I first read Moby-Dick because I thought I should. I knew it would be a 215,000-word dose of literary castor oil, but I’d feel better afterwards.

I can’t exactly remember when that was, but I know for certain that I finished reading it in Darwin. I hadn’t intended to take Herman Melville’s classic on a northern holiday, but I was enjoying it so much I didn’t want to leave it home.

This is the thing not enough people tell you about Moby-Dick, a book commonly regarded as difficult: it is entertaining. It is also profound, confounding, hilarious, queer, exasperating, encyclopaedic. What I like best is that it remains mysterious, permitting every reader at every new reading to develop their own thoughts on what the book is about.

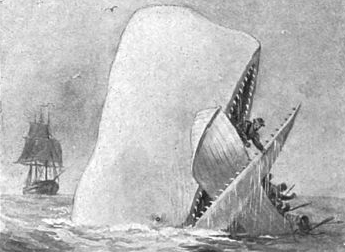

If plot is your concern, here it is in one sentence: an obsessed sea captain pursues a white whale which ultimately kills him. I would apologise for the spoiler, except that there is no novel in which plot is less important. What matters is the language, the jokes, the philosophising.

Moby-Dick: ‘a strange sort of book’

In May 1850, Melville wrote to his friend Richard Henry Dana, encapsulating so much of what makes the novel exceptional: ‘I am half way in the work … It will be a strange sort of book, tho’, I fear; blubber is blubber you know; tho’ you might get oil out of it, the poetry runs as hard as sap from a frozen maple tree; — and to cook the thing up, one must needs throw in a little fancy, which from the nature of the thing, must be ungainly as the gambols of the whales themselves. Yet I mean to give the truth of the thing, spite of this.’

In 2026 I am taking a measured approach to rereading Moby-Dick, flinging my harpoon at one chapter per day. This means being present for the exciting parts when the Pequod is in frantic pursuit of the albino leviathan, but also being there for the mundane portions – the ropework, the rough shipboard carpentry, the processing of whale flesh.

Moby-Dick: endless invention

I marvel at the way Melville seems to invent ways to tell his story as he goes along. When he can’t find the right words for the task, he makes up new ones. When the straightforward narrative approach starts to flag, he changes it up with a song, theatrical dialogue, a catalogue of items of interest or a sequence of asides as if whispered behind a hand.

Toss in some Shakespearean stage directions and lengthy scientific expositions. The pace of the novel swells into something swashbuckling and urgent, then he puts out the drag-anchor and muses awhile about the meaning of whiteness. Consistency and tempo be damned.

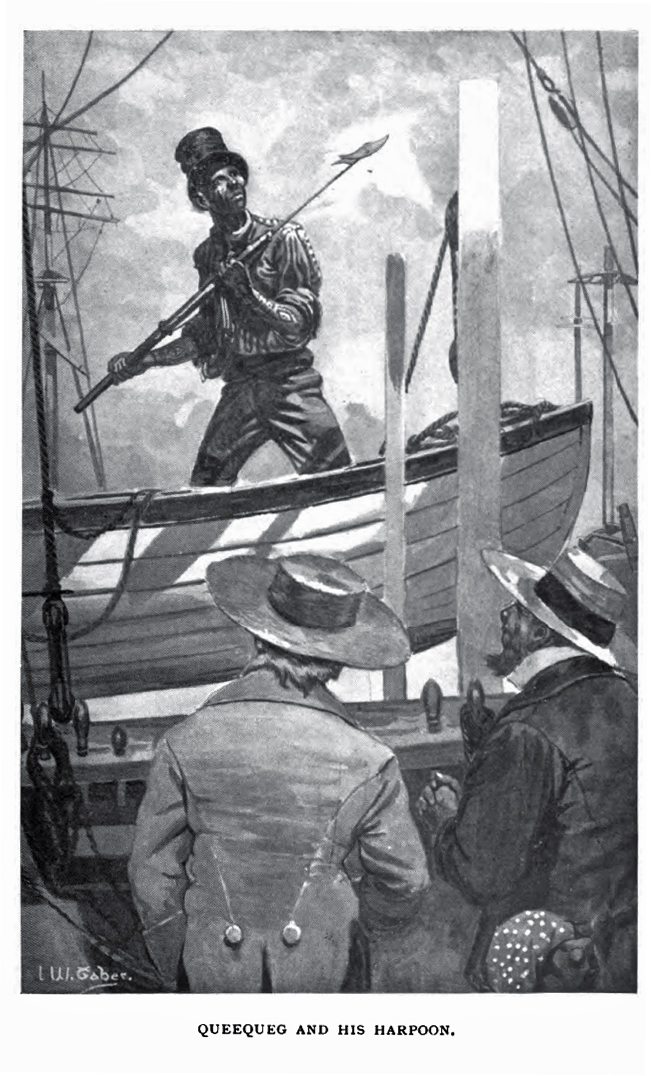

He has characters called Queequeg, Daggoo, Starbuck, Bildad, Tashtego, Boomer, and when he decides to name a fictious author, he comes up with ‘Fitz Swackhammer’. A century before Thomas Pynchon, Melville was Pynchoning.

And then of course there is Chapter 94, ‘A squeeze of the hand’. Readers, lulled by descriptions of shipboard cleaning tasks and arcane cetology are jerked (yes) to attention by one of the great homoerotic scenes in English-language literature. This chapter has been debated by scholars and sniggered at by students for 175 years. In a book with several fart jokes it is conceivable that he is playing it for laughs, but it could also demonstrate deep sexual longing. Whatever Melville was doing, this chapter is one more fascination.

For about a decade I made regular visits to central Australia. Despite its weight, I usually took Moby-Dick with me as a vade mecum. Reading it in the desert as temperatures crested 45 degrees was a wild trip. Lines like this hit differently: ‘To the last I grapple with thee; from hell’s heart I stab at thee; for hate’s sake I spit my last breath at thee!’

Moby-Dick: a book to grow with you

You can’t step into the same river twice. Similarly, each time you reencounter a book, you are a different reader. The best books seem to grow with you.

What surprises await me on this year’s rereading? Perhaps I will find greater empathy for Ahab, a man sometimes described as evil, and admire him more for confronting his foe after having his leg bitten off. Perhaps I will see refracted more insights into obsession and madness. Perhaps I will take guidance from Melville’s fascination with signs and omens.

The first time I read the novel, as a younger person with hotter blood in my veins, I identified with Ahab. Now I identify more with the whale. They are both scarred, carrying permanent injuries, capable of deep anger, but while Ahab manically pursues his quarry, Moby Dick seeks to be left alone.

Or maybe through this year’s slow reading I will let myself wallow in the magic and majesty of prose like this:

‘All that most maddens and torments; all that stirs up the lees of things; all truth with malice in it; all that cracks the sinews and cakes the brain; all the subtle demonisms of life and thought; all evil, to crazy Ahab, were visibly personified, and made practically assailable in Moby Dick. He piled upon the whale’s white hump the sum of all the general rage and hate felt by his whole race from Adam down; and then, as if his chest had been a mortar, he burst his hot heart’s shell upon it.’