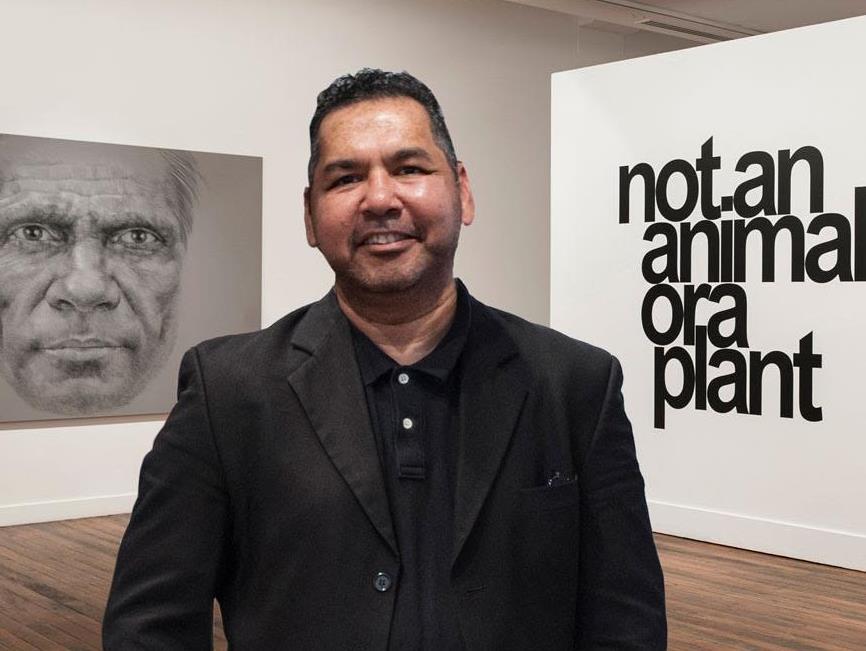

Vernon Ah Kee with his NAS Gallery survey exhibition, Not an Animal or a Plant; image courtesy the artist and NAS Gallery, photo by Peter Morgan.

A story about growing up in a tourist town in regional Queensland delivered an astoundingly real message and left an auditorium full of museum and gallery professionals silent at last month’s Public Galleries Summit 2018.

I am referring to artist Vernon Ah Kee’s account of Cairns in the 1980s, one he demonstrated has changed little when it comes to inclusive practice and cultural respect.

Ah Kee’s artworks move between text works with hard-hitting racial slogans and large-scale drawings of his ancestors – both which speak about his understanding of his place in the world.

Read: Vernon Ah Kee: Not an animal or a plant

His works have been exhibited at the 2009 Venice Biennale, the 14th Istanbul Biennial (2015) and the 1st International Quinquennial of New Indigenous Art at the National Gallery of Canada, Ottawa (2013). And yet it was only last year (January 2017) that his work was recognised with a major solo exhibition in his own country.

It reinforces Ah Kee’s message to the sector: that it has played the race and gatekeeper card too long. ‘What if I was white; seeing galleries and museums through the lens of Aborigines? I have questions,’ he said at the Summit .

Blackfellas should run galleries

‘I think blackfellas should run galleries … all of them. We could give a special place to whitefellas – maybe one gallery – and I reckon the way to give a space to whitefellas is you all talk amongst yourselves, form a committee and come up with some really good ideas about what would make a good space for white people, and then you present it to us. And if we don’t like any of them options, then bad luck.’

Playing the role of provocateur among his professional colleagues, Ah Kee’s comment – while partially in jest – was a wake-up call and a harsh reality long overdue in its reckoning.

Ah Kee grew up in the 1980s, ‘at a time when Aboriginal art really exploded through the tourist market’, and first gained traction in tourist towns like Cairns.

‘Cairns had a couple of commercial galleries. Now it has none. Now every show space in Cairns is driven by the tourist dollar and geared towards it,’ he explained.

While Cairns has a fairly significant regional gallery, which Ah Kee frequented as a high school student, he did not recall the gallery ever employing an Aboriginal curator, particularly his people – the local Yidinji people. Nor did the gallery have Yidinji programing.

‘The other reason Aborigines don’t access the Cairns gallery is that they charge an entry fee – you are charging people who already have no money to go into something they’re not interested in. What’s wrong with this picture? When you expand your audience you want to expand to people who aren’t interested in art and encourage them to come in,’ Ah Kee said.

The gallery has plans to expand and has identified the former Court House and Magistrate’s Building as the ideal location, however Ah Kee pointed out that the choice is flawed and lacked consultation.

‘When I say that the race card is already in play is we know that the legal system is geared towards favouring white outcomes. The population of Aborigines incarcerated is proof enough. So whoever it was who decided in their wisdom to pick the Court House – nice colonial building, colonial country with colonial history – this building channels that position,’ explained Ah Kee.

He continued: ‘So how do Aborigines access that space? They don’t. What you have is really good example of racism and gatekeeping.’

Read: How we can hand our public institutions over to others

Ah Kee was clear that it was not an issue he had with the gallery or the people who work there, but that it was a structural and historic one, and is indicative of the way galleries exist and function in this county.

It is a lesson for the entire sector to consider, and the room was listening, judging from the receptive response among delegates at the Public Galleries Summit.

We need to change the way we talk about Aboriginal art

Ah Kee believes we are caught in a kind of time warp when it comes to talking about, and presenting, the work of Indigenous artists.

On reading a review of the 21st Biennale of Sydney, Ah Kee made note of a comment by a senior Sydney writer and curator with regard to the work of George Tjungurrayi at Carriageworks.

‘She says that some of them are hung on their side to give another view of the landscape. And I thought, really? Now forgive me if I’m wrong but that is the way Aboriginal art was described 40 years ago. Whether by coincidence or design it was also how it was described 35 years ago, 30 years ago, 25 years, five years ago and I could be wrong but I am betting there will be Aboriginal art in the Sydney Biennale in 20 years time and the descriptors for it will be the same.

‘What is the reason for that? I think there are no blackfellas in institutions. If there were, we would have descriptors for George Tjungurrayi that would describe his life, like the way people describe white artists, who have individuality thrust upon them,’ he said.

Currently, George Tjungurrayi’s career might well be the same as Rover Thomas’ because we use the same descriptors as if they lived the same lives, they lived in the same house, and their careers were spent siting around the same fire, said Ah Kee.

Whether the art is good is apparently neither here nor there. The fact that the Australian art industry appropriates the popularity of Aboriginal art to field everything else – and this is reflected in our galleries – means there will never be understanding or true representation, explained Ah Kee.

He warned that this is a much bigger question about Australia deciding how the world sees us.

‘If we really want the world to see us differently, we need to have Aboriginal people in these spaces making critical decisions because then we would know what men like George Tjungurrayi think of the spaces, think of the market, think of the world outside of Australian art and there would be no need to hang his paintings sideways to get a different idea – you could ask the man himself.

‘I would hope not, but I would bet that this race card is never going to be picked up off the floor,’ Ah Kee concluded.

The Public Galleries Summit 2018 was held at Carriageworks and was organised by the Museums and Galleries of NSW and Regional and Public Galleries Association of NSW.