Image via favim.com

Art can be bought and sold, mass-produced and exploited, but much that is best in art and culture is so self-evidently non-monetary that it is obvious even to lay people that it can’t be judged by the same yardstick as property values, stock options or commodity prices.

By their nature, their history and their example, the arts stand in colourful protest against the dominance of market forces (even if they provide lively instances of market activity); they are living proof of a higher good that makes policymakers, not to mention politicians, distinctly uncomfortable.

Artists are a motley crew at the best of times, but it is also true that they harbour few illusions about the mathematical inevitability of Pareto efficiency. Worse, they are often hostile to the interests of capital, even while demanding patronage. Such ‘vicious ingratitude’, as Turnbull said of the artists boycotting the 2014 Sydney Biennale, outrages the captains of industry and well-heeled scions of inherited fortune who dominate the board rooms of ASX 200 companies.

So what is the way forward? It turns out there are some rather good arguments for public support for the arts that need not slide into cultural elitism on the one hand, or special pleading and magical thinking on the other. In fact, the arts do have value, as the immense amount of enjoyment that they give millions of ordinary citizens every day shows.

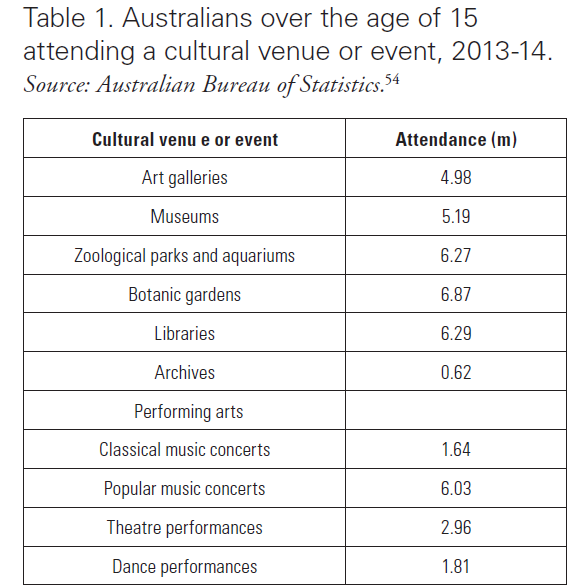

The argument is scarcely new—Aristotle articulated it 2,500 years ago—but in the current intellectual zeitgeist it is a newly radical proposition. The Australian Bureau of Statistics has collected fascinating data that makes this point. In 2013–14, 15.9 million Australians aged over the age of 15 attended a cultural venue or event—or 86 per cent of all Australians in that age bracket.

Table 1 below sets out some of the ABS data.

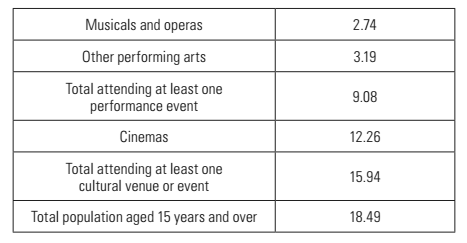

Of course, not everyone who turns up to a cultural event enjoys themselves. But millions do. The participation figures for culture in this country are striking, and deserve special examination. They show that around a quarter of all Australians make art or engage in artistic creativity. According to the Bureau’s long-running survey, ‘participation in selected cultural activities’, nearly five million Australians in 2013–14 spent time participating in the ‘performing arts, singing or playing a musical instrument, dancing, writing, visual art activities and craft activities.’

Australians also like making and supporting the arts: in 2006, Australian volunteered 30.6 million hours in arts and heritage organisations; another ABS survey in 2010 found that some 410,000 Australians volunteered for cultural organisations.

When you examine these statistics, the surprisingly widespread devotion of ordinary Australians to cultural pursuits comes into focus. Far more Australians engage in culture than engage in politics. More Australians make art or culture than play organised sport. More Australians attend an art gallery annually than attend a football game. And yet, the crude stereotype remains of the arts as a marginal, disreputable and even pathetic activity. The truth is the polar opposite: that engagement with culture is one of the foundation stones of Australian civic life.

This argument sometimes goes by the name ‘public value.’ While there is plenty of formal academic theory carried out under that banner, the phrase is useful for our purposes because it reminds us that culture happens in the public sphere. This, then, provides one powerful potential argument for state support of culture: the democratic value of cultural participation.

The fact that the majority of the citizens of the Australian State share a vivid and rich cultural involvement, means that culture is not some way-station on the road to the good life. It is the good life, a vision of a modern society where much of the meaning and value derived by individuals and families is expressed through cultural and artistic participation and creation. As John Holden put it, back in 2006, a policy that supports publicly-funded culture can be one in which ‘culture is seen as an integral and essential part of civil society.’

This is a vision in which the state supports culture because it enriches civic, social and public values, and because it is central to who we are as modern Australians. It is a vision that is democratic and collective, because it enriches not merely separate individuals, but the common good. It is a vision for culture that shares much of what is valuable in other domains of the human spirit: in religion, in education, and in the humanities.

As the British political scientist Adam Roberts pointed out in 2010, these activities ‘explore what it means to be human: the words, ideas, narratives and the art and artefacts that help us make sense of our lives and the world we live in; how we have created it and are created by it.’

This article is an extract from the Platform Paper When the Goal Posts Move: Patronage, Power and Resistance in Australian Cultural Policy 2013–16 by Ben Eltham published by Currency House today. Eltham. Lawyer and 3RRR presenter Michelle Bennett, and independent artist David Pledger will launch the paper at an open event at 6pm on 8 August at Collingwood Arts Precinct. Bookings essential.