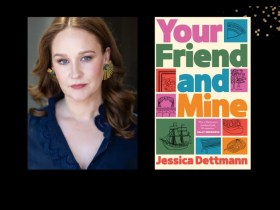

Part of the Taiwanese First Nations delegation at the Yirramboi international artists welcome party, 6 May 2019. Image: Pulima Art Festival.

In Australia, the history we are taught typically centres British legacies; even narratives that acknowledge the brutality of European colonisation seldom pay attention to other dynamics in the region.

‘The invaders may have been different, but essentially we’re under the structures of the same machine.’

But that is slowly changing in the arts. In 2019, Melbourne’s Yirramboi Festival includes several exciting cross-cultural collaborations between First Nations creatives across the world. Most notably, Yirramboi’s partnership with Pulima Art Festival in Taiwan continues to grow, this year bringing 13 Taiwanese Aboriginal artists to Melbourne.

Taiwan is a less obvious choice for collaboration than Aotearoa or Turtle Island (North America), which perhaps have more in common with Australia as lands colonised by European nations who established settler-colonial states. Taiwan’s tangled history sets it apart. ‘We’ve had waves of invaders from Holland, Spain, the Qing Dynasty, Japan, through to the current Taiwanese republican government. So it’s more complicated for us,’ said Watan Tusi of Taiwan’s TAI Body Theatre.

But Carly Sheppard, a local artist who is collaborating with Watan, feels there are still shared experiences. ‘The direction may have been different, or the invaders may have been different, but essentially we’re under the structures of the same machine. It’s just got a different face,’ Sheppard told ArtsHub.

From Taiwan to Melbourne

The Yirramboi X Pulima Art Festival partnership opened this year with a welcome party for the Taiwanese delegation in the gardens of the Meat Market in North Melbourne. In some ways, the event had the typical formalities of a diplomatic reception, with hors d’oeuvres, speeches from dignitaries, and gifts being exchanged. But there was also something very poignant about the circumstances of this meeting on stolen land.

Though N’arweet Carolyn Briggs, her daughter (and Yirramboi Creative Director) Caroline Martin, and grandson Jaeden Williams conducted the Welcome to Country and cleansing ceremony partly in Boonwurrung language, most of the speeches and conversations throughout the night took place in English and Mandarin – languages introduced by the colonisers. With 17 Aboriginal ethnic groups officially recognised in Taiwan, and hundreds of Indigenous language groups throughout Australia, it is necessary to use a lingua franca.

To add another layer of complexity, the exchange is supported by settler governments on both sides: the City of Melbourne and Taiwan’s Ministry of Culture. Australia does not have official diplomatic relations with Taiwan as it does not recognise the island republic as a country, though the government encourages ‘people-to-people’ connections.

Many of the artistic collaborations that have resulted from the partnership are indeed deeply personal.

‘This could be an entirely different thing if you were collaborating with a different Aboriginal Australian,’ Sheppard said of her collaboration with Truku artist Watan Tusi.

Brisbane-born Sheppard traces her roots to the Kurtjar people of the Gulf of Carpentaria, but she grew up in Melbourne.

‘If I wasn’t Carly – I didn’t grow up on my Country learning my dances; I don’t have anything traditional to share because that’s not the paradigm I exist in – but if they were to collaborate with someone else, it would be a completely different work and a completely different relationship,’ Sheppard said.

Carly Sheppard and Watan Tusi, 6 May 2019. Image: Jinghua Qian.

Though Sheppard and Watan have spent several months together over the last two years, this time Watan is in town for less than two weeks. There isn’t the space or time in these exchanges to show the full diversity of First Nations experiences within Australia or Taiwan, nor to communicate political and historical complexities to audiences who might lack context – and besides, Sheppard and Watan explain that that’s not really what they’re trying to do.

‘I don’t represent anybody except my own self and my own stories,’ Sheppard explained.

Making art work

As I speak to Sheppard and Watan in English and Mandarin and translate their answers to each other, I am struck by their creative process.

‘I love that there’s this massive language barrier,’ Sheppard said. ‘Watan and I rarely talk […] He makes, and I see, and then I make, and he sees, and we layer it.’

Watan explained: ‘Sometimes you can talk something to death.’

As dancers, the fact that the language barrier forces them to communicate with their bodies is a blessing.

Sheppard is presenting a double bill at Yirramboi: her new solo work, Negotiating Home, and her collaboration with TAI Body Theatre, Red Earth, a dystopian dance piece concerned with how humans are filling the world with waste.

‘Though we’re both Indigenous, our relationship to land, our perspective and knowledge and experience of land is very different,’ Watan explained. ‘So we looked for what we share, and we found a commonality that goes beyond First Peoples: the issue of waste and environmental destruction.’

Queer connections

Many of the artists participating in the exchange and Yirramboi generally are LGBTIQ, including Sheppard and Watan, and the ways in which queerness intersects with contemporary Indigenous identities is often part of their work.

‘This occurrence is a queer blak renaissance,’ writes Nayuka Gorrie (Kurnai/Gunai, Gunditjmara, Wiradjuri and Yorta Yorta) in the exhibition catalogue for insideOUT, Ngarigo artist Peter Waples-Crowe’s exhibition at Koorie Heritage Trust.

The exhibition involves collaboration with a number of artists including Truku performer Dondon Hounwn and blurs all sorts of binaries. Working across collage, painting, sculpture, textiles, video, animation and performance, Waples-Crowe’s work makes use of a wide range of found imagery and text such as early colonial etchings, newspaper clippings, and political slogans. ‘Are you a brotha or a sista?’ one image asks.

‘Each of these awkward collages maintains the ability to create moments of unsettling tension,’ said Myles Russell-Cook, Curator of Indigenous Art at the National Gallery of Victoria, in his speech at the launch. ‘They don’t sit right together – in the way Australia’s history doesn’t sit right.’

The exhibition launch, CampOUT, turned the gallery space into a party venue with a performance by Mojo Juju, DJ set by Natalie Smith of DJ ReCONciliation, and models with dingo make-up walking, prowling and prancing among us. Waples-Crowe uses the image of the dingo – his spirit animal – to challenge assumptions about authenticity and who deserves recognition.

Wallpaper at the venue declares: ‘Gay Aboriginal men are real Aboriginal men.’

Artist Peter Waples-Crowe with singer Mojo Juju at insideOUT exhibition launch, 4 May 2019. Image: Myaree Iluka via Koorie Heritage Trust.

Carrying the past into the future

Yirramboi means ‘tomorrow’ in the shared local languages of the Boonwurrung and Woiwurrung peoples. A common thread through many of the works in the festival is an engagement with how culture transmits and transmutes through time.

Watan spoke of how he took up weaving, though it is traditionally a women’s practice in his Truku culture. Eventually, his own tribe came to accept him as a weaver, but others resisted. Some elder women expressed that they were happy to see someone willing to learn, though they weren’t willing to teach him. Another participating Truku artist, Labay Eyong, quipped that in in the past women wove clothing, but now she weaves a giant red dinosaur.

At the welcome party, performers in woven and embroidered garments playing mouth harps and other traditional instruments were followed by figures in long black braids and neon body paint, writhing to thumping electronic music under a lime green net. Like Waples-Crowe’s art, this work challenges assumptions about how an Aboriginal person should look or hold their body, or what kind of art First Nations people might make. This seems particularly salient for an international exchange on the lands of the Kulin Nations, as didgeridoos and dot paintings remain the most recognisable images of Aboriginal Australian art overseas, though they are not part of the traditions of south-eastern Australia.

When it comes to the future, Watan suggests that shapeshifting is nothing new: ‘Our old people have three names – their Aboriginal name, Chinese name, and Japanese name – three names in just a few decades. So they have sharpened their survival tactics.’

Yirramboi Festival runs until 12 May 2019 at various locations across Melbourne, on the land of the Boonwurrung and Woiwurrung people of the Kulin Nations. View all the events in the Yirramboi x Pulima program.