One of Man Ray’s most celebrated photographs, Le violon d’Ingres, 1924, depicts the turban clad Kiki de Montparnasse, his lover and model in his early years in Paris. Sitting with her back to the viewer, Ray references the neoclassical painter Ingre and his devotion to the violin through the curves of de Montparnasse’s body.

Using the photogram process to make the violin sound holes, he illuminates the form with soft lighting on her back in contrast to a darkened background. It is playful in nature and an important departure from ways of presenting the nude in art.

Man Ray and Max Dupain: quick links

Man Ray and Max Dupain: breadth and experimentation

Represented in the exhibition Man Ray and Max Dupain, currently showing at Heide Museum of Modern Art, Ray’s iconic image sets the tone for this beautifully presented and weighty exploration into two important modernist artists of the 20th century. Dupain’s celebrated work, Sunbaker, c. 1938, that became synonymous with Australian beach culture however, is nowhere to be found.

Instead, the curators take us on a fascinating journey, exploring the breadth and experimentation of the artist’s work in a kind of creative dialogue through the Dadaist and Surrealist influences of Ray.

Curated by Emmanuelle de l’Ecotais, a Ray historian and Artistic Director of Photo Days, Paris and Lesley Harding, Artistic Director of Heide Museum of Modern Art, the exhibition features over 200 photographs from still life and nudes to portraits, fashion and advertising.

The works of Ray coming from largely private collections in Paris while the Dupain from various state collections from around Australia: all are gelatin silver prints and some are vintage images while others more recent reprints.

Man Ray and Max Dupain: women artists also in exhibition

Also represented in the exhibition are two important woman artists: Lee Miller and Olive Cotton, who were not just the models and lovers of these men but important artists in their own right and whose influence was paramount in the nascent development of both Ray and Dupain’s work.

Examples in the exhibition are Cotton’s gently humorous Tea Cup Ballet, c. 1935, in which she plays with dramatic light and shadow while Miller’s Self Portrait, c. 1930, draws on classical themes using finely modulated tone to create a sense of the sculptural.

Based in Paris, Ray (1890-1976) worked across art mediums but is perhaps best known for his innovative photography, which included techniques such as solarisation, achieved through the light being briefly turned on during darkroom development, creating anaura-like effect around the form.

In works such as Meret Oppenheim, 1932, the bold outline of the image is emphasised, while using light to flatten the face and soften the shadows of the neck and shoulder, giving the image a sketch-like quality, a technique he reworked with Lee Miller.

Man Ray and Max Dupain: pictorialism to modernism

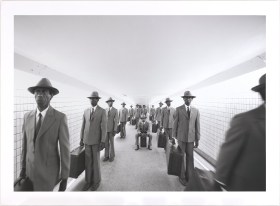

Transitioning from pictorialism to a modernist form of expression after coming across the book Photographs by Man Ray 1920-1934, Sydney photographer Dupain (1911-1992), explored and developed Surrealist ideas in works such as Still Life, 1935 in which the cropped torso of a woman, reduced to tonal elements of light and dark, is viewed through the play of light on a brandy glass.

Other works such as Ray’s Érotique voilée, 1933 from the series of the same name, playfully contrasts the mechanical wheel of the printing press with the female form and is an interesting juxtaposition to Dupain’s visual conundrums such as Brave New World, 1935 and Homage to D. H. Lawrence, 1937, in which the artist makes montage overlays with reference to the modernist notion of the mechanistic as well as drawing on classical and futuristic ideals.

Delineating gallery spaces through wall colour provides visual contrast within the larger rooms while also suggesting a change in theme or focus whilst the interior ‘fit out’ of these spaces with angled walls and mirrors playing effectively on the fractured, surreal nature of many of the images on display.

Man Ray and Max Dupain: darkroom context

A smaller space, painted black takes the viewer into the darkroom context in which both Ray and Dupain experimented with photograms or the ‘camera-less’ photographs, Ray later coining the term ‘rayographs’, a technique which involved placing objects on top of photosensitive paper and then exposing the paper briefly to light.

Honouring Ray’s work in this field, Dupain titled some of his prints ‘rayographs’ as well as developing his own style by incorporating figurative imagery and organic elements such as water into his photograms . This form of artmaking allowed for the element of chance and spontaneity as well as challenging notions of visual perception apparent in both Dadaist ideas and Surrealism; a playful hanging of the works echoing the theme.

Forays into the moving image, such as Emak Bakia, 1926 a 16mm, 19 minute film (shown in the exhibition) further reflect Ray’s Dadaist sense of the absurd and his experimentation with the rayograph technique.

Although the exhibition is well support by display cabinets of contextual material and didactic panels, the grouping of the images and corresponding text labels may be a little confusing for some viewers when deciphering individual works by the artists.

Man Ray and Max Dupain: public programs and catalogue included

The exhibition is also supported by a number of public programs and an impressive catalogue featuring essays by the curators alongside texts by Tamara Abramovitch, Judy Annear, Lana De Lorenze, Helen Ennis, Shaune Lakin, Gael Newton, Antony Penrose and Susan van Wyk.

Read: Would That It Were a Fortress review: June Jones EP is a chrysalis

This finely curated exhibition is large but well worth the time and effort to explore a fascinating visual conversation over time and continents between two of the 20th centuries great modernist photographers.

The works of Man Ray and Max Dupain will be exhibited at Heide Museum of Modern Art in Victoria until 9 November 2025.