Seed – quick links

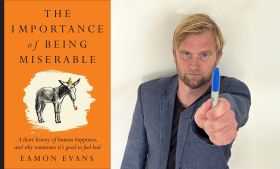

Can an end-of-the-world thriller have a happily ever after?

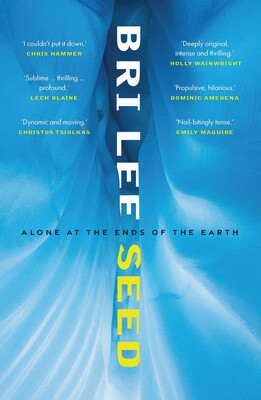

Bri Lee’s latest novel, Seed, follows just over a year after her debut fiction, The Work. While her first explored society and culture in populated cities of the world, Seed plunges the reader into the icy expanse of Antarctica, where questions of environment and human existence are pressed against a backdrop of white nothingness.

Mitchell is a celebrated biologist and co-founder of Antinatalism Australia Journal who travels south to Antarctica for one month each year where he joins ‘brilliant scientist’ Frances in a utopian experiment of radical equality working on the Anarctos Project – a hidden seed vault designed to safeguard biodiversity against humanity’s destruction of the planet.

Another member of the Anarctos project is Mitchell’s ex-wife Kate, the only pilot capable of flying a chopper to the vault location. Kate was also the co-founder with Mitch of Antinatalism Australia Journal, but that was before she chose to have a child with another colleague on the project.

As heavily pregnant Kate drops them off and returns to Australia, we stay with Mitch and Frances for a month of seed sampling, researching, surviving and sex.

Seed: utopia unravelling

Sex, a common thread in Lee’s fictional work, is not as graphic in this novel as in The Work, but more a necessity of nature for our main character. Mitchell doesn’t want kids but he wants sex every other day, and Frances seems amicable with the arrangement. What happens in Antarctica stays in Antarctica, right?

But the utopia starts to unravel, and it’s not when the blurb suggests. It all starts with an intruder at the camp – a cat.

Mitchell is convinced the cat is a gift from his ex-wife but with Anarctos strict policy of no children, no pets, would Kate really risk the entire project on this small gesture? Nevertheless, Mitchell persuades Frances to keep it.

The colleagues get into a rhythm, with more unsettling incidents – windows breaking, an unexplained seedling crate and the outage of radio communication – staining what is a month of bliss away from civilisation, where Mitchell spends most his time reminiscing about Kate, his ‘seed of hope’.

Seed: Black Mirror-like

It’s halfway through the novel when Kate fails to pick up Mitchell and Frances that things become Black Mirror-like. There’s an avalanche of action and stranger-than-fiction discoveries that you can’t stop reading until the final page.

Lee understands her audience and crafts an intellectually stimulating read that will both divide opinions and allow readers to engage in discussion. Conflicting views are not flaws in this novel, they are its very purpose.

Lee writes in shifting registers. At times, first-person reads like an explorer’s diary, similar to Robert Falcon Scott, the explorer who led two Antarctic expeditions, the second ill-fated, and is referenced throughout the novel. It forces readers to inhabit the mind of a man whose intellect is both a weapon and a wound.

At other times, the language goes much deeper, with moments of exquisite beauty. Descriptions of animal life and the sublime of aloneness remind us of the stakes of their project: ‘Once you have tasted the gloriousness of this abyss, it called to you ever after.’

Seed: testing for some

Yet Seed will be a testing read for some. Lee grants Mitchell such dominance of the page that his ruminations can sometimes weigh down the plot.

Readers may find themselves turning pages less for the fate of the characters and more for the fate of the planet itself.

ArtsHub: Best new books September 2025

There are also moments when logic falters. Would Frances, methodical as she is and more desire than Mitchell to return home, truly forget about the emergency radio at the pick-up point? Would she not anticipate every contingency?

Still, there is no denying Lee’s ambition, layering philosophy, climate science and politics without pandering. Weaving non-fiction themes into her fiction makes readers think differently. There are no happy endings here, and that’s the point.

The novel interrogates not only environmental collapse but also the seeds sown in childhood and how they shape adult choices: ‘If someone had sown the wrong seed in you when you were a child – shame, guilt, fear – no amount of adult intellect could till it out.’

Seed feels like a slow burn in the first half, but the final destination arrives quicker than anticipated, much like the pace of climate change itself.

Seed by Bri Lee is published by Simon & Schuster/ Summit Books on 30 September 2025.