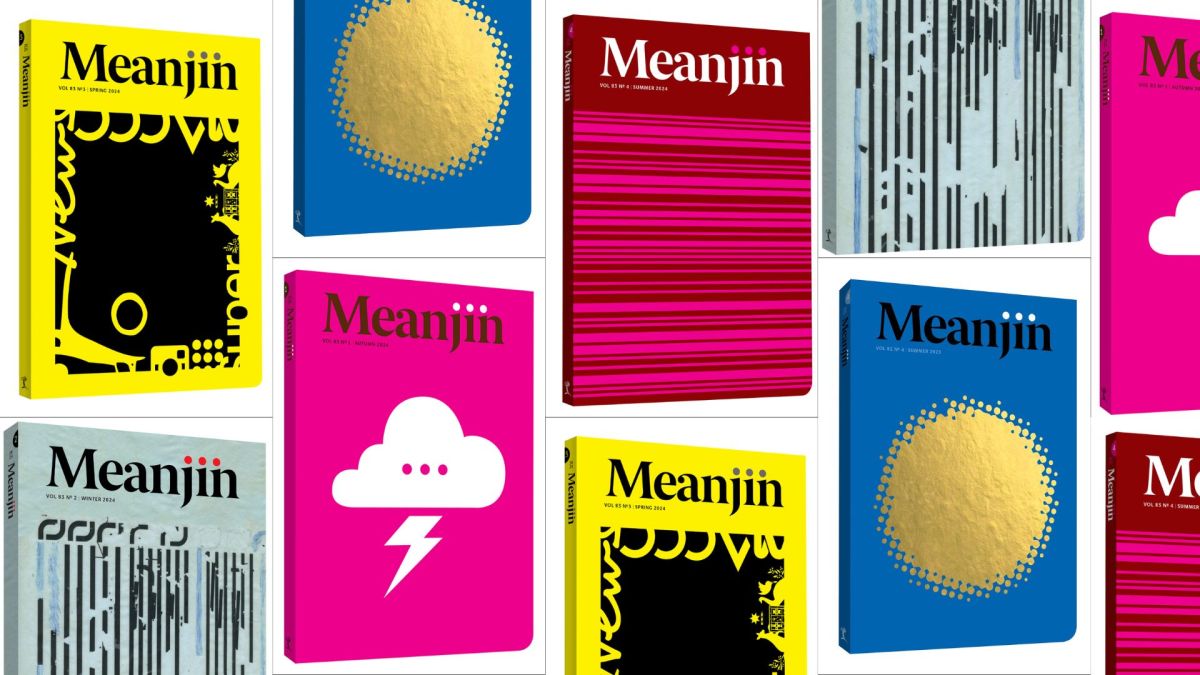

Yesterday’s news that longstanding literary magazine Meanjin is closing after more than 80 years of publishing is devastating.

Literary magazines are the lifeblood of Australian literature. They enable emerging writers to create and develop a track record of publications, respond to local and national concerns in creative and agile ways, and provide an income for writers and arts workers.

And yet Meanjin’s summer edition in December, set to celebrate eight decades of Australian writing, will be its last.

Meanjin: 1940–2025

The journal, originally titled Meanjin Papers: Contemporary Queensland Verse, was founded by editor Clem Christensen in 1940, and was named for the Yuggera word for the place on which Brisbane grew.

Literary critic Tony Gibbs describes its first edition as ‘a sheaf of eight pages containing a fey little poem by Brian Vrepont (‘Apple Blossoms’), a sea-shanty by the editor, Clement Christesen, other unobtrusive pieces, the whole adding up to a publication that might more appropriately have been titled A Brisbane Yellow Book’.

ArtsHub: Meanjin, Australia’s second oldest literary journal, to close

Five years later, The University of Melbourne invited Meanjin to relocate to Melbourne – where it still resides. Over three quarters of a century, it has published writing by formidable Australian authors such as Alexis Wright, Gwen Harwood, Judith Wright, Jennifer Mills, Bruce Pascoe, Michelle de Kretser, Alex Miller, Sarah Holland-Batt, Roberta Sykes, Alan Marshall, Oodgeroo Noonuccal and Helen Garner.

In 2008, the journal became an editorially independent imprint of Melbourne University Publishing (MUP), which has now ordered its closure on ‘purely financial grounds’.

Meanjin: Australian literary heritage

Not only are we losing a critical feature of Australian literary heritage, but editor Esther Anatolitis and deputy editor Eli McLean have reportedly lost their jobs. As former editor of the Sydney Review of Books Catriona Menzies-Pike wrote in her 2023 report with Samuel Ryan, Literary Journals in Australia, insecure work is one of the reasons for a lack of diversity in literary organisations. As an author herself and champion of Australian writing and writers, the loss of Antaolitis’ commentary and editorial influence will be profound.

Meanjin has also been a mouthpiece for many in the literary sector. Jessica Alice, the driver behind the creation of new South Australian literary magazine Splinter and now director of the Byron Writers Festival, wrote in February 2023 of the neglect of the Australian literary ecosystem, particularly under the Liberal government.

She observed that where literary magazines such as Voiceworks, which focus on young writers, ‘serve as a training ground for the next generation of writers, literary journals are themselves the engine of literary culture, allowing for an experimentation with style, a testing of ideas and development of a uniquely Australian voice’.

In a world of increasing polarisation and extremism, of large language models such as Chat GPT that threaten to homogenise writing and undermine writers’ livelihoods, such a voice – or voices – are needed more than ever.

ArtsHub: The Productivity Commission just advocated for theft and I’m f**king livid

Through short stories, poetry, essays, and pieces of memoir, literary magazines provide a diverse range of writing that speaks to multifaceted identities in 21st-century Australia. They are also laboratories: places where writers can try out forms and styles which may not be accepted by the broader publishing industry.

Not only this, but literary magazines are generally the first place in which writers publish. Without publications on their curriculum vitae, publishers and agents are often less likely to take emerging writers seriously.

The demise of Australia’s second oldest literary magazine (following on the heels of the oldest, Southerly, established just a year earlier, in 1939), represents the loss of opportunity for Australia’s future writers. It also signals an attenuation of ‘the quality, quantity and diversity of publishing and editorial initiatives in Melbourne’ – one of the reasons why Melbourne was designated a UNESCO city of literature.

Meanjin: universities waging war

A number of universities are waging war against degrees that encourage creative expression and critical thinking. The Australian National University has threatened to close the Humanities Research Centre and the Australian National Dictionary Centre, and to cut funding to the School of Music and Australian Dictionary of Biography.

Macquarie University, the University of Wollongong, and the University of Tasmania have also cut courses. In late 2024, Southern Cross University closed its degrees in contemporary music, art and design and digital media.

Many have cited the introduction of the Morrison government’s Job Ready Graduates fee model, which increased the cost of an arts degree, as a contributing factor in the decline in enrolments.

The assault upon the humanities harms not only students, but also the communities which these institutions serve. In shuttering Meanjin, MUP, as an arm of the University of Melbourne, is doing a great disservice not only to Australian writers, but also the readers in their community.

Jessica Alice, in her 2023 essay, was responding to the recent release of the National Cultural Policy Revive: a place for every story, a story for every place. She closes her essay with the statement: ‘What comes next requires fortitude and imagination to create a truly vibrant literary culture.’

Yet bean counting does not leave space to quantify the intangible value of creative expression, critical thinking, and the pleasures of reading and imagining.

Having invited Meanjin to Melbourne, the world’s second UNESCO City of Literature, it seems poor form to show the journal the door. Is it too late to hope for another to open?

Jessica White is the author of Silence is my Habitat: Ecobiographical essays (Upswell) published 1 October 2025.