Recent research shows that female directors are still severely underrepresented in Australia’s film, television and performing arts industry. In a panel talk at Sydney’s NIDA, veteran director Gillian Armstrong and rising talent Pearl Tan sat down with Margaret Pomeranz to talk about the myths of male genius and leadership, and how risk-averse investors and Australian review culture perpetuates those old ideas.

‘In Australia, only 17 per cent of film directors are women, about 21 to 22 per cent of TV directors, and only 10 per cent of the people directing commercials are women,’ said Armstrong. ‘When you know that the talent coming out of film schools is 50-50, then there’s something really wrong.’

Their suggestions ranged across policy reform and industry-led quotas, as well as targeted initiatives to help female directors survive the first tough years after film school.

The first four years

Armstrong is a vocal advocate for women in the film and television industry. Her research has pinpointed the time when the balance shifts. ‘The thing that was so shocking and so sad was that the gap is in the first four years that people leave film school. The girls are not getting their foot in the door and the boys are.’

She adds: ‘If you don’t get a break in those first four years, you can’t pay the rent … Apart from being completely broke and having to find some other way to make money, you start losing confidence in your own talent.’

Data helps but keep quotas simple

Armstrong is convinced that research and industry targets do shift attitudes. ‘That’s what it’s actually about. It’s called unconscious bias. The only way you can fight unconscious bias is to make it conscious,’ she said.

Tan, who sits on Screen Australia’s Gender Matters taskforce and is doing a PhD on intersectional characters, strongly believed in quotas as a way to break the ‘vicious cycle’. She said the taskforce had recently changed its targets, switching to ‘pure head counts’ rather than percentages to make them easier for industry to understand.

Carrots not sticks

Armstrong pointed to the successful Free The Bid initiative in the United States, which encouraged advertising agencies to seek out the reels of female directors. In Australia, she said there have been two highly successful schemes run by the Director’s Guild. One paid agencies to offer practical mentorships. Another handled the risk factor in a different way by paying the salary of a shadow director, who could step in if the junior director needed help. The results have been impressive, she said.

The effect of this work is cumulative, proving that female directors are not a commercial risk. ‘Every woman that makes a successful film does help others,’ said Armstrong.

She also encouraged early career directors to be aware of and engage themselves in policy debates—particularly around arts funding, Australian content controls, and the impact of content providers like Netflix on local drama production.

Make the best possible work

Surviving the early years after film school is also a matter of hard work. ‘Make something small and brilliant – stand out from the crowd,’ advised Armstrong. ‘Truly, it’s about your talent.’

She encouraged directors to be selective about their projects. ‘You’ve got to care about it too, the story,’ she said. Because without that passion, it’s not worth doing.

Do your homework

‘It’s a very difficult craft and art, and you only learn by doing,’ said Armstrong. Those worried about not being good enough need to come to terms with the fact that some fear is normal – a point echoed by Margaret Pomeranz. Fear ‘is a factor all through your career,’ she said. ‘When really great directors lose that fear of failure, their work drops off.’

Tan encouraged young directors to drop the imposter syndrome and to ‘accept that, if I get through the door … I’m just going to own it. I try to teach my students you’ve got to just go for it. Who cares why, you do deserve it.’

Creative confidence comes with time and practice. Armstrong advised: ‘Do your homework. Know what you want.’ When the big opportunity comes, you’ll be ready.

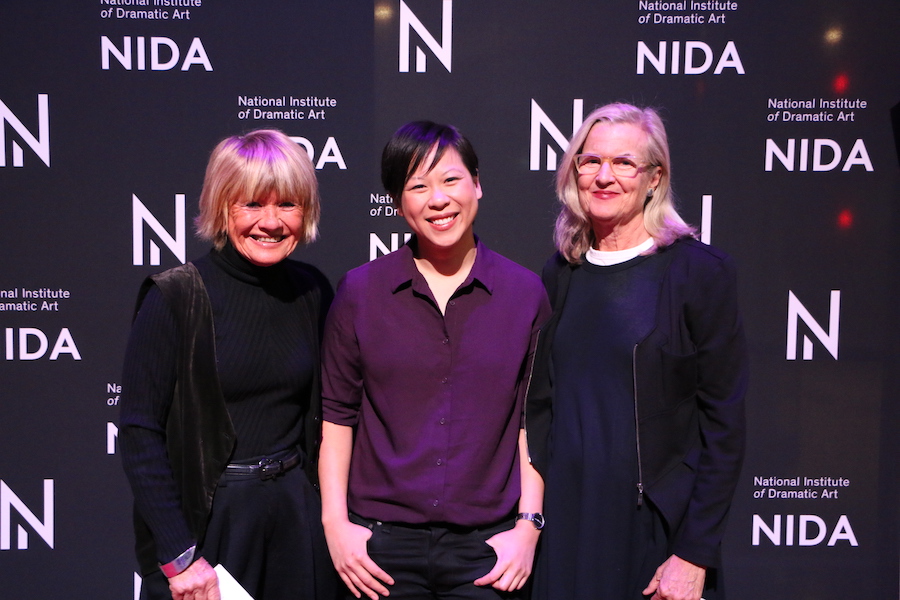

Margaret Pomeranz, Pearl Tan and Gillian Armstrong. Image courtesy NIDA Allison Tyra.

Find your people

‘You’re not a director on your own,’ said Armstrong. ‘Know what your strengths are. You can’t possibly be good at everything.’

Pomeranz agreed that learning to trust others was essential to success. ‘Ok, so you build up confidence—and you build up confidence enough to be able to trust other people. That was the most important thing that I learned…I started trusting people and it was the best thing I ever did’

Tan said there are now plenty of opportunities for young directors to ‘find your people’ including script-reading sessions at the Director’s Guild. Armstrong also encouraged directors to attend as many events as they can and ‘enter everything’ to get their work out there.

Armstrong added: ‘Never forget to trust your gut instinct – and get the best possible crew and the best possible cast.’

Be yourself

‘It’s only the media that think directors shout and yell,’ said Armstrong. Tan said there were outdated ideas about the typical traits of a leader. These tropes might prompt some women to ‘self-select out’ of the industry, but she suspected this happens well before film school. Neither believed there was any need for female directors to try to be loud or put on an act to succeed.

Being a genuine human being is also important. ‘The first thing I learned was, at the end of the day, to say thank you to my whole crew,’ said Armstrong.

Rest hard

Armstrong believed women still have to work harder than men to prove themselves, and were offered fewer breaks if they made mistakes. She cautioned female directors not to push themselves so hard that, for example, they give up on a last take or make compromises because they’re exhausted. In practice, that can be something as simple as sitting down on set whenever it’s possible.

Tan also suggested building recovery into work habits to avoid physical and creative burnout. Her own personal mantra is ‘work hard, play hard, rest hard’.

Open the gate

‘The challenges are magnified for people with more than one marginalised identity,’ said Tan.

Talking about the finding that only 17 per cent of film directors are women, she added: ‘How many of those were more diverse, even? Disability? Queer? From people of colour? Are we even considering that in this conversation? How do we consider that when we can’t even get more than 17 per cent women at the moment?’

Tan argued that women have a responsibility to make sure others are not oppressed in the same way they have been, or systemic patterns of inequality will only continue. ‘It’s our responsibility to reach out the hand.’

This article is based on the NIDA panel, Getting a Share of the Chair: Women Directors in Film and Theatre.