At the Odyssey Literary Festival, four Australian authors of young adult (YA) fiction discussed hope and optimism in what looks increasingly like the End of Days.

The panel Reads Like Teen Spirit: Writing Readers Through Trying Times looked at how YA writing tackles hard issues from consent to climate change. Danielle Binks, literary agent and author of the forthcoming novel The Year the Maps Changed moderated the discussion, which featured authors Nina Kenwood, Alison Evans, and Astrid Scholte.

Not all YA readers are, in fact, teenagers – Binks pointed out that research has found that 55 percent of YA readers in the US are adults, with the age 30 to 44 market accounting for 28 percent of sales. Nonetheless, writers have to focus on their target audience of young readers, and that comes with a certain sense of responsibility.

Visibility and representation

Many YA writers hope to create or reflect more expansive worlds and characters than they saw represented when they were children or young adults themselves.

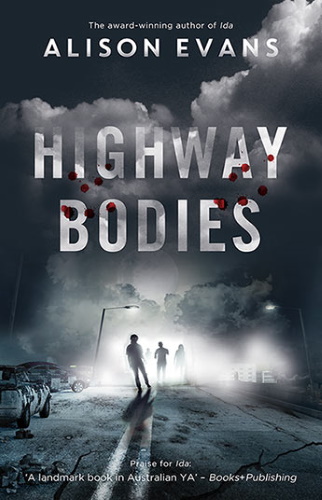

Evans commented that as a non-binary author, they write in part with their own teenage self in mind. Their second novel, Highway Bodies, is a zombie apocalypse story with a cast of teens, many of whom are queer. There’s ‘healing and power’ in portraying these underrepresented narratives, Evans explained – it’s an honour to be able to interrupt the loneliness that so many LGBTIQ teenagers feel.

Scholte, too, spoke of challenging gender tropes in her fantasy bestseller Four Dead Queens, which is set in a monarchy ruled by four women.

But narrative and characterisation can suffer if you take a tick-the-box approach to representation – whether in terms of characters or contemporary issues. A moralistic message loses authenticity, Kenwood said, but often representation comes through organically when you focus on making a character real.

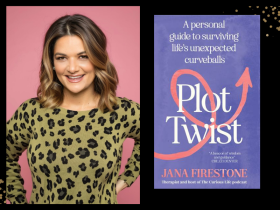

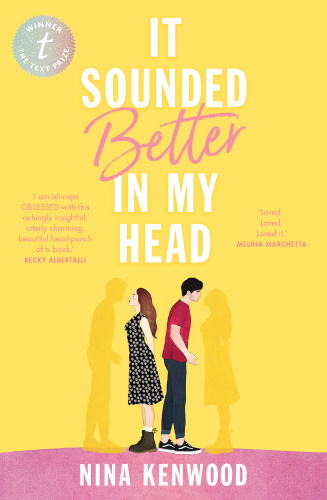

It Sounded Better in my Head by Nina Kenwood and Highway Bodies by Alison Evans. Cover images supplied.

Consent, sexuality and gender

Kenwood’s debut, 2018 Text Prize winner It Sounded Better in My Head, is a YA romance that touches on consent and communication.

‘I didn’t set out to write about consent,’ Kenwood explained. Rather, the topic emerged through the narrative’s focus on the beginning of a relationship, and all the emotional and sexual negotiation that comes with that.

Sexuality and gender have long been an important feature in YA literature. Binks pointed to Judy Blume’s beloved 1975 novel, Forever, which Blume wrote for her daughter because there were so few stories in which teenagers had sex without being punished for it.

‘Girls in these books had no sexual feelings and boys had no feelings other than sexual,’ Blume explained on her website. ‘Neither took responsibility for their actions. I wanted to present another kind of story.’

Fantasy and escapism

Evans also presents ‘another kind of story’ by writing trans and gender diverse characters into the landscape of rural and regional Australia. In one story, they portray a trans girl in country Victoria who has an easy time transitioning. ‘Is this realistic?’ the author’s partner asked – perhaps not, Evans conceded, but they suggest that this optimism is necessary: portraying this positive experience makes it possible.

While Kenwood’s novel has a contemporary setting, Evans and Scholte work with speculative and paranormal themes. Whether utopian, dystopian, or a bit of both, genre fiction enables writers to dig deep into alternative futures. Many of the biggest bestsellers in YA fiction over the last couple of decades have been science fiction or fantasy – just look at the Harry Potter, Hunger Games, and Twilight multi-format franchises.

Read: Why escaping reality is good for kids

Reflecting on their own teenage tastes, Evans explained that the attraction of genre fiction often lay in the young characters having more freedom and being ‘less parented’ than in a contemporary realist setting, while Binks suggested that often genre fiction ‘does the heavy lifting’ in presenting boundary-pushing contemporary themes through a speculative or otherworldly lens.

There are always parallels and connections between real and fictional worlds, Scholte said. Her forthcoming novel, The Vanishing Deep, addresses environmental crises. Climate fiction, or cli-fi, is a growing genre especially in Australian literature, while books like Margaret Atwood’s The Handmaid’s Tale and The Testaments examine patriarchal control and abuse in an imagined regime. While some fantasy and sci-fi might offer escapism, many works resonate with real-world experiences.

Kenwood spoke of writing her novel around the time that Donald Trump was elected. ‘It’s a hard balance between escapism … teens are bombarded enough but they’re also leading the charge, so you want it to engage,’ she said.