This week, the NSW government arts agency Create NSW announced it would ‘redistribute’ Regional Arts NSW’s annual grant of $455,000, despite NSW arts investment being amongst the lowest per capita in Australia.

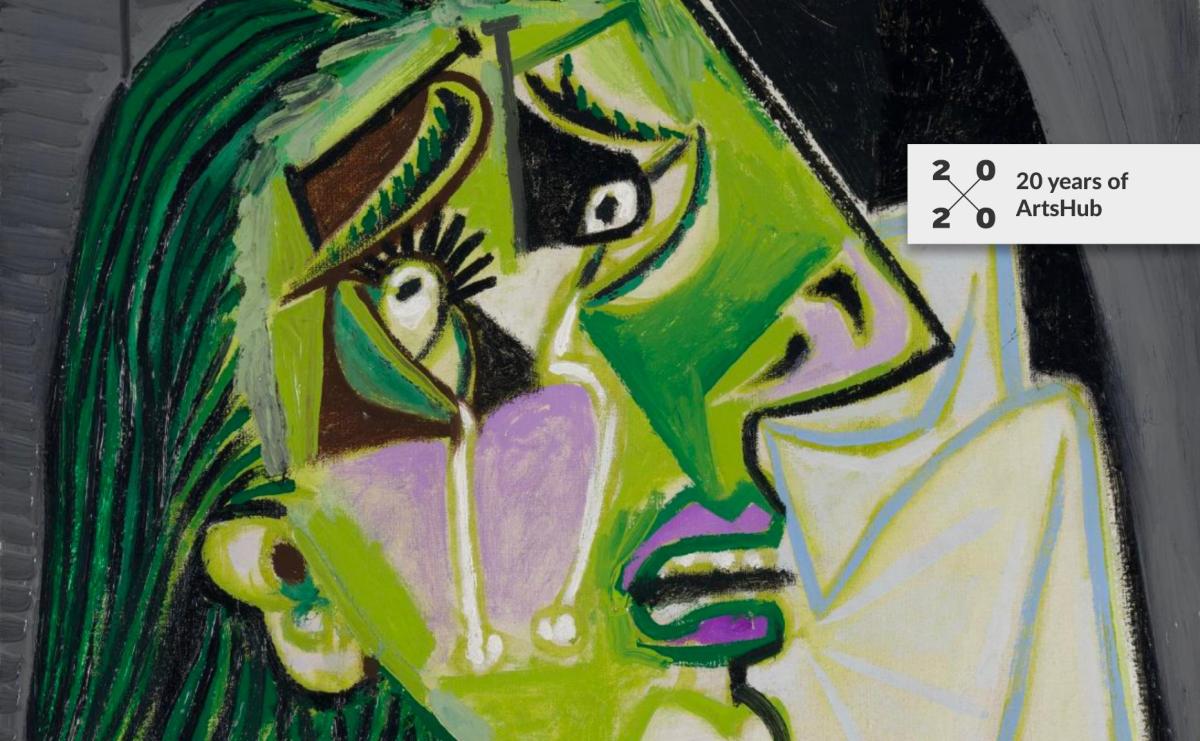

Sadly, defunding is not a new problem: in recent years we’ve witnessed the Brandis raid, Abbott-era cuts and more recently, the Morrison Government’s dismantling of the Federal Department for the Arts. As part of our 20×20 series celebrating 20 years of ArtsHub, we revisit Richard Watts’ story from 2013, demonstrating just how long the sector has been shouldering this burden of shrinking funds.

* * *

For any professional artist or arts organisation, failure to secure the level of project funding expected – or in a worst-case scenario, the total axing of previously recurrent funding – can feel like a crippling blow.

When several key organisations failed to receive funding (November 2013), as well as causing shock, insult, loss of confidence and consternation, such a scenario can have significant long-term ramifications, curtailing projects and even forcing organisations to close.

But a failure to secure funding, whether all or some, is not the end of the world. There are other funding bodies out there, and other means by which projects and productions can go ahead, as experienced arts professionals know – and thankfully, are only too willing to share.

Don’t panic – consider and communicate!

‘After the initial shock, the most important thing, I think, is to go back to your business plan and ask questions about whether your business plan is robust and whether that was the reasoning behind your loss of funding, or whether there’s a bigger strategy on the part of the funding bodies,’ says Jeremy Gaden, Director, The Substation.

‘My feeling is, from an organisational perspective, strong business plans will attract funding, whether that is from your state funding body or other sources; the most important thing is to have that business case. So when your funding does go missing or is cut, if you feel like your business case is strong, there are many other opportunities to seek funding outside of the state system.’

Gaden also believes it’s important to discuss your situation with funding bodies and other artists and arts organisations, for two reasons: ‘One, the broader sector needs to know the impact of decisions that funding bodies make. As an industry, as a sector, we need to be able to respond to decisions that funding bodies are making, so I think it is important to make your voice heard. And the second point is that there’s a lot of support to be had from your peers.

Certainly in the case of The Substation, when we didn’t receive funding in the last arts round, by us making that known to the sector we’ve had a number of partnership opportunities that have come our way since then, because other arts organisations have seen opportunities for them to help us survive through the non-funding period.’

Get feedback on your application.

Every artist and arts organisation is different, as are the reasons why their funding may be curtailed, or even withdrawn completely. Nonetheless, once piece of advice holds true for all: seek feedback on your application.

In the words of Heidi Victoria, the Victorian Minister for the Arts (2013): ‘The only downside of being the arts capital is that Arts Victoria consistently receives more quality applications than can be supported. For this reason, artists and organisations should not make any financial commitments on the expectation that a grant application will be recommended.

‘Any Victorian artist or organisation that has had an unsuccessful grant application in one program should not lose heart. As a first step they should seek feedback. This can be provided over the phone or through a meeting with program staff. The feedback process is an important step, it can outline why the application was not supported, as well as the other avenues that are available, and can ensure that future grant applications are more competitive.’

The same holds true for every state: by making sure you receive a detailed and clearly articulated response from the funding body in question, you ensure a greater chance of success in the next round.

Strategise and seek funding from other sources.

A failure to secure government funding isn’t the end of the world, as evidenced by the success of Pozible campaigns mounted by the Melbourne Cabaret Festival and the Queensland Literary Awards.

But whether you’re seeking to crowd-source funding via Pozible or some other platform, it’s important to have a considered, long-term vision for what you want to achieve, says Claire Booth, Manager, Queensland Literary Awards.

‘I think getting community support is number one; it doesn’t matter whether you’re looking for donations or corporate support, ensuring that what you do is positively communicated to the media, and positively communicated to the community, and getting a community of support is really important. That’s the first thing,’ Booth says.

‘Then, in our case, we established a committee quite early and developed a strategy from that; a communications strategy around how and what we wanted to communicate, and how we would communicate to the community. So in doing that, we knew that we needed to raise money, and we thought that Pozible, for our case, would be the most ideal. It wouldn’t always be the case, I don’t think – Pozible is just one platform, and it may not always work for everybody.

Read: 50 ways to survive lost funding – Madeleine Dore (2016)

‘But we didn’t go alone. We actually had corporate support last year from the Copyright Agency already. We felt there was a good match with what we do and the Copyright Agency, and they do support awards, but only awards that have a national coverage; so we knew that and we worked hard to get that support. And from there, we could leverage our support out to Pozible … and we then were able to progress this year in securing quite a significant number of sponsors, and going back to the Copyright Agency again for a grant. We got five other cash sponsors and we also enlisted the support of the State Library as an in-kind partner.

‘You have to start small, and you have to think: where might I seek support that best suits what I’m trying to do, and what we’re trying to achieve strategically? Not going scattergun to everybody,’ Booth concluded.

Downscale and diversify.

Just because funding for a project hasn’t come through doesn’t mean it’s dead in the water. Can it be scaled back to make it less expensive; or delayed, in order to reapply for funding or while you seek support from another quarter?

Diversifying your funding sources is particularly important given the changing cultural landcape, according to Paul Gurney, Executive Director and co-CEO of Next Wave.

‘It is important for not-for-profit arts organisations in Australia to identify a diverse range of funding options at the planning stage to ensure the organisation or project is not overly dependent on one source of income,’ he explains.

‘The Australian arts sector is experiencing a changing landscape of funding for the arts; a growing philanthropic community, Crowdfunding platforms and social enterprise all hold the potential to create new models that support the arts. In many ways, traditional not-for-profit business strategies are being challenged, and artists and arts managers require a more entrepreneurial approach to fundraising.’

Take drastic action.

Sometimes, a loss of funding can be a wake-up call; a chance for a company to urgently re-consider its core business, and drastically reshape itself as a result. Such was certainly the case for Melbourne’s Polyglot Theatre (then known as Polyglot Puppet Theatre) when it lost its Australia Council funding in 2008.

‘Sue [Giles, the company’s Artistic Director] and I made the decision that our story was not going to be one of disappointment and downsizing. We decided that our story was going to be about success against the odds; we were very definite in our knowledge and decision that that was going to be our approach and that would need drastic action,’ says Simon Abrahams, who was Polyglot’s Executive Producer at the time.

‘One, famously, was the shift around what at that point had been Polyglot Puppet Theatre to Polyglot Theatre. We reconceptualised the artistic vision of the company, which was also about the market vision of the company both nationally and internationally. We really identified what our core business and core strengths were, and they were … around this notion of interactivity and artistic play-spaces and large scale interactive work – which Polyglot had actually already been doing.

‘We Built This City for example is a work from 2001. It was really around saying “This is undoubtedly something that the organisation does very, very well that no-one else is doing”. There were other puppet theatre companies, and there still are, but no-one in this turf.’

As well as refocusing the company’s core business, Polyglot also closed down its venue as a space for hire.

‘We did make a bit of money out of it, but I just maintained that it was not core business for the organisation; that if we’re a theatre-making organisation we should be ploughing all our resources into doing that thing absolutely brilliantly rather than trying to do too many things not very well,’ says Abrahams.

The company also accelerated its plans for international touring, which not only increased its revenue stream but also helped raise Polyglot’s national profile; and rather than cutting its staff numbers, actually increased them. hiring a development manager.

‘People say to me all the time, “Losing funding was the best thing that ever happened to Polyglot,” and I kind of want to slap them in the face, because it makes it sound very easy, but it was also an incredibly devastating thing to happen. A lot of the decisions we made I suspect were things we would have done anyway – in fact they were things we had put in our business plan that at the time was rejected by the Australia Council … It is true that it made us reconsider things that otherwise we may not have done, but also I do like to think that had we had that funding right from the start, look at what we achieved without it and imagine what we could have done with that funding.’

Read: How to thrive, not just survive, when your company is defunded – Richard Watts (2019)

Ultimately, Abrahams says, a funding crisis is ‘a chance to reconceive and reconsider who you are, what you do and how you fit in. It can be a tremendous opportunity, even though it feels like the walls are crashing in all around you. Try and find a positive spark amongst the terror. I know what it’s like, and we’ve lived through it,’ he laughs.

Go it alone.

When all else fails, DIY. Composer and lyricist Casey Bennetto, of Keating! fame, responded to our Facebook query about funding crises with the following:

‘What to do when you’re defunded,

ev’ry dream and plan is plundered,

balances and cheques are sundered –

laugh or cry? I’ve often wondered.

Here’s the only real solution:

Fund the thing in execution.

Don’t depend on prostitution

(governmental contribution).

It’s not a rule I follow, true.

Do as I say, not as I do.’

REMEMBER THESE MOMENTS?

- Morrison Government’s complete abandonment of the arts is shocking – Tony Burke (2020)

- 65 arts organisations lose funding from Australia Council – Deborah Stone (2016)

- Small-to-mediums struggle to survive Brandis raid – Ben Eltham (2015)

- Budget shock decimates Australia Council – Ben Eltham (2015)

- Arts cuts: Abbott Government takes us backwards – Ben Eltham (2014)