The Djilba/Kambarang season at Perth Institute of Contemporary Art (PICA) features exhibitions by three artists exploring connections to history, inheritance and women’s authorship. The exhibitions are Duilian by Wu Tsang, This Creature by Sriwhana Spong and ām / ammā / mā maram by Sancintya Mohini Simpson. This season also marks the launch of the inaugural work for the Judy Wheeler commission, Roost by Elizabeth Willing.

A single 30-minute video work surrounded by an ocean of red curtains, Tsang’s Duilian is a mythical retelling of the queer relationship between Qiu Jin, a famous feminist who inspired revolutionary movements against the Qin empire in the early 20th century, and her lover Wu Zhiying.

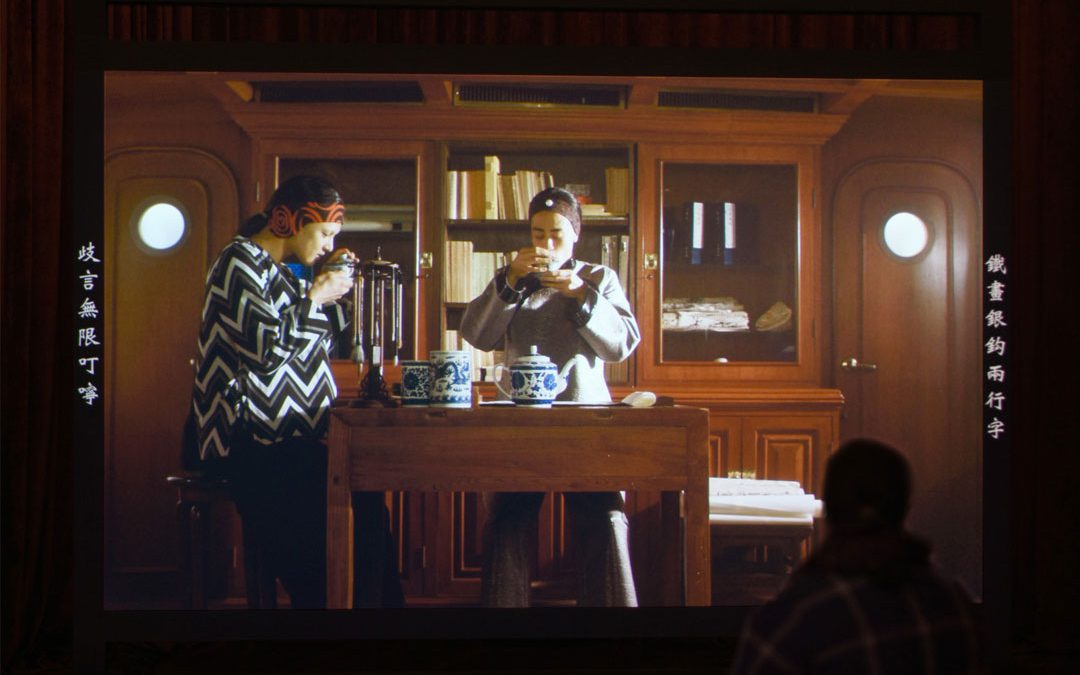

The grandiosity of this installation in PICA is mirrored in the cinematic production of the video itself, which includes dreamy shots of Hong Kong’s Victoria Harbour at dusk, martial arts choreography from female Wushu masters and a tête-à-tête on a junk boat between Qiu Jin and Wu Zhiying, played by Wu Tsang and her artistic collaborator boychild respectively. Some of the dialogue comes from fragments of letters and Qiu Jin’s poetry translated into various languages, including Tagalog, Bahasa Indonesian, Iloco, Cantonese and Mandarin.

Several of the translations were the first translations of Qiu Jin’s poems. The title Duilian refers to a Chinese poetic form where two lines are paired together like musical counterpoints, highlighting the playful tension of contrary opinions between the two historical lovers, and the tension between queer and Asian identities in a diaspora and on the mainland.

Spong’s This Creature is a 15-minute video work filmed on her iPhone and displayed in a small nook on the second floor of the gallery. The film shows Spong’s hands touching various buildings, walls and sculptures in Hyde Park, London while reading out an email exchange between her and the British Library. In the email, she asks for access to the physical copy of Margery Kempe’s This Creature, considered the first autobiography in the English language.

Like Tsang’s work, here there is a playful delight in the interweaving of intimate correspondence and public expression. The juxtaposition of these two exhibitions, each consisting of single works of film, meaningfully explores the notion of women being entitled to own a history and an inheritance, and to communicate this through poetry and embodiment. These are narratives of resistance that simultaneously explore identities beyond binary notions of gender and culture.

On the upper level of PICA in a room filled with natural light is Simpson’s ām / ammā / mā maram, the Brisbane-based artist’s first exhibition in Western Australia. The light creates a restful and contemplative atmosphere. Simpson deftly moves between different artistic mediums in her exploration of her matrilineal heritage as a descendent of indentured labourers from India, who were sent to work on colonial sugar plantations in South Africa throughout the period 1834-1971. This history is both material and poetic.

On the gallery wall is the only known photograph of Simpson’s great-grandmother and great-great-grandmother in Durban, Natal, South Africa. On the opposite wall hangs a poem written with pigment made from sugarcane ash on paper made from mango bark. It reads: ‘Remnants/of my ancestors/arrive in packages/sent by strangers, found/on late night eBay searches.’ Simpson has also drawn a kolam at the beginning and end of the poem, a traditional decorative art with ancient roots.

In contrast to the play with fiction and identity of the other two exhibitions, Simpson’s exhibition feels grounded in the experience of learning/unlearning of diasporic identity through conversations with her mother and matrilineal heritage. The title consists of the words “mango” in Hindi, “mother” in many languages throughout South Asia and “mango tree” in Tamil.

All three exhibitions explore this notion of the historical self that lives in all of us – from within which we emerge and inherit a history. Through their work, these artists configure new relationships to the past through an inheritance of women’s authorship.

In addition, this season marks the launch of the inaugural Judy Wheeler commission, a 10-year site-specific commission thematically centred on PICA’s physical location. Elizabeth Willing’s print work Roost uses Kipfler potatoes as print blocks to create a visceral undulating pattern. On the border of the work Willing has written various smells of the hospitality businesses in the surrounding suburbs of PICA – “Coffee” “Rosemary” “Car Exhaust” “Candle Wax”. The work Roost itself smells faintly of wood and starch, evoking the settler history of migration and settlement in Northbridge.

PICA’s Djilba/Kambarang season program runs from 4 August to 22 October; free.

This review is published under the Amplify Collective, an initiative supported by The Walkley Foundation and made possible through funding from the Meta Australian News Fund.