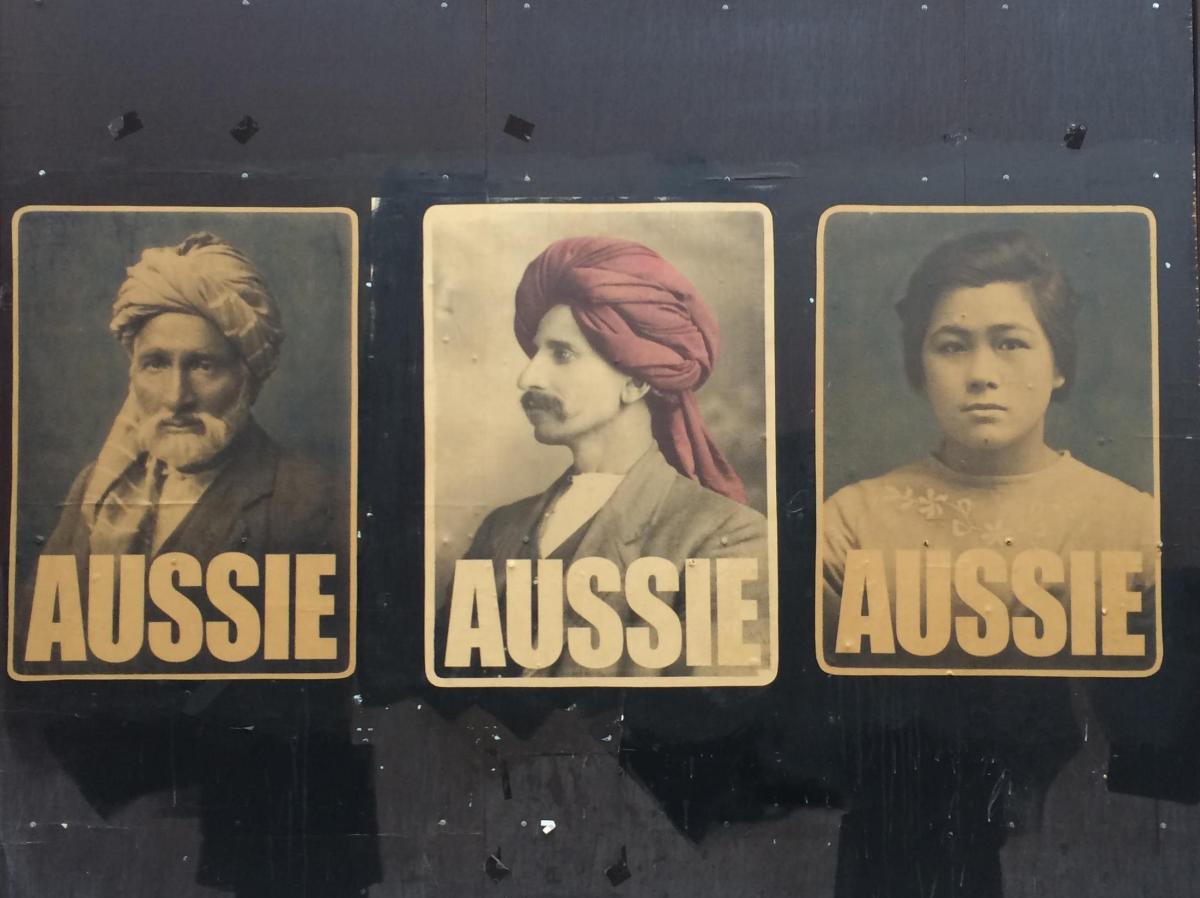

Three posters from the Aussie series. Image supplied.

So what is great propaganda? How about something like, Fuck off, we’re full! They’re fun words to fart out of your face because of the Fs. Give it a try.

It’s fun to pretend, to imagine what it’s like to hold the exact opposite of your convictions. It’s fun to get as close as you can, to really feel what they feel. You owe it to them, because that’s what you’re asking them to do for you. That’s how I came up with this:

The poster that started the campaign. Image supplied.

For anyone unfamiliar with the often forgotten second verse of the Australian national anthem, it goes like this:

For those who’ve come across the seas

We’ve boundless plains to share;

With courage let us all combine

To Advance Australia Fair.

Pretty solid stuff, right? My favourite part is the suggestion of courage. Because why courage? Why not kindness or caring? The suggestion of courage simultaneously admits that fear is inevitable while also providing a solution to fear. You can’t cure fear with kindness.

But courage, on the other hand, flatters the conservative mind. It’s quite different to an appeal to empathy, which can leave the viewer feeling vulnerable and actually more susceptible to fear. Obviously the bit about having ‘boundless plains to share’ is a bit problematic, but we’ll get to that.

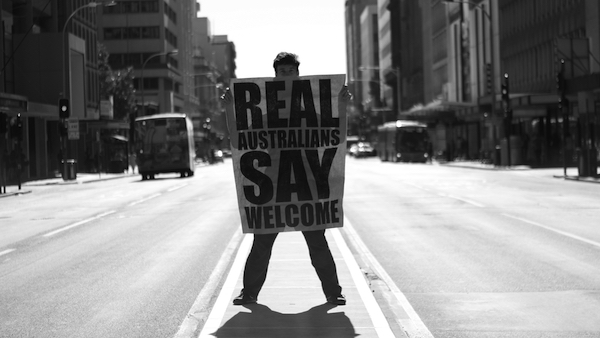

I invoked the anthem in my launch video for the ‘Real Australians Say Welcome’ campaign because I think one of art’s jobs is to reach back into our history and interrogate the values we claim to protect. I wanted to use the anthem to show that sentiments like ‘Fuck off, we’re full!’ and ‘Stop the boats’ are actually debasements of Australian values. Removing the burden of empathy and appealing to the very same patriotism that conservatives want to protect, I thought to myself, could be a novel strategy.

At the end of 2014, anyone whose senses were working correctly could detect the storm that was brewing on the Australian political landscape. ISIS beheading videos began appearing in August, and December brought the 16-hour Lindt Café siege in Sydney, which shook loose an avalanche of fear. Before we had time to comprehend that the gunman was mentally ill and had no real connection to ISIS, seemingly every Australian had considered the possibility that this was the new normal, that we’d all need to get used to terrorism on Australian soil. Then, on 7 January 2015, the Charlie Hebdo shooting erupted in Paris. That sort of fear doesn’t just evaporate overnight. It hangs around and searches for answers.

Some people found the answer they needed in the fact that the Lindt Café gunman was Muslim and a refugee. Some of those people joined groups like Reclaim Australia and the United Patriots Front, which quickly attracted media attention despite their meagre membership. Into the limelight leapt Pauline Hanson 2.0. Gone was her anti-Asian rhetoric of the 1990s. The new Pauline was a near carbon copy of her former self, only now she feared ‘Islamic terrorism’. Further up the food chain of political influence the rhetoric was less blustery. Those with real power could exploit the growing anti-Islamic sentiment by gradually increasing restrictions against asylum seekers, thereby winning votes.

The feeling was reminiscent of the Cronulla riots10 years earlier, but this time was different. This time all Australians were feeling the fear. Everyone was afraid, but the majority of Australians were able to control their fear and, as a result, resented all the more those who surrendered to their xenophobic impulses.

I don’t hate bigots, I hate the bigot in me.

The above phrase popped into my head just now as I am writing this. I think it captures the feeling I’ve had for a very long time. I know it’s not the most popular sentiment, but I really believe that it’s the most powerful way to confront bigotry. ‘Real Australians Say Welcome’ is a way of expressing that idea.

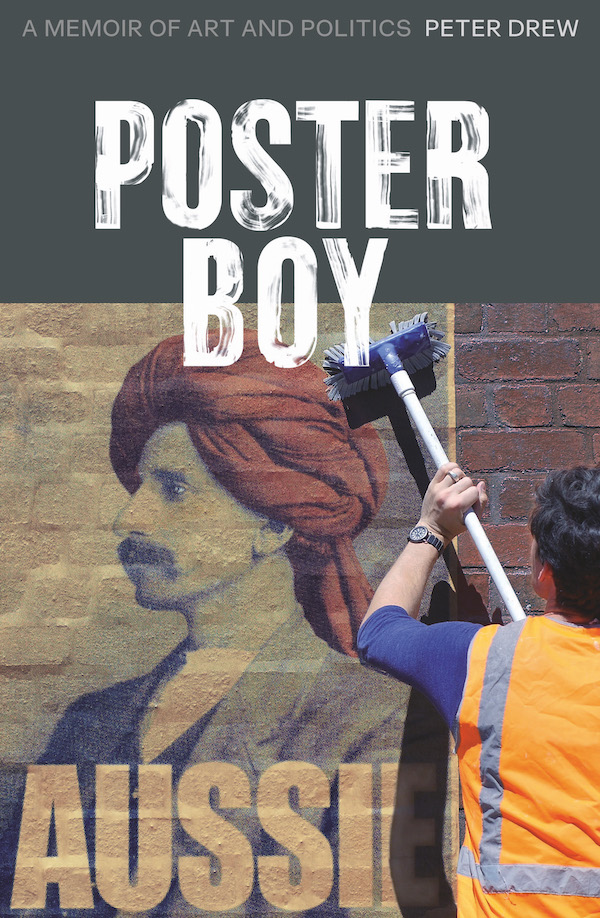

Cover of Peter Drew’s memoir Poster Boy. Image supplied.

At this point I need to be careful, because it’s very easy to bestow upon oneself a sense of retrospective self-awareness that exceeds the reality of the moment. In early 2015 I simply had a gut feeling that my poster could capture the mixture of frustration and dismay many Australians were experiencing. Part of me wanted my art to effect ‘positive change’ on the Australian political landscape, but another part of me wanted something personal. I want to be honest about that part of myself because I think it’s something I have in common with many of the people whose views I oppose.

Beneath my carefully crafted image of noble political intentions, I was also hiding a personal desire for self-transformation. At the time I didn’t think it had anything to do with my family. It was just a feeling. I wanted to leave my old self behind and this poster seemed like the perfect way to do it.

All I needed to do was paddle it out far enough to catch a big wave in the approaching storm. I wanted to play in that storm. I wanted to meet some monsters and do battle. I wanted to see what I was capable of. Above all, I wanted the experience to change me into someone new. Until now my work had attracted the modest attention you might expect for an Adelaide-based street artist. I was a nobody. But I did know a few things about art, especially the power of the spectacle.

Street art is a bit like real estate: it’s all about location. If I’d simply hung my poster in my local gallery, it would have been ignored.

Street art is a bit like real estate: it’s all about location. If I’d simply hung my poster in my local gallery, it would have been ignored. If I’d stuck up my posters without announcing my intentions, the response might have been similar. Instead I packaged the whole project into a story, which I could feed to media outlets. I created a spectacle of one artist on a righteous crusade to hold Australia accountable to its own national anthem. In this sense, the artwork is not just the poster design, it’s also the journey the audience is invited to follow. By creating a spectacle, my posters could be seen on the street, online and in the news. Multiple locations, multiple exposures, until the person on the street is forced to turn to their friend and ask, annoyed, ‘What’s with that poster I see everywhere?’ And with that, you’ve got them, whether they like it or not.

In March 2015 I launched an online crowdfunding campaign promising to stick up one thousand ‘Real Australians Say Welcome’ posters across the country. The campaign made no mention of asylum seekers. I used footage of the Sydney 2000 Olympic Games in which Julie Anthony sang the anthem. The tone was warm, inviting and playful. The strategy worked. I raised $8384, more than I needed. It was time to hit the bricks.

This is an extract from Peter Drew’s Poster Boy.