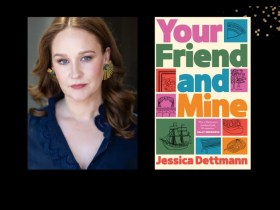

Artistic Director Jodee Mundy’s Imagined Touch, 2016. Photo by Jeff Busby.

The aesthetic use of access in art, particularly in theatre-based productions, is becoming a prominent and exciting principle that underlines marginalised artists’ creative practice.

By devising artistic projects with access in mind from the very beginning, the aesthetics of the artwork is changed in a unique and intrinsic way – elevating audience experience, and altering the way stories are told.

In many examples, stories told with access at the forefront creates work that all people can enjoy, and is not aimed specifically at able-bodied audiences.

However, in the example of award winning art performance Imagined Touch, devised by artist Jodee Mundy in collaboration with two Deafblind artists, performer Heather Lawson and pianist Michelle Stevens, the work targets able-bodied audiences.

A multi-sensory arts performance project exploring the world of Deafblind culture, Imagined Touch, first conceived in 2013, exposes able-bodied audiences to tactile sign language and the navigation of the world through this unique point of view.

‘When the abled-bodied audience enters the space they are given head-sets and goggles so they don’t see or hear,’ Mundy told ArtsHub.

‘Deaf people experience the work but they are the ones guiding able-bodied people. And then, for people who are blind or visually-impaired, we give them an audio description of everything that’s going on.

‘So in this work everyone plays a different role – and we shift the power dynamic. What I love about that is suddenly it’s the people with disability who are the ones telling the story and people who are able-bodied are receiving.

‘In essence what we were doing is revealing our culture, our language and our rituals – how we see the world. I think it’s important to point out that able-bodied culture is about exclusion, and disabled culture is about inclusion. So, I think for so many years, centuries, people have just seen disability as other or less,’ she said.

After massive success in Australia, Imagined Touch will travel to the Barbican Centre in London in November later this year to continue the cultural exchange. Mundy’s new work Personal, now touring regionally, is another stellar example of access creating a new aesthetic, where the principal underlying the work is this focus on accessibility.

Read: Review Personal at Art House

‘What I really like about the aesthetic use of access is when you can have different members of the audience experience the same work in a different way,’ said Mundy.

Layers of access

David Doyle, Executive Director of DADAA said to ArtsHub: ‘It’s about creating other layers of access for both the story teller and the audience. It’s building that multi-dimensional access for audiences. So for the performer or storyteller to build different layers in their narratives.’

DADAA, located across Western Australia, provides access to arts and culture for people living with disability. Now in its third year of a four year partnership with Perth Festival, DADAA produced and presented Julia Hales’ You Know We Belong Together earlier this year, also in partnership with Black Swan State Theatre Company.

Read: Review You Know We Belong Together

You Know We Belong Together co-created by Hales’ tells her deeply personal story through video, dance and song. Documentary style films are projected onto the stage giving the show a multi-layered perspective.

Doyle said, ‘I think as a society we are so used to consuming digital in particular that it is a very simple mechanism for us to relay information – in Julia’s case it allowed for people who have had other experiences with lived disability, for example the mum, Hermoine Merry, in the play who has a child with Down Syndrome – it talks about the pressure to terminate her child.

‘So it provided really good links that reinforced what Julia was saying. The mechanisms used really extended the conversation beyond Julia … bringing another layer of politics into the work that we don’t really talk about in our day-to-day lives as Australians.’

Doyle also mentioned the way we create art is changing due partially to the National Disability Insurance Scheme (NDIS). He looks forward to the cultural changes that will be ushered in by the Scheme.

‘I am extremely happy that this is happening at the same time as the NDIS rolls out across Australia. Australians with a disability are for the first time emancipated in that they have the resources in their pocket. They have choices in the decisions they want to make over their lives. I’m very happy that this partnership with Black Swan and Perth Festival is happening at the same time as the NDIS is rolling out,’ he said.

‘It’s showing what the NDIS can do. The NDIS is the quiet partner in this as Julia is an NDIS funding recipient and she used her NDIS funds to contribute to the production of this work, and the whole creative development. It’s Julia deciding that yes, this is my goal, I want to do this and I want to put my resources there – the arts.’

Access into the future

Doyle reflected, ‘I think ultimately disability becomes part of our broader cultural narrative. It’s starting to make disability part of normal human experience. We will all experience disability at some point in our lives. And it’s removing that otherness, but also privileging that very unique cultural experience that a person with a disability has to take on the world, to take on relationships, to take on Australia.’

Mundy explained that artmaking with all people in mind is ultimately about inclusiveness. ‘Yes, it’s art, but it’s about feeling and inspiring and beauty,’ she said.

‘It’s also about asking, “What’s our point of difference?” We are actually about including people, and the more audiences that see that will have a taste of what it means to be inclusive. And how it’s such a beautiful culture, and it’s not just about access – it’s actually about participating and connecting with people, and having everyone at the table.’

Mundy said, ‘I have this thing that I say: access is walking through the door, inclusion is sitting at the table, eating the food and talking about it. The work I make is participation, but it uses access and inclusion modes – then to flip that into something we can’t imagine.

‘So that’s what I love. And you know when I think of the future, with hologram interpreters and swipe screens. Where we are building into – where you go into a museum and people who are blind can immediately walk into an immersive sound world, and people who are able-bodied can use them too. It’s something that is artistic, it’s not just “Oh here you go – audio descriptions”. It’s something that is integrated, it’s sexy, it’s cool – it’s Star Trek,’ she said.

‘We have flown someone up to the bloody moon and back and we find it hard to get a personal wheelchair up to the second floor of a building. Anything is possible and that’s where I sit, in the future.’

Jodee Mundy’s Personal is touring regionally, learn more at: jodeemundy.com

Keep up-to-date with DADAA at: dadaa.org.au