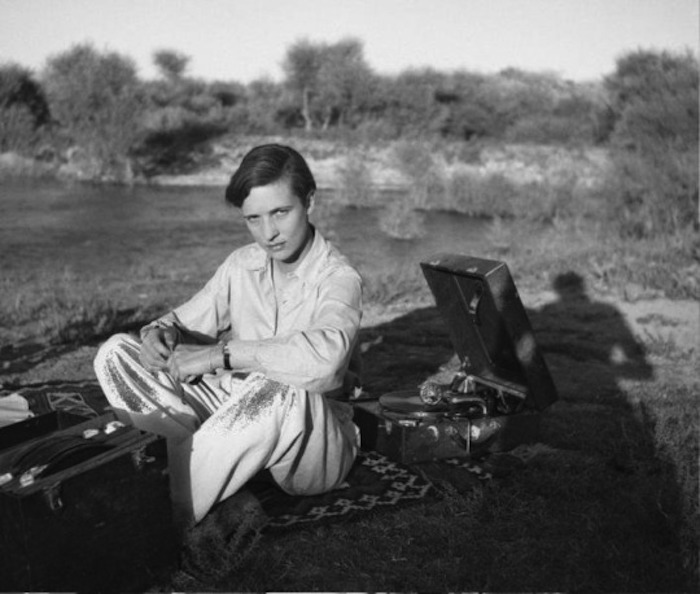

My fourth novel, A History of Dreams, tells the story of Margaret, Esther, Audrey and Phyl, four young women in pre-WW2 Adelaide who are learning to be witches. They have the power to change people’s behaviour by changing their dreams and are using this power to upend South Australia’s patriarchy. However, the rise of an authoritarian Australian government, allied with Nazi Germany, means they are suddenly facing a far bigger foe than the bosses, fathers and teachers of Adelaide.

A finished book feels as though it is the book it has always been. The Lion, The Witch and The Wardrobe was always about four children who find a new world in the back of a closet; Judy was always going to be killed by a falling tree branch in Seven Little Australians; The English Patient was always going to be about a man who loves a woman and leaves her in a cave in the desert. And A History of Dreams was always going to be about four young witches in Adelaide in 1937, trying to change the world with the power of dreams.

Except that it wasn’t.

How I wish we could see the drafts of all those other immutable books. Was there a version of Seven Little Australians where Judy loved boarding school and became a successful human rights lawyer, later mentoring Edith Campbell Berry on her arrival at the League of Nations? We will never know.

What I do know is that at one point during the five years it took me to write A History of Dreams – formerly known as The Semaphore Supper Club, The Dark Was Ours, In the Dreams Division, Whyalla, The Bystanders and The Bureau of Wellness – the lead character was called Nora and she was a 35-year-old woman working for a dream development start-up in Canberra in the 2050s and grappling with a shadowy government cabal executing people who refused to take wellness seriously.

For a while Nora changed form into Amelia, a typist working for the government and living in a women’s hostel in 1960s Canberra, where she stumbled across two wraithlike beings wired into a dream-generating machine in the basement of a nearby office building. Faint traces of Nora and Amelia can still be found in the published version, as Margaret infiltrates the Australian Government’s Dreams Division in the Bureau of Public Enlightenment, but these two women were otherwise briefly brought to life and then snuffed out altogether. Perhaps Hannah, the Buddhist, guppy-loving, peanut-allergic sister of Edmund, Susan, Lucy and Peter, suffered a similar fate as CS Lewis worked through the drafts of his Narnia tales.

Every novelist starts at a different spot. Some have a scene that grips them and won’t let them go. Others are desperate to tell the story of a particular character or recreate a compelling moment in history. For me, the start of a story is most often a troubling flaw in my own world.

In my novel A Wrong Turn at the Office of Unmade Lists, I wanted to know why we consider the things we imagine or remember less ‘real’ than the things we are currently living through. In Formaldehyde I wondered how much of our selves is intrinsic and how much is a factor of circumstances (I dramatically changed the ending of this novella four times before publication). In From the Wreck I was troubled by the damage that humans do to ourselves in failing to empathise with other species (the original version of this novel, about a shipwrecked man and his complicated relationship with a shape-shifting alien, did not include any aliens). And in what is now known as A History of Dreams, I was grappling with my own feelings of despair after ten years of working to raise awareness of climate change and ecocide – what do we do when our struggle is just but unwinnable?

Finding an answer for myself – or at least some small fraction of an answer – to that question is what drove the many versions of A History of Dreams. Nora’s world couldn’t help me – she was too brave and self-sufficient, too heroic, and the force she was fighting was too quirky. Amelia’s world wasn’t quite right either – it was too dystopian and crushing – and Amelia was too utterly powerless. Exploring the lives of Margaret, Esther, Phyl and Audrey (who used to be called Phoebe, but early readers complained about too many ‘P’ names) hit the sweet spot. I wanted a novel that didn’t end with a heroic but unrealistic victory. I wanted a novel that didn’t end with bitter and crushing defeat.

Neither of those choices seemed ethical or helpful for the reader who was themselves looking to find hope in dark times. The only world in which I could reach an ending that seemed right and true was one where stoic, rule-obsessed Margaret and fierce, eccentric Esther and tough, flirtatious Phyl and life-loving, revolutionary Audrey became friends and tried to figure out between themselves the best way to harness their differences, use their divergent strengths, deal with their icky feelings, take on a powerful but vulnerable authoritarian government and still have fun together. In Adelaide. In 1937.

It took two different settings, three different time periods, four revised endings and at least five abandoned major characters, but I got there in the end.

Jane Rawson’s A History of Dreams is out in April from Brio Books.