Does anyone draw anymore? I mean really draw as a central component to their art practice. I can just hear the squeals of uproar as dozens and dozens of contemporary artists yelling, “I do! I am a purist, that’s me.” Some may even burn their own wood to make charcoal. Super. The problem being that there are roughly 50,000 practising artists in Australia, and my good friend ChatGPT tells me that maybe as few as 1.5% draw exclusively. So, I ask again – who really draws these days?

This is not a value judgement. So, calm down. This is a cold, hard observation that, when considered, has ramifications. Sir Isaac Newton’s 17th century Third Art Law goes roughly like this: “For every art action, there is an equal and opposite reaction. Often, a very interesting one.”

Drawing has, since Homo sapiens scrawled on caves, been a significant form of expression. Possibly, in the mid-19th century – before the mass communication of print and image-making – drawing was a refined and informationally worthwhile skill for the middle classes and up. Indeed, in 2024 the biggest-selling artist in the Australian art market, Brett Whiteley, with $206 million-plus in sales, had a substantial drawing practice. His charcoal entitled Portrait of Wendy achieved $273,000 in 2002. Whiteley died 33 years ago.

Could it be that drawing, like the work of Brett Whiteley, is without doubt important; however, it is today largely a practice of an earlier generation? I bring this possible reality to the boil, as drawing is, in terms of declining numbers, obviously on the wane – possibly not in its centrality to the actual building blocks or making of art (but, yes, maybe), but most definitely in the Australian art market’s acceptance of this practice as contemporary mainstream and stand-alone.

Talk to any third-year Bachelor of Fine Art student and you’ll likely find far more digital tablets than sketchbooks. Life drawing classes, once the backbone of artistic training, now seem like electives – if they exist at all.

Curators still write essays on the intimacy of line and the honesty of drawing. But curators aren’t often the ones reaching for their wallets, while AI-generated images and 3D rendering software have democratised the skill levels needed in technical image-making.

Important though it is, drawing is down on the mat, and the count is at eight seconds.

Applying our Newtonian Art Law of action and reaction, there are a number of established drawing-exclusive prizes in Australia. The pick of the bunch being the Dobell Drawing Prize, Kedumba Drawing Award, Paul Guest Prize, Adelaide Perry Prize for Drawing, Jacaranda Acquisitive Drawing Award (JADA), Lyn McCrea Memorial Drawing Prize and so on. There is a lot of art prize space given over to what increasingly looks like a decline in an art practice, public interest and the market. On the face of it, should these prizes double down on supporting a niche practice, or should they, at least at their governance level, have the uncomfortable but necessary, ‘we need to talk about Kevin’ moment?

Moving forward, I think drawing prizes should be on the ‘watch and listen’ stance.

In a Newtonian art world, as our collective interest in drawing decreases, maybe our interest in photography is, in response, accelerating? Maybe it is not drawing, but photography that is today’s building block for image-making – whatever the art practice. We are, after all, photographers one and all. Every smartphone has a camera.

As of 2024, there are approximately 4.88 billion smartphone users worldwide, representing about 60.42% of the global population. However, due to individuals owning multiple devices, the total number of smartphones in use globally is around 7.21 billion. Again, I do not see too many people carrying sketchbooks.

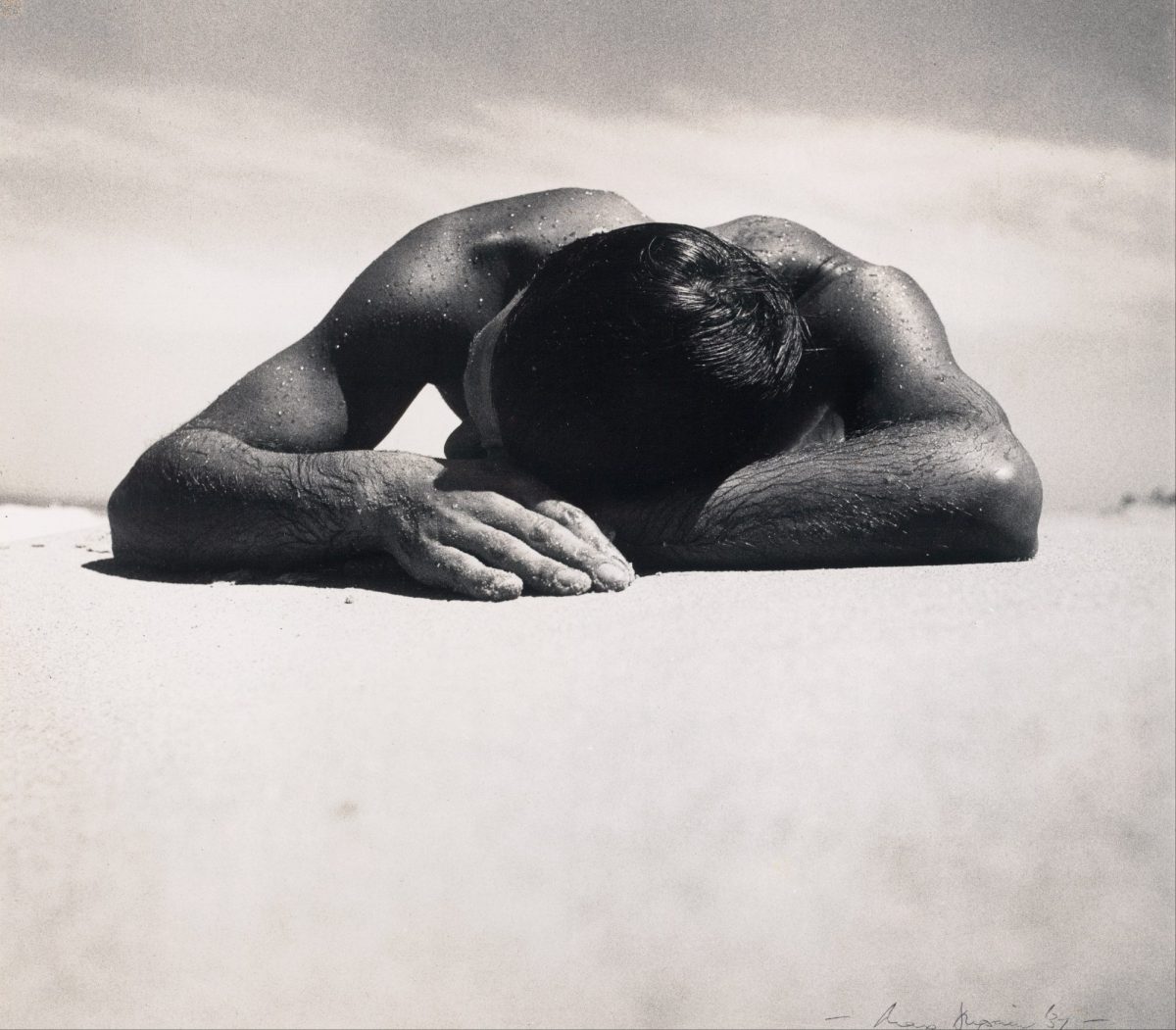

The Australian art market established a new benchmark for photography in April, with the auction house Smith & Singer achieving $270,000 for Carol Jerrems’ Vale Street, 1975. The previous record price for the artist and image was $171,818 in November 2023 with Deutscher and Hackett. Petrina Hicks, by far the more consistent contemporary artist in this field at auction, has obtained regular strong results—$67,500 for Shenae and Jade, 2005 in May 2025; $47,636 in July 2021 for the same image; and $49,091 for Venus, 2013 in July 2024. And mid-century stalwart Max Dupain’s Sunbaker, 1937 also saw strong recent results at auction, achieving $44,182 in August 2024, $76,705 in November 2024, and $39,273 later that same month with Deutscher and Hackett. These prices are becoming secondary art market consistent and are recent and/or generationally relevant.

As photography is now almost monthly creating new sales benchmarks in the art market, we will see photography prizes on a clear growth trajectory. Notable photography prizes in Australia include the Australian Photographic Prize, Australian Photography Awards, Mono Awards, Bowness Photography Prize, Galah Regional Photography Prize, Head On Photo Awards, Moran Contemporary Photographic Prize, National Photographic Portrait Prize, National Emerging Art Prize and Nikon-Walkley Press Photography Awards. As the art world falls and rises, it is these prizes that will have a naturally expanding audience and relevance to collectors and our art market.

Photography speaks volumes to contemporary life: surveillance, identity, speed and ease of use, universality and the perennial truth versus fabrication Trumpesqian debate. These are key concerns of the 21st century condition – and contemporary art practice.

Read: The latest photography news at a glance

While finally and quite powerfully, photography is native to the platforms that now define international cultural capital – Instagram, TikTok, Printerest, Flickr, Tumblr and digital portfolios. After all, my gentle reader, sketches don’t go viral; photographs do.