‘I like dwarves’, read the subtitle of the Instagram video. That first line made me stop my doom scrolling. The algorithm picked out something it thought I would like. I follow a lot of comedians – they create my third-favourite form of social media content, after “snake identification” and “people incorrectly correcting other people”.

But I knew the algorithm got this one wrong. The so-called comedian was talking about me. I got the sense he liked me in the “shout at me out the car window” manner rather than the “would love to have a glass of wine next to the fire” sort of way. But over 200,000 people had clicked the heart emoji on the post, so I was somewhat curious.

‘I know you’re not meant to say “dwarf” anymore,’ he said. ‘You’re meant to say “little people”. But I don’t like the term “little people” one bit. Because “little” – bit patronising.’

He paused, a smirk entering the corner of his mouth.

‘And “people”? Come on, that’s a stretch.’

I’ll stop his routine there. It gets worse, but those words hit me like a truck falling from a skyscraper. This person thinks it’s a stretch that I’m a person? And others are laughing at the suggestion?

People have a long history of denying that other people are people. It tends to have appalling results.

To be fair, I grew up thinking I was a fantasy character. This is what it’s like for so many people with a disability – the fictional characters they most resemble are usually hidden from view in attics or caves or deep inside the woods. Sometimes villains, always oddities, they rarely have personal autonomy and certainly never get the real rewards of the fairy-tale ending.

I was an Oompa Loompa – orange-faced and beholden to the whims of an eccentric confectionary billionaire.

I was one of Snow White’s seven dwarfs, defined by a single emotion and never in the picture for a normal human relationship.

A bit later, I was one of Tolkien’s dwarves. It was a little more exciting, but they were ultimately still strange creatures.

The first bit of The Hobbit I read as a kid was the foreword.

In English, the only correct plural of ‘dwarf’ is ‘dwarfs’ and the adjective is ‘dwarfish’. In this story ‘dwarves’ and ‘dwarvish’ are used, but only when speaking of the ancient people to whom Thorin Oakenshield and his companions belonged.

Foreword to The Hobbit, J R R Tolkein

This is one reason I stopped when I saw that Instagram video. Whoever had written the subtitles thought of me as belonging to some ancient fantasy tribe rather than my local human community.

Around the time I was reading The Hobbit, I learned that I was not only a fantasy character, but also the butt of countless jokes.

I was sitting in the lounge room watching my favourite comedians dissect the week’s news. They were playing a game in which the two teams had to guess the story based on the headline. I laughed along with everyone else until a headline flashed up that made my heart sink.

‘WTF? Beautiful people meet Hank the angry drunken dwarf.’

Jokes flooded in about the possibility of Hank’s identity. Could the diminutive host secretly be Hank?

‘No way. He might be angry, perhaps even drunk, but the beautiful people don’t go near him.’

The audience chuckled.

‘I know. People magazine did a poll of the world’s most beautiful people. They assumed the winner would be Leo DiCaprio. The internet had other ideas and voted in a dwarf called Hank, who has a penchant for booze.’

‘Three points!’

The crowd cheered.

My mum asked if I was OK. I grunted that I was. But I wasn’t. This was the way the world saw me. It defined how I saw myself.

These incidents have come up throughout my life. Some pub holds a dwarf-tossing competition. Someone organises a ‘midget race’ at the Caulfield Cup and the punters love it. A ‘professional dwarf entertainer’ is set alight by a footy player and the league boss laughs. Sometimes the outrage industry puts up a fuss. But it keeps happening.

Despite this, it’s clear that mainstream media representation has changed for the better. Actors on my screen, the likes of Peter Dinklage, Francesca Mills or Australia’s Kiruna Stamell, provide nuanced portrayals of strong characters. The actors and their on-screen personas are proud of who they are, but not defined by their height.

When Disney came out with a new Snow White film, the dwarf characters remained, but at least we had the likes of Dinklage calling them ‘f***ing backwards’.

But it hit me as I watched that Instagram video that people are still making the same awful jokes. And even more people are laughing at them. Scrolling through the comedian’s account, I realised that this was the most popular video out of hundreds.

Read: How can publishers best support the authors of trauma memoirs

Outrage is not working. Shaming is not working – even telling you where to find this video would be counterproductive, because part of you wants to hear the rest of his bit, right? Let me assure you that it doesn’t get any better.

There is no quick fix to this kind of humiliation.

I get hope when I walk into my daughter’s kindergarten. In the first week of the year, the other kids pulled on their parents’ jackets and asked if I was real or if I was a dad or why this kid had a beard. Now they come up to me and show me their artwork. Their ability to see people as people gives me hope.

As a community, we have a responsibility to show the next generation the beauty in the diversity of all people. Nobody should grow up thinking they’re a punchline to a joke unless they wrote the joke themselves. In that case, I look forward to seeing their comedy routine pop up in my feed.

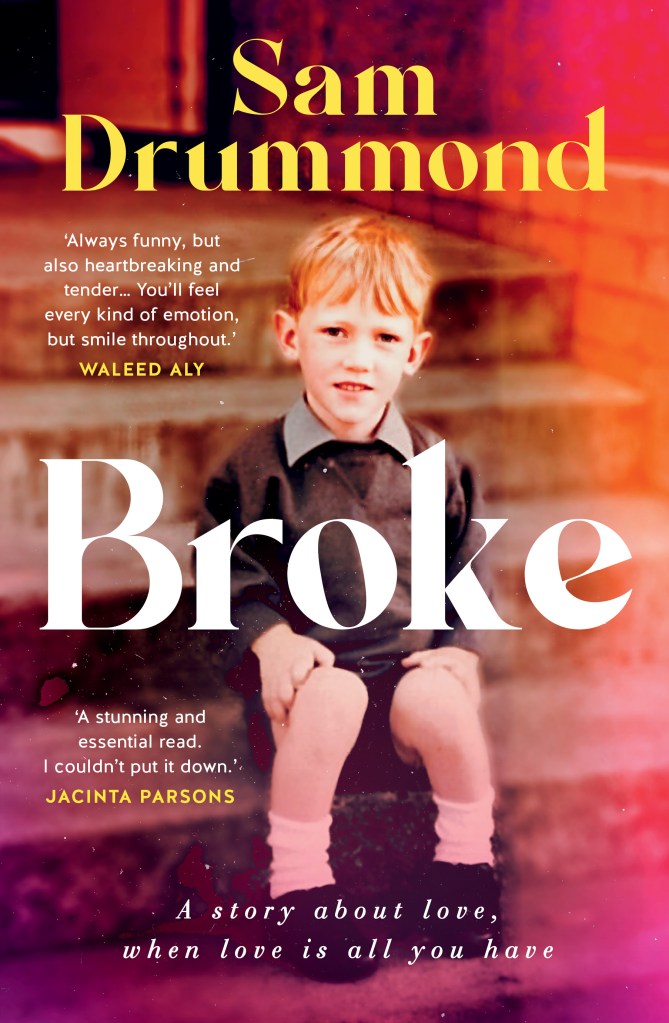

Sam Drummond’s memoir Broke is out now (Affirm Press).