Whether the book is better than the film version is a perennial discussion point when it comes to adaptations of novels … but leaving that aside for a minute, here are some recent, not-so-recent and soon-to-be here film adaptations of Australian novels worth looking out for. Are there others you’d like to see here? Let us know and we’ll add them to the list.

See also: Australian books adapted into TV shows: ones to watch

The Dry (2021)

This box office hit thriller starring Eric Bana is based on the bestselling 2016 debut novel of the same name by Australian author Jane Harper. To date, more than one million copies of the book have been sold worldwide, and the follow-up to The Dry is set to hit cinemas soon, based on Harper’s 2017 novel, Force of Nature.

As Mel Campbell wrote for ScreenHub in her review of The Dry in 2020: ‘The film’s strength is the way it overlaps Aaron’s flackback sequences with his present day pilgrimages to the now-desiccated sacred sites of his youth. Here, as Aaron remembers the milky-brown river water and gentle grey-green foliage, Ellie’s river-damp skin and her campfire-lit face, the drought finally feels like a genuine metaphor for his loss as he walks through those same trees, now dead and colourless, and along the canyon the river has become.’

Image: Pan Macmillan Australia.

The Book Thief (2013)

When a book comes with ‘over eight million copies sold’ on the cover, it’s safe to assume it’s found an audience.

Set in Nazi Germany during World War II, Markus Zuzak’s 2006 novel – narrated by Death no less – follows the adventures of young Liesel Meminger and presents viewpoints from many of the war’s victims.

The 2013 film of the same name was co-written by Zuzak and Michael Petroni, and stars Sophie Nélisse, Geoffrey Rush and Emily Watson.

The film has a 49% critics rating on Rotten Tomatoes, with Charlotte O’Sullivan writing in the London Evening Standard: ‘It’s certainly pretty to look at, reminiscent of those Disneyland parades where horses are much in evidence, but their excrement (thanks to neat little sacks attached to the creatures’ nether regions) never soils the ground.’

Image: Pan Macmillan Australia.

He Died With A Felafel in His Hand (2001)

John Birmingham’s 1994 memoir takes a grimly funny look at his many experiences in share houses in Brisbane and elsewhere in the 1980s and early 90s – including finding a dead heroin addict in one house, as referenced in the title.

It was adapted into a successful stage play and then, in 2001, a Richard Lowenstein film starring Noah Taylor, Emily Hamilton and Romane Bohringer.

It has a 79% audience rating on Rotten Tomatoes, with David Rooney writing in Variety in 2001 that it: ‘depicts a generation approaching 30 and struggling to make its mark on the world with little sense of commitment or focus. Piloted by a likeably deadpan turn from ever-reliable Noah Taylor, this carousel ride of bizarre characters and out-of-control situations rarely remains stationary long enough to allow its themes to gel fully, but gradually coalesces into a reasonably satisfying whole.’

Image: HarperCollins Australia.

True History of the Kelly Gang (2020)

Published in 2000, Peter Carey’s True History of the Kelly Gang won the Booker Prize and the Commonwealth Writers Prize the following year.

Though fictionalised, the text (in its prose style and certain details) takes inspiration from Ned Kelly’s The Jerilderie Letter – a would-be manifesto by the infamous bushranger written in 1879.

The 2020 film by Justin Kurzel, starring George MacKay, Essie Davis, Russell Crowe and Nicholas Hoult, follows this fictional version of Kelly’s life, from his childhood in the 1860s to his notorious life of crime and eventual capture.

As Cary Darling wrote in the San Francisco Chronicle: ‘True History of the Kelly Gang may not be history as recorded by historians, but it’s history as recorded by a director with verve and vision. In this case, that’s enough.’

Image: Penguin Books Australia.

The Light Between Oceans (2016)

M L Stedman’s debut historical fiction novel tells the story of Tom, who returns traumatised to Australia following service in the World War I trenches to become a lighthouse keeper on the isolated (and fictional) Janus Rock off the southern coast of Western Australia, and his unexpected romance with a correspondent called Isabel.

The couple marry and, unable to have children, informally adopt an infant girl who washes up on shore in a dinghy with her dead father.

The 2016 film adaptation by Derek Cianfrance stars Michael Fassbender, Alicia Vikander and Rachel Weisz, was praised widely for its acting and cinematography, but divided audiences and reviewers overall.

It has a 62% critics rating on Rotten Tomatoes, with Kevin Maher of The Times (UK) describing it as a ‘grimly saccharine and interminably trite sea-sodden weepie’.

Image: Penguin Books Australia.

Schindler’s List (1993)

Steven Spielberg’s epic, seven-Oscar-winning 1993 film about the World War II industrialist Oskar Schindler, who becomes increasingly concerned for the welfare of his Jewish workforce in Nazi Germany, is based on the 1982 novel Schindler’s Ark (renamed Schindler’s List in the US edition) by the Australian novelist Thomas Kenneally.

It won the Booker Prize in 1982 and the Los Angeles Times Book Prize for fiction the following year. In a career spanning 60-plus years, and still going strong, the novel – thanks to the film adaptation – is Kenneally’s most famous work to date.

Responding to praise of its ‘formal brilliance’ with The Booker Prize‘s website in 2021, Kenneally wrote:

‘No, it’s nothing. You have to read my latest [The Dickens Boy]. I like to think it’s not bad for an old fart like me. It shows I’ve still got good work left in me.’

Image: Simon & Schuster Australia.

Picnic at Hanging Rock (1975)

Joan Lindsay’s 1967 novel was apparently written over the course of just four weeks at her home on the Morning Peninsula. It tells the story of a group of girls from an Australian boarding school who go missing during an expedition to Hanging Rock on Valentine’s Day, 1900.

It’s fictional but is framed as a true story, with readers invited to ‘decide for themselves’ whether it is, in fact, true. Its unresolved conclusion only adds to the feeling that maybe, just maybe … were those missing girls real people?

Peter Weir’s 1975 film version stars Rachel Roberts, Helen Morse and Jacki Weaver and is described on Rotten Tomatoes as: ‘moody, unsettling, and enigmatic – a masterpiece of Australian cinema and a major early triumph for director Peter Weir’.

Fremantle also produced a TV series of the same name in 2018 starring Natalie Dormer and Lily Sullivan.

Image: Text Publishing.

Dirt Music (2019)

Tim Winton’s novels are no strangers to adaptation, with films such as Breath (2017), Blueback (2022), In the Winter Dark (1988), That Eye, the Sky (1994), and the 2011 TV miniseries of his 1991 novel Cloudstreet.

His 2001 Miles Franklin Award-winning novel about an illegal fisherman in WA who comes to see life as a ‘project of forgetting’ was given the film treatment in 2019 by the director Gregor Jordan, and stars Kelly Macdonald, Garrett Hedlund and David Wenham.

It currently has a 27% critics rating on Rotten Tomatoes, with Stephen Romei writing in The Australian that: [Winton’s] not an impossible author to film, but a challenging one to translate from page to screen. Chris Kennedy in The Canberra Times gave praise to its star, stating that: ‘Garrett Hedlund looks like a fourth Hemsworth, sun-bleached hair and dreamy eyes.’

Image: Penguin Books Australia.

Monkey Grip (1982)

Critics were divided in their appraisals of Helen Garner’s 1977 debut novel at the time of publication (largely for its subject matter), but that didn’t stop it selling well, and it’s now regarded as a modern Australian classic. The tale of Nora, raising her daughter in a series of share houses in Carlton, Melbourne, and her relationship with Javo, a heroin addict, also ushered in a new wave of grittier Australian novels.

Ken Cameron’s 1982 film, starring Noni Hazlehurst, Colin Friels and Alice Garner, leans into the story.

Bernard Hemingway, on Cinephilia, described the film as ‘well watchable’ adding that: Noni Hazlehurst, who won an AFI Best Actress award for her performance and has since gone on to a varied film and television career, is captivating as Nor’, whilst Colin Friels, although not particularly believable as a junkie, is highly serviceable as her dramatic foil.’

Image: Text Publishing.

Mary Poppins (1964)

It’s hard to think of Mary Poppins without immediately seeing Julie Andrews and Dick Van Dyke in the blockbuster 1964 film (and probably, to a lesser degree Emily Blunt – and, again, Dick Van Dyke) in the 2018 sequel, Mary Poppins Returns).

But fewer of us might reflect on the fact the eight-part children’s series of books was written by the Australian-British author P L Travers.

Born Helen Lyndon Goff in Queensland, Travers attended boarding school in Sydney and worked as an actress before emigrating to England at 25.

Saving Mr Banks, a film based on Walt Disney’s long-standing efforts to buy the Mary Poppins film rights from Travers, starring Emma Thompson and Tom Hanks, was released in 2013.

Image: HarperCollins Australia.

Storm Boy (2019)

As per IMDb: ‘When Michael Kingley, a successful retired businessman starts to see images from his past that he can’t explain, he’s forced to remember his childhood and how, as a boy, he rescued and raised an extraordinary orphaned pelican, Mr Percival.’

Directed by Shawn Seet and starring Finn Little as Storm Boy, the 2019 adaptation is based on the popular 1964 Australian illustrated children’s novel by Colin Thiele, set in the Coorong region of South Australia.

Peter Rainer, in FilmWeek, wrote: ‘It’s sort of disposable, but kind of sweet.’

Image: New Holland Publishers.

Tomorrow When the War Began (2010)

Stuart Beattie’s 2010 film is an adaptation of John Marsden’s internationally bestselling novel of the same name, the first in a seven-book series of “invasion novels” for young adults published between 1993 and 1999.

It follows a small band of teenagers who form a resistance to an unspecified foreign power wreaking havoc across Australia.

In a 2018 interview with the ABC, Marsden said he would not have written the book now, given Australia’s current treatment of refugees: ‘When I see people who arrive here legitimately seeking refuge and shelter, and they are treated as the scum of the Earth and they are sentenced to awful detention and sometimes death by both major political parties without any apparent scruples or conscience exhibited by those parties, then that would put me in a very different position when it came to writing a book about threats to Australia, because demonising people like that is unforgiveable and it’s disgusting and it’s an ongoing obscenity in our lives.’

Image: Pan Macmillan Australia.

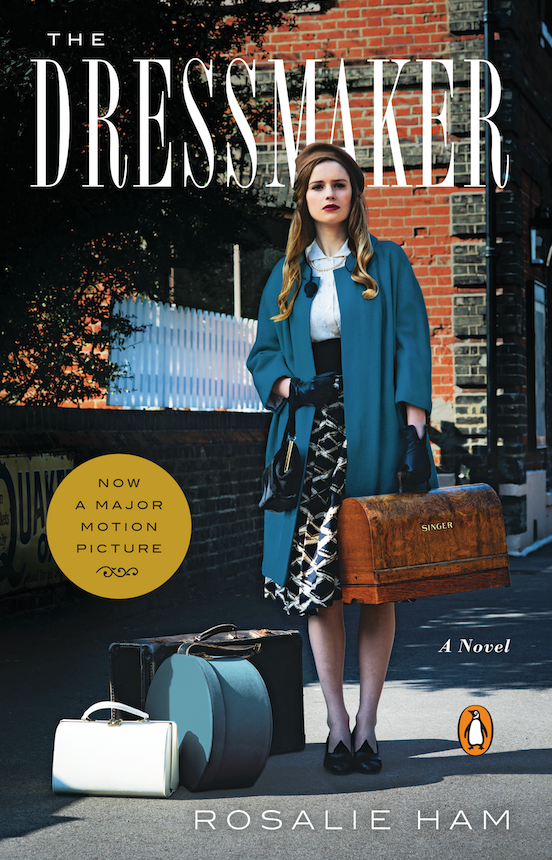

The Dressmaker (2015)

Jocelyn Moorhouse’s 2015 film starring Kate Winslet, Judy Davis and Liam Hensworth was adapted from the 2000 satirical novel by Australian writer Rosalie Ham.

It follows Tilly Dunnage, who returns to the small Australian town she was ostracised from as a child, now as a dressmaker of great repute whose creations are irresistible to the local women, despite her family still being despised. Does Tilly have a darker agenda than acceptance from her one-time tormentors? She certainly does.

The film received mixed reviews, with fans including Sara Michelle Fetters, who wrote on MovieFreak that: ‘Moorhouse’s willingness to push the envelope and dive into the darkest aspects of the tale with such macabre relish allows the emotions swirling within this maelstrom to resonate all the deeper.’

Image: Penguin Random House.