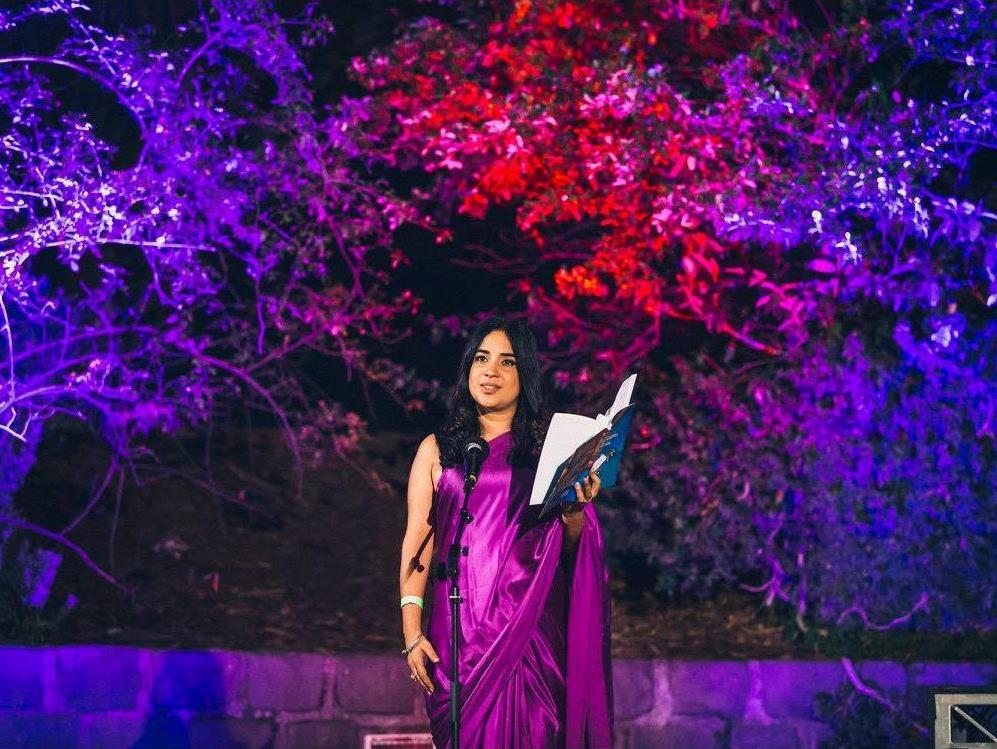

Poet and activist Sadaf Saaz at One Night Stanza, Women of the World Festival Melbourne. Photo: Rachel Main.

The night before poet and activist Sadaf Saaz was due to read at the Women of the World festival, she had planned to memorise her work. Instead she found herself grappling with news of a suicide attack in her Bangladesh home town.

‘I had to give myself permission that it was okay to not read from my book by heart because I just had so many things. I’ve come here but I’m also running my business, getting an article in, I’m confirming invites for the next Dhaka Lit Fest…there’s just been another suicide attack in Dhaka as well, so I’m connecting with people. I just had to give myself permission to read the poem out.’

In a culture where our understanding of self-care often amounts to time to get a manicure or indulgence in retail therapy, Saaz’s story shared at a panel on self-care was as a timely reminder that real self-care is not about pampering ourselves. Rather it requires understanding where we fit in today’s social and political context, and the threats that can create to our bodies – recognising some bodies are more vulnerable than others.

For women living with violence, women of colour and other marginalised groups, self-care is necessary and hard-won behaviour. As Audre Lord said, ‘Caring for myself is not self-indulgence, it is self-preservation, and that is an act of political warfare.’

Radical self-care is a long way from the discourse occupied by advertising models simpering ‘because you’re worth it’ in an effort to sell hair dye. Jessa Crispin, author of Why I am not a feminist: A feminist manifesto, is scathing of the consumer habits developed in the name of looking after ourselves.

‘The idea of self-care was about taking care of yourself and make sure that you’re healthy because the system is so fundamentally working against you… somehow we’ve interpreted this as, “Oh yeah, you should go get your nails done, that’s so important”. Look, it’s not self care if someone else is doing your nails. That’s exploiting immigrant labour,’ writes Crispin.

From politics to pampering and back

The self-care movement began by encouraging patients to take responsibility for their own health by adopting healthier habits but it built momentum in the 1960s and 1970s through progressive politics.

Self-care, in the context of civil rights and women’s liberation was a political act – and an important one. ‘Women and people of colour viewed controlling their health as a corrective to the failures of a white, patriarchal medical system to properly tend to their needs,’ wrote Aisha Harris for Slate. It was part of a push to redefine health care and to centralise a conversation about the intersection of race, gender and class, and how these social factors impact health and wellbeing.

But neoliberalism and capitalist enterprise co-opted the terminology and it has become the stock-in-trade of a new industry in personal trainers, beauty spas and wellness practitioners.

‘The advertising industry has nudged self-care away from introspection and towards reflexive consumerism,’ wrote Ester Bloom. This is an individualist turn inwards, combed through with a “treat yourself” commercialised mentality, one that typically targets women.

But many feminists reclaim the terminology, emphasising that it is about kindness to oneself and awareness of one’s value not commodification.

That need is greatest for women who are most marginalised, said writer and activist Mahogany L. Browne. ‘I’ve learned that a lot of women, and a lot of women of colour, we take to task being everything for everyone. I think women do it [more often], like, mothers are the backbone. I’ve learnt to tap out and that does not make we weak, that does not make me a bum, it does not make me unworthy of love and celebration, it just means that if I don’t preserve myself and my sanity and my emotional stability, I won’t be any good to anybody.’

As co-founder and co-director of Dhaka Literary Festival, Saaz understands the threatening context of her work demands self-care as a form of self-preservation.

‘Last year going ahead with the festival was very risky. We had threats on the festival; I felt a huge sense of responsibility for everyone else, including my family,’ she said.

‘It’s not that you need to remove yourself from your current life, but just that you need to be sensible. Let’s say switching off for half an hour. Or if you have little kids, switching off for 15 minutes and meditate. Give yourself permission.’