‘As a woman, 50 is the age for peak mansplaining,’ says NSW-based visual artist and award-winning poet Judith Nangala Crispin. That was the age at which she set off on a remarkable journey, taking her to some of the most remote parts of central Australia. ‘The blokes who care about you explain that if you go out in the desert alone, you’ll need to be rescued … And that your rescuer will probably be Ivan Milat.’

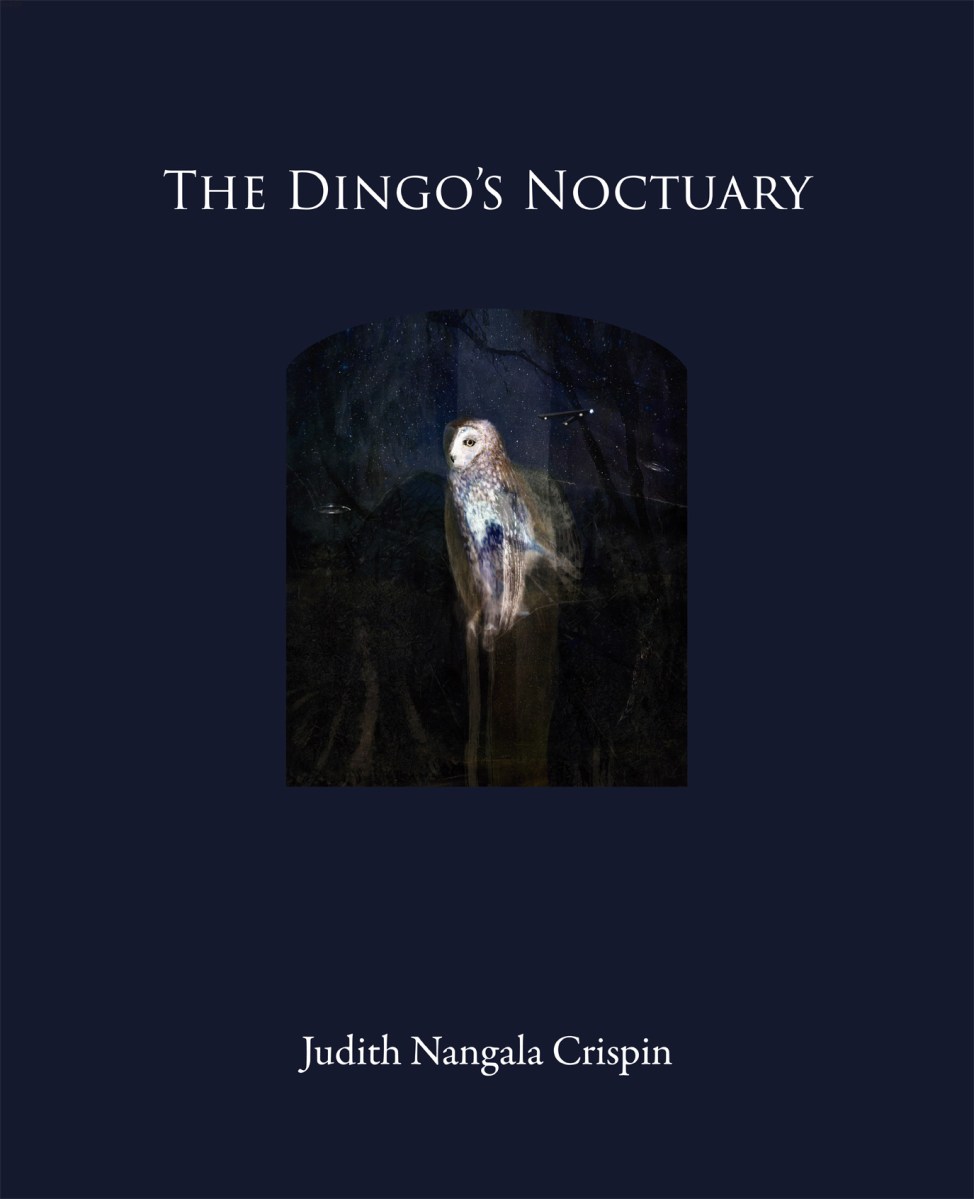

Celebrated for her words, and her almost impossibly beautiful artworks that grant a glorious afterlife to animals who have shuffled off their mortal coil, her new book, The Dingo’s Noctuary, sets soul-searching questions about mortality, identity and belonging against a central Australian backdrop.

The result is about as far from a dry, theoretical reflection on being a woman ‘in the prime of her invisibility’ as you could imagine – it’s a remarkably visceral, and visual, record of lived experience.

Gunning her motorbike through the remote Tanami desert north-west of Alice Springs – as Nangala Crispin did 37 times while writing Noctuary – alone but for the company of her biker-goggles wearing dingo-dog Moon, sounds like one helluva bad-ass way to give the middle finger to middle-age. But within minutes of meeting Nangala Crispin it’s clear she is, indeed, a bonafide bad-ass.

‘I spent so much time thinking about all the things I couldn’t do,’ she says now, remembering her state of mind before that initial journey. ‘And then one day I thought: fuck it. I’m going. I’m going on my own.’

In conversation, Nangala Crispin casually references Wittgenstein and Warlpiri wisdom with a beguiling mixture of easiness and poetic precision. There’s a fierce, no-nonsenseness to her, tempered with a deeply philosophical and spiritual way of seeing and experiencing the world. She says this was inevitable.

‘I’m the daughter of a judge and a priest, so I didn’t really have many options,’ she mentions, laughing.

Her journey across some of the most remote parts of Australia – which began in 2011 partly as an act of middle-aged-woman rebellion, partly as a search for belonging – became fodder for her third book, The Dingo’s Noctuary, which was published recently.

The Dingo’s Noctuary – quick links

The Dingo’s Noctuary is a hardback, hard-birthed collection of verse poetry and photographic portraits, steeped in the silence and exhaust fumes of those many motorcycle trips Nangala Crispin took across the central Australian desert – one of which fell foul of the law of unintended consequences.

On her thirty-seventh crossing, in 2021, she was hit by a woman driving an SUV, leading to a brain injury, four years of rehabilitation, and an ongoing struggle with computer screens that meant half of The Dingo’s Noctuary was written on a 1966 Olympia Splendid 33 travel typewriter.

Incredibly, for a book so accomplished and of such ambition, The Dingo’s Noctuary wasn’t what she’d originally planned to write.

A love poem to the desert and a debt, repaid

‘I intended to write a really Zen book about birds,’ she says. ‘But it’s turned into this sort of giant love poem to the Tanami desert and its Custodians, the Warlpiri people.’

‘When I was on this sort of 20-year journey of trying to trace my family’s Indigenous ancestry, it was the Warlpiri who took me in and befriended me. I wanted to find a way to repay my debt to them.’

Repaying that debt, for Nangala Crispin, was about sharing her love for Warlpiri Country through the book – all of the proceeds from which will go to The Purple House, an Aboriginal community-controlled charity that provides on-Country kidney dialysis treatment to people in remote communities. The book’s publisher, Puncher and Wattman, is also matching the donations raised by the book – quite a gift for a small publisher in a competitive industry where it’s notoriously tough to make a buck.

These remote communities experience rates of chronic kidney disease 30 times the Australian average – a reality Nangala Crispin knows only too well, having lost Warlpiri friends to kidney failure while writing the book – and so the donation to Purple House felt like something tangible she could do to make a difference.

‘You feel like you’re on this treadmill of survival all the time,’ she says. ‘And so, it felt a bit freeing in a way to say, “Yeah, you know what, we’re poor anyway. We’ll just stay poor”. Because the rest of the time, you’re trying to convince art funders that literature’s worth supporting. But when you take it back with your own hand, you feel like you’ve got some of the power back. The art is for what you want it to be for.

‘It’s about community more than anything.’

A family secret and accepting ambivalence

In one of the poems in The Dingo’s Noctuary, Nangala Crispin tells the story of learning about Charlotte – her grandfather’s grandmother, a Bpangerang woman, from around the Murray River – whose existence had been erased from her family history. Revealed to her in a letter from her uncle shortly before his death, the secret shook Nangala Crispin to her core. ‘When the lie unravels it takes your breath away’, she writes.

‘In the beginning, what I was looking for was to try to restore [Charlotte] back to our family tree,’ she says. ‘I was really looking for belonging or identity. And I didn’t get that. What I ended up really getting was friendship and this feeling of being loved and loving people. And I realised, if you’ve got that, then the other stuff doesn’t matter.’

Adopted by the Warlpiri, in 2011, she was given the skin name ‘Nangala’ – the ‘skin name’ being the familiar term of reference in Warlpiri culture. Conversations with her Warlpiri friends, many of whom are written about in The Dingo’s Noctuary, helped Nangala Crispin understand that what she’d previously been chasing – pinning down her history and mapping her family tree – was, in essence, a coloniser’s way of thinking.

‘I spent a lot of time with these really great Warlpiri women, painters, who said to me the important thing is the moving forward. You go out into the Country and you speak to Country, and Country speaks back, and you try to honour that connection as best you can.’

‘I’m a middle-aged woman,’ she says. ‘I’m not old and I’m not young, and I’m not black and I’m not white. I’m something in the middle and I’m a process that’s unfolding. I don’t know what direction it’s going to go in and I don’t need to know that.’

An Australian epic poem, an Odyssey of woman and Country

In its deftness of language, the vastness and universality of its themes, The Dingo’s Noctuary reads like an epic poem with a distinctly Australian feel. We can’t help but get a sense of Nangala Crispin’s yearning for a sense of home, the significance of her friendships with the Warlpiri, and there are visions, ghosts and omens.

Her descriptions of place jump from the macro to micro, referencing the movement of NASA’s Cassini space probe and the changing constellations – both the bright stars of the Greek zodiac and the Emu in the Sky dark nebulae of First Nations astronomy – conjuring the enormity of the Tanami desert’s night sky: a place where stars fall from the heavens and its easy to believe in aliens.

Nangala Crispin’s affinity for the cosmos in its entirety informs her work, but she has a special connection to our closest planetary body. Her mongrel dingo-dog’s Warlpiri name is Kirndangi, meaning ‘moon’. Saved from a cull, he was given to her as a pup on the verge of death.

Full of mange and with a mouthful of maggots, Moon pulled through under her care, and – in carrier cage and goggles – became her travelling companion across most of the journeys she took to write the book.

And now, in what was, to put it mildly, an unexpected turn of events for Nangala Crispin, works from The Dingo’s Noctuary are resting comfortably on the real-life moon as part of the Lunar Codex time capsule archive, a digitised repository of artworks by more than 50,000 contemporary artists, writers, musicians and filmmakers.

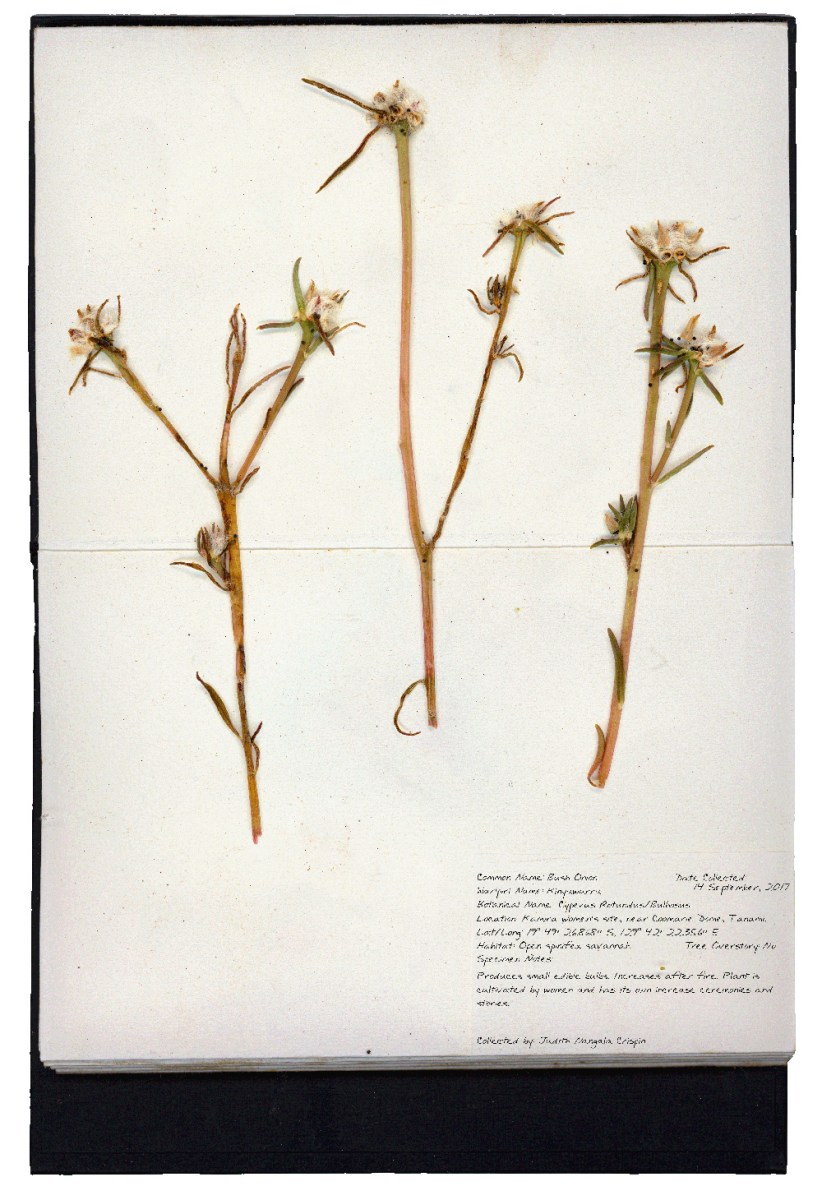

Plant pressing and annotated sky and land maps bejewel The Dingo’s Noctuary, along with her animal photographic portraits, cataloguing a love of the night sky, the living landscape and its inhabitants.

Appendices catalogue desert birds, a sort of glossary that details Nangala Crispin’s linguistic associations between constellations, planetary bodies and creatures of the land, as well as meticulous recordings of the location of impact craters, communities and cultural sites, mountains, mines and massacres.

There’s a sensitivity in her storytelling – poems she’s written, some at the request of her Warlpiri friends, that tell of murder, violence and loss. Nangala Crispin has been careful to respect the wishes of the Warlpiri, and those of the people whose stories she tells.

Beyond being a love letter to Country, The Dingo’s Noctuary is very much about the journey of a woman who is coming into the fullness of her own power.

Nangala Crispin’s friend Lily, a Warlpiri woman from Katherine in the Northern Territory who she writes about in the book, once told her that women raised in white society had forgotten where their power comes from. ‘Lily explained that being a woman is its own power,’ Nangala Crispin says. ‘The fact that we can bear children, the fact that we can have this empathy with other life forms.

‘And the fact that we can stare down birth and death without flinching.’

Getting up close to death

The animal photographic portraits that feature in The Dingo’s Noctuary came to be, in part, because Nangala Crispin wanted to be able to better understand death, so that when the time came for her to say goodbye to those she loves – which she writes about in her poetry – she was ready to play her part, without being overwhelmed by her own grief.

‘One of the things that the Walpiri women explained to me over many years is that the role of younger women is to be able to stand up strong at birth,’ says Nangala Crispin. ‘Then as you get older, you learn how to do the same thing at death, so that you can prepare bodies.’

‘Lily once said to me, you can’t learn how to be strong at death if you don’t know what death is, because death is a box disappearing behind a curtain in a crematorium.’

Nangala Crispin thought, ‘Well, I’ll start small. Snakes and birds and just learn what death is. Learn it, really learn it.’

Art as a collaboration with Country

In creating her art, Nangala Crispin was driven by her desire to distance herself from what she saw as a Western art canon that glorifies (a mostly male) artistic ego. ‘I wanted to know, is it possible to collaborate with Country on art, without me imposing my will over the top of it all?’

The idea emerged that she could use photographic paper to create a sort of collaborative self-portrait. ‘My role in it would almost be like a choreographer.

‘I place them on the page, and I cover them with a Perspex box, and then they begin to break down. The chemistry that comes out of that animal – they’re chemicals with terrible names like putrescine and cadaverine. Essentially, they’re kind of fats with minerals, which is not that dissimilar to photographic developer.’

She tries not to remove the animal from the place where it died, if she can help it, so the portraits of the animals begin with hours of exposure to natural light, sometimes a double exposure, using materials at hand, such as sticks, mud, blood and leaves, before she buries them near where the body was found.

‘It feels like one of life’s rituals instead of an art practice,’ she says.

Her process – ‘lumachrome glass printing’ is the term she’s coined – has been further developed by research into older photographic practices, as she’s sought out expertise from other artists, including Pierre Cordier, the late Belgian artist and pioneer of the Chemigram – a process of painting with photographic chemicals.

‘It was astonishing to me what happens as the animal begins to break down as the chemicals change. You can just learn so much just from looking at the images.’

Animal saints and god rays

Surrounded by stars and dense layered darkness, the animals in Nangala Crispin’s portraits appear as luminescent figures – the multiple exposures often giving them auras of saintly light. There’s something distinctly angelic about them – an effect of the exposure process that Nangala Crispin admits she doesn’t have a lot of control over, but she works to interpret it as it happens, intuiting their names and stories, worthy of divine beings.

In the case of Juliette – a stillborn gosling Nangala Crispin’s friend Victoria once brought her from her farm – the print very soon started resembling a sun, with rays shining from the central figure. ‘My friend Wanta Jampijinpa, he used to say to me that when the old people pass away, they’d become stars,’ she says. ‘And I was telling this to Victoria, saying this gosling is on his way to become a sun – because that was how the print was developing.’

Nangala Crispin leant into what was appearing on the paper, using vegemite and other household chemicals to create the clouds, and then cut the work into a circular shape to resemble a stained-glass window you’d find in a Cathedral or a Church, depicting the Christian God, or angels or saints.

‘There are so many things that annoy me about churches,’ she says, ‘but one of them is is that you go in there and all the saints are people. Like it’s not possible for any other being to manifest its divinity. And when I look around, I don’t see very many goslings that are perpetuating genocides or building nuclear weapons – that’s humans.

‘So why can’t we have saints that are wombats or rabbits or goslings?’

A portrait made in the smog of bushfire

On of the artworks in The Dingo’s Noctuary depicts a snake surrounded by constellations of stars. Zoe descends to comfort her daughters, in a burning country is a favourite of Nangala Crispin’s, because it was made when she had been out fighting the 2019–2020 Black Summer bushfires raging outside of Braidwood, New South Wales – with many other women volunteer firefighters like herself – and it tells a story of hope and of women’s resilience.

‘I found this little tiger snake that died from smoke inhalation, I assume, because it was otherwise perfect’ says Nangala Crispin.

Around that time, she had been reading the Gnostic story of Sophia from the Nag Hammadhi – an alternative to the biblical Garden of Eden story. Sophia, the feminine manifestation of divine wisdom, sent her daughter Zoe down in the rainclouds in the form a snake, to liberate Eve, where she had been imprisoned by the Demiurge.

‘I gave this snake the name Zoe,’ says Nangala Crispin. ‘I mapped out what all of the stars would look like that night on the other side of the smoke, because I couldn’t see them.

‘When you’re not living in the middle of the city, if the stars aren’t there, it feels like something’s very wrong with the world.’

Using seeds, and copper chloride to give the red giants their hue, she created the constellations, covering the snake and seeds with glass, and leaving them for weeks to develop through the light of the hazy sky.

‘It was sort of comforting looking at that print, knowing that those stars were on the other side of that smoke,’ Nangala Crispin says. ‘And in my mind, little Zoe would find her way back up, when the smoke cleared.’