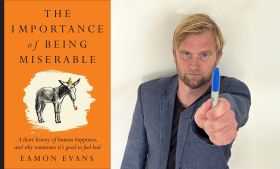

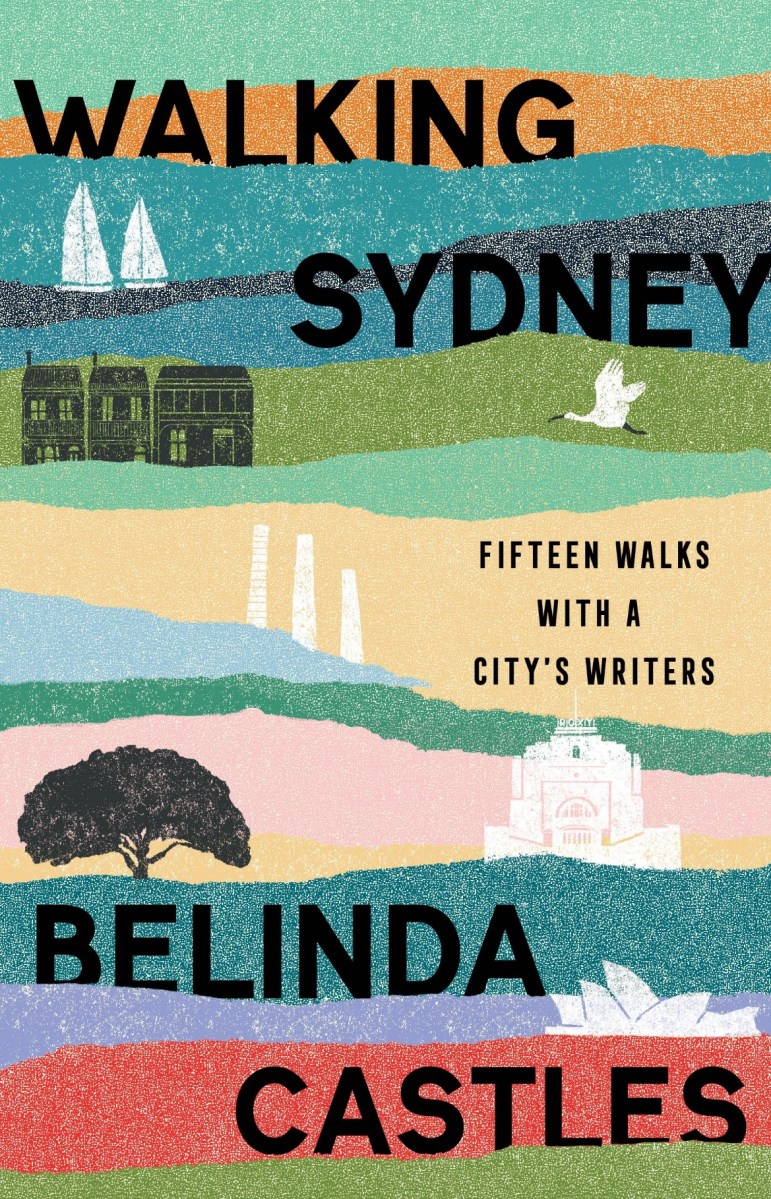

In this edited extract from Walking Sydney: Fifteen walks with a city’s writers, author Belinda Castles explains why her love of Sydney only grown the more she has walked in it.

Walking Sydney: quick links

There is a rust-coloured beach in northern Sydney where I have long walked in the evenings. Ferns and scrub and a little waterfall spill down the sandstone headland. Houses teeter on the cliff. In the last soft light, I wander along the cool sand, and the mysteries of houses and other people beckon as the shapes of the world become indistinct.

From my early days in Sydney, my walks have carried the strangeness of encounter; I travel ever further into the labyrinth to see what I will find.

Heading out from my first Sydney home, a condemned studio in Elizabeth Bay, I walked steep staircases and hills, passing continually from shadow into the dazzle of light on water. In Chippendale and Newtown I breathed petrol fumes and jasmine among terraces and curious old factories, peering down alleys, following my feet.

The long beach at Dee Why drew me down to stroll the tideline, lost in time as I traced the land’s edge. From my home now on a bushy ridge I plunge into the evening racket of frogs and kookaburras, my mind both here in the vivid dusk and somewhere else entirely.

In my wanderings I have walked stories into being. Down at the beach, I am in a real place of Norfolk Island pines and spiral shark eggs and footprints filled by the tide, but also a place of memory and invention. My kids still traipse across the hot sand with boogie boards. A character is stopped in her tracks by a glimpse of dangerous blue tentacle.

Walking Sydney: many stories

We move among many stories in Sydney. Writers inscribe the world with the traces of their thoughts, leaving bright trails behind them. Walking out of my own neighbourhood and across the city, I discover the threads laid out across the streets.

At the southern pylon of the Harbour Bridge, I imagine encounters between Patyegarang, a local girl, and William Dawes, a First Fleet officer, as they teach each other language. In offering words for things, actions and sensations, they are sharing knowledge about the lives of their people.

Kate Grenville’s novel The Lieutenant and Ross Gibson’s speculative history 26 Views of the Starburst World placed these images and ideas in my mind. They flicker as I walk the harbour path under the thundering bridge, deepening my sense of what this place holds, its lives and possibilities.

In Surry Hills the cottages, terraces and factories call up the world of Ruth Park’s The Harp in the South and Poor Man’s Orange, of families and lodgers packed into poor housing, of the many factories drumming, of the men staggering into the lanes from the pubs at six. As my train pulls into Central, I look up into the steep streets and see an old warehouse, and that world shimmers behind this one.

Walking Sydney: understanding place

How can this city be understood? This brand-new city, through which the whole world flows, on the edge of an ancient continent. First Nations writers offer a sense of time so deep and present that the city can seem like a thin crust on the living land. The children of diasporas write stories in which the old country and the new, all the generations, breathe in the same bodies.

Those once kept to the shadows hoist their stories up in bright flags. Dreamers wander every suburb, finding ways to put their world into words. Imagine a map of these dreams, made like all maps to be read by mind and body.

Walking Sydney: psychogeography

Readers of the city carry such maps with them. Walking is a means of looking and listening that can be done quietly and at a pace that aids perception, slowly enough to absorb textures and atmospheres, quickly enough to keep the mind alive and the terrain gently shifting.

Rebecca Solnit tells us in Wanderlust: A History of Walking that the great urban thinker and walker Walter Benjamin was fascinated by cities ‘as a kind of organisation that could only be perceived by wandering or browsing’. Benjamin was a psychogeographer before the term existed, one interested in the effect of cities on people and in what they make of this influence, culturally and politically.

Psychogeography holds walking as its central method of perception: a form of reading – ‘browsing’ – open to serendipity, to responding to the flows of the city but interested always in going against the grain.

The term ‘psychogeography’ was coined by Guy Debord of the Situationists, who theorised walking – or the ‘dérive’ or ‘drift’ – as a form of resistance to the consumerist organisation of cities. In ‘Theory of the Dérive and Definitions’ (1958), he wrote:

In a dérive one or more persons during a certain period drop their relations, their work and leisure activities, and all their other usual motives for movement and action, and let themselves be drawn by the attractions of the terrain and the encounters they find there … from a dérive point of view, cities have psychogeographical contours, with constant currents, fixed points and vortexes that strongly discourage entry into or exit from certain zones.

Walker-writers have sought to navigate and resist the imperatives and flows of the city, to unearth its real stories by moving through it on foot, in often subversive ways. Merlin Coverley, in Psychogeography, discusses those writers of London and Paris who see ‘the city as a site of mystery and seek to reveal the true nature that lies beneath the flux of the everyday’.

These writers have seen in their wanderings a means to counteract the numbing effects of economic forces, conceiving of urban encounters that drift off prescribed paths. The slowness of walking, necessary for noticing and consideration, is a way to set oneself against the urgings of this frenetic world, in which every moment of our time might be consumed by speed and noise.

Walking Sydney: reading the city

In making Walking Sydney, I wanted to enlist the key elements of these practices – slow browsing, unearthing, drifting off prescribed paths – to travel more deeply into the life of the city than I had before in my reading and solitary walking. I invited fifteen writers whose work engages with many very different locations in Sydney to walk with me, to talk about particular places and how they know them through their writing and lives.

Psychogeography has been beholden to the romantic strolling figure of the ‘flâneur’: solitary, male, aloof. These walkers are friendlier, more engaging companions, willing to share their knowledge and memories, their sense of community, often with urgent purpose. In walking us through their worlds, they make openings in the fabric of the contemporary city through which we might glimpse the experiences, histories and visions that make the dreamlife – the real life – of this city.

The walks were true drifts, a few hours’ absconding from busy workaday time into the city’s full, multidimensional time, each moment of the present imbued with those that led to it and those that might yet come.

All cities change, all the time, but there is an urgency to our reading of the city and its meanings amid the profound pressures of a changing climate and the flux of development that transforms Sydney’s familiar shapes overnight. Beaches shrink to rocks in great storms. New towers rise between one visit to the city and the next.

As you travel through the city on bridges and freeways, the city reconfigures in fast motion around you. There was a sci-fi film shot in Sydney in the 1990s: Dark City. A man in a perpetual night-time city retains no memory of his life from one day to the next. He encounters a group called the Strangers who rearrange the city while the inhabitants are sleeping and re-form their memories and identities.

You see glimpses of Sydney sandstone and streetscape as the city morphs but it happens too fast for you to orient yourself.

How to capture memory and meaning before it is severed further from its material foundations? Not in the spirit of preserving a city of the past, but to record what this place has meant and means now, in order to consider, perhaps, what it might yet be.

We all make this city every day – with our lives in it, with the movement of our bodies through its streets and parks and shorelines, and with our thinking, dreaming selves.