Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people are advised that the following review contains the names of deceased persons.

Some exhibitions are pretty much review proof, and Blak In-Justice: Incarceration and Resilience is certainly a case in point. Curated by Kent Morris, Barkindji artist, curator and Creative Director of The Torch, the exhibition is the very definition of small but mighty. Spread across a few rooms in Heide, Blak In-Justice is a deep dive into the realities of Indigenous incarceration and deaths in custody in Australia – as interrogated and spotlit in the works of a range of First Nations artists – some very well-known, others less familiar.

The statistics they’re responding to are familiar, but never less than shocking. And they’re worth repeating here:

Less than 4% of the Australian population yet represent 33% of the national adult prison population. Indigenous men are 17 times more likely to go to prison than non-Indigenous men and First Nations women are 27 times more likely to go to prison than non-Indigenous women. Since the Royal Commission into Aboriginal Deaths in Custody in 1991, incarceration rates for Indigenous Australians have more than doubled and deaths in custody have continued to increase. Of all young people in detention, 65% are First Nations, who only make up 6.6% of the Australian population aged 10–17.

There have been manifold artwork responses to these issues over the years, but gathered together in this careful curation from Morris, the impact is immense.

Among those artists represented are pivotal names like Destiny Deacon, Gordon Bennett, Trevor Nickolls, Karla Dickens and Richard Bell, alongside a number of acclaimed artists who have come through Morris’ Torch program, such as Palawa artist Thelma Beeton and Taungurung/Boonwurrung artist Stacey Edwards, two women who found each other during their period of incarceration and were able to work together and support each other both in and out of prison.

Read: Exhibition review: Wedgwood: Artists and Industry, Perc Tucker Regional Gallery

The pair met and forged a friendship in the Dame Phyllis Frost Centre and have since shared exhibitions and undertaken a joint residency at Boyd Studios. A selection comprising 12 smaller pieces shows how Beeton’s bold and colourful emu works sit in perfect harmony with Edwards’ geometric backgrounds and Australian fauna.

Some of the works were made by artists during periods of incarceration and their subject matter may not necessarily reflect this directly, while other works depict the realities of prison life or critique the failings of the country’s justice system head-on.

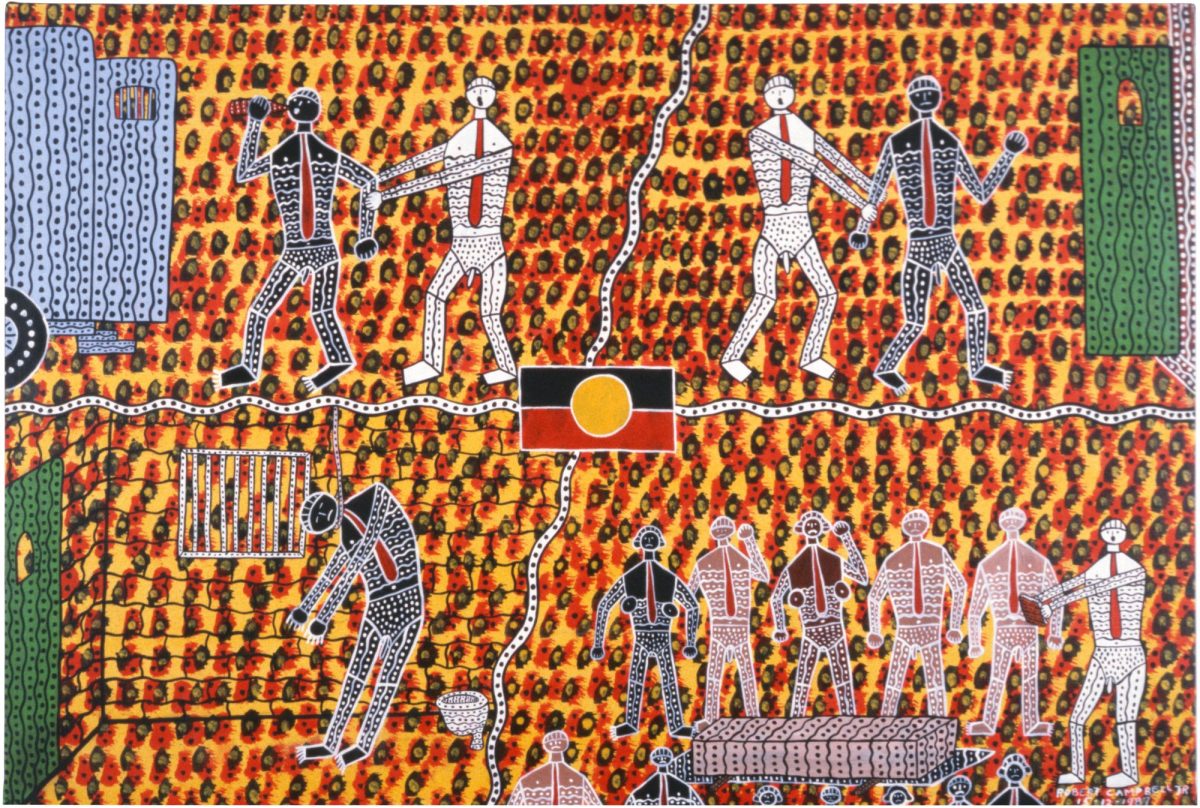

None do this more succinctly and eloquently than Robert Campbell Jnr’s Death in Custody, a single painting comprising four panels tracing a First Nations prisoner’s journey into a paddy wagon, into a prison, into a lone cell and, finally, into a coffin. It’s a confronting and heartbreaking image.

Morris has also been able to secure famous works like Gordon Syron’s brilliant and potent Judged by his Peers, a painting that shows the rank hypocrisy of a system that claims impartiality, when in reality a First Nations defendant like Syron was judged not by his actual peers, but by an all-white jury. In the simplest way imaginable, his painting flips this on its head by presenting the image of a white defendant standing in the dock surrounded by Black faces – in the witness box, around the lawyers’ table, in the jury box and in the judge’s chair.

Blak In-Justice: Incarceration and Resilience is at Heide Museum of Modern Art until 20 July 2025; ticketed.