works Rustem has created to date – for dancers on pointe.

Its bold, free-flowing and distinctive group dynamics contrast beautifully with a series of expressive duets exploring a range of human emotions and connections, and featuring bodies interlocking, manipulating and parting. Such sequences are set to songs from Rustem’s youth, including Bells for Her by Tori Amos (1994) and Christobal Tapia De Veer’s The Girl with all the Gifts (2017), and collectively, focus on unity and connection.

The exception – and also the most striking of Incandescence’s duets – is a compelling pas des deux danced by two shirtless male dancers, Ludovico Di Ubaldo and Charles Dashwood, performed to Sam Fender’s aching 2020 cover of Amy Winehouse’s beautiful, painful break-up song, Back to Black. The song’s lyrics, (‘We only said goodbye with words/I died a hundred times/You go back to her/And I go back to…’), take on extra poignancy, given the inference that one of the men is leaving to go back to his former, female, lover.

Notably, Dashwood and Di Ubaldo are the only dancers in Incandescence who cross a vertical boundary drawn in light near the edge of the stage (created by a suspended length of LED lights in clear plastic tubing which forms an arrowhead-shaped structure that both frames and disrupts the dancers’ movements). The lighting design literally comes between the pair several times as they pass beneath it in turn – an echo or acknowledgement, perhaps, of the drug-driven ruptures of Winehouse’s original song, in which the lovers’ incompatible addictions (‘You love blow [cocaine] and I love puff [marijuana]’) help drive them apart. The sequence can also be read as an artful evocation of the ways queer relationships disrupt traditional heterosexual paradigms and relationship t

Repeated visual motifs

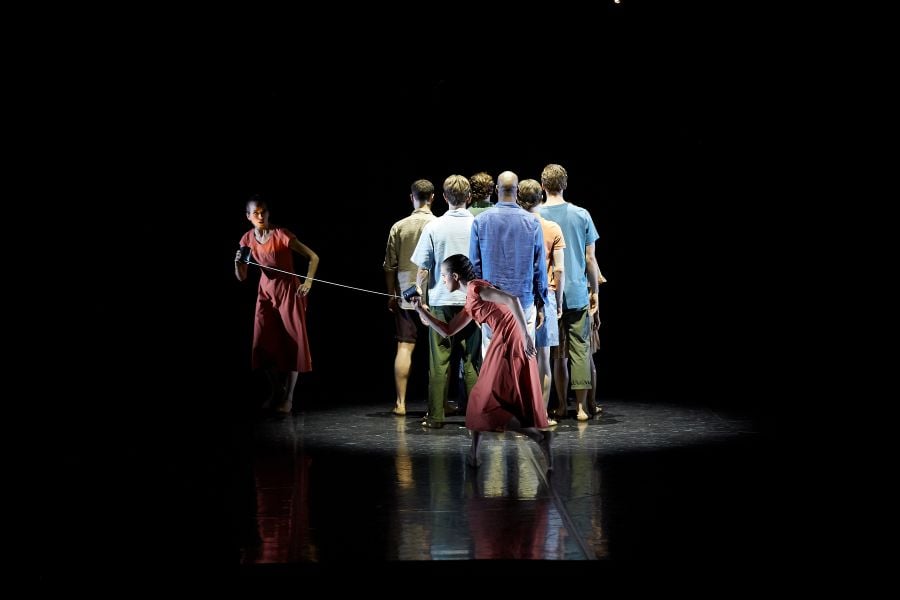

The visual motif of extended cables, ropes and ribbons, seen in the suspended lights of Rustem’s Incandescence, is echoed throughout the works presented at this year’s Ballet at the Quarry program, as is the use of fabric.

In Tim Harbour’s opening piece, Once and Future, a bedsheet hanging on the clothesline becomes a tablecloth elsewhere in the work. In addition to the clothesline itself, a length of cord also appears, connecting two ballerinas dressed in identical salmon-coloured garments (costumes by Harbour also) as they circle and temporarily constrain the other dancers – the cord perhaps representing a thread of thought or a memory connecting one of the women to her actions in the past. Another possibility is that one woman is haunting the other, though whether literally or metaphorically is impossible to know in a piece as dense as this somewhat unsatisfying production.

Choreographically, Harbour’s vocabulary ranges from familiar and formal balletic forms, including ballet mime, to a looser, more contemporary vernacular. One moment dancers huddle in nervous groups, the next they prowl menacingly across the stage, accompanied by Ulrich Müller’s sometimes sonorous but too often unsubtly filmic score.

Once and Future feels frustratingly complex, as if Harbour’s imagination has over-populated the work with too many ideas, images and themes. The end result is a piece that never fully coheres, and which calls out for either rigorous dramaturgy to condense the work, or expansion into a longer piece so that its many ideas have more room to breathe.

Company members choreograph on their peers

The evening’s familiar visual motifs of ribbons and sheets of fabric are repeated in the two new works choreographed by members of the Company: Soloist Polly Hilton’s Paper Moon, which follows Harbour’s Once and Future, and after the interval, Principal Artist Chihiro Nomura’s Night Symphony Colours.

Children playing make-believe are silhouetted behind a hanging cloth in the opening sequence of Paper Moon, Hilton’s mainstage solo debut; later, a ribbon is cut with an outsize pair of scissors. Exploring childhood dreams – especially dreams that remain unfulfilled as we age – it’s a fluid and considered work populated by archetypal characters (a prince, a hunter, a princess) and skilfully performed. Here, as elsewhere, Damien Cooper’s lighting design – seen in all four productions – is striking and superb, such as a sudden lighting transition evoking the ‘golden hour’ late in the piece; Hilton’s imaginative costume designs are equally exquisite.

Although beautiful, Paper Moon also feels slightly insubstantial; more intensity in the clean, sharp choreography, or perhaps increasing the number of dancers so that the stage feels less empty, would strengthen the work.

Read: Prima Facie review: a relentless force of a play

Nomura’s Night Symphony Colours, the first act after interval, is a showcase of traditional ballet technique superbly performed – with scattered bursts of applause throughout the audience at intervals testament to the five colourfully costumed dancers’ skilled execution of the choreography.

A spirited work, in which Nomura has manifested her dream of creating ‘a piece where the night sky becomes a canvas and the dancers’ movements are strokes of vivid colour’, Night Symphony Colours nonetheless suffers in comparison to the other, meatier works in the program. A ‘behind the scenes’ style opening, in which we see the dancers come together for a group hug and then leave – one exuberantly – before the house lights dim and the work proper begins, is its only real break with tradition. More moments like this – more playful or provocative meat on the piece’s undeniably beautiful bones – would ensure a more memorable work.

Collectively, Ballet at the Quarry: Incandescence is a well-balanced program of new balletic works, with Rustem’s titular work being the clear highlight. Programmed by Guest Artistic Director David McAllister, who stewarded the company in 2024 and 2025 until Leanne Stojmenov took over the reins in January this year, it is a strong opener to the West Australian Ballet’s 2026 season and was warmly received by the loyal Perth audience.

Ballet at the Quarry: Incandescence is a West Australian Ballet production presented with Perth Festival, and continues at Quarry Amphitheatre, Mooro/City Beach until 28 February.

Richard Watts visited Perth as a guest of Perth Festival.