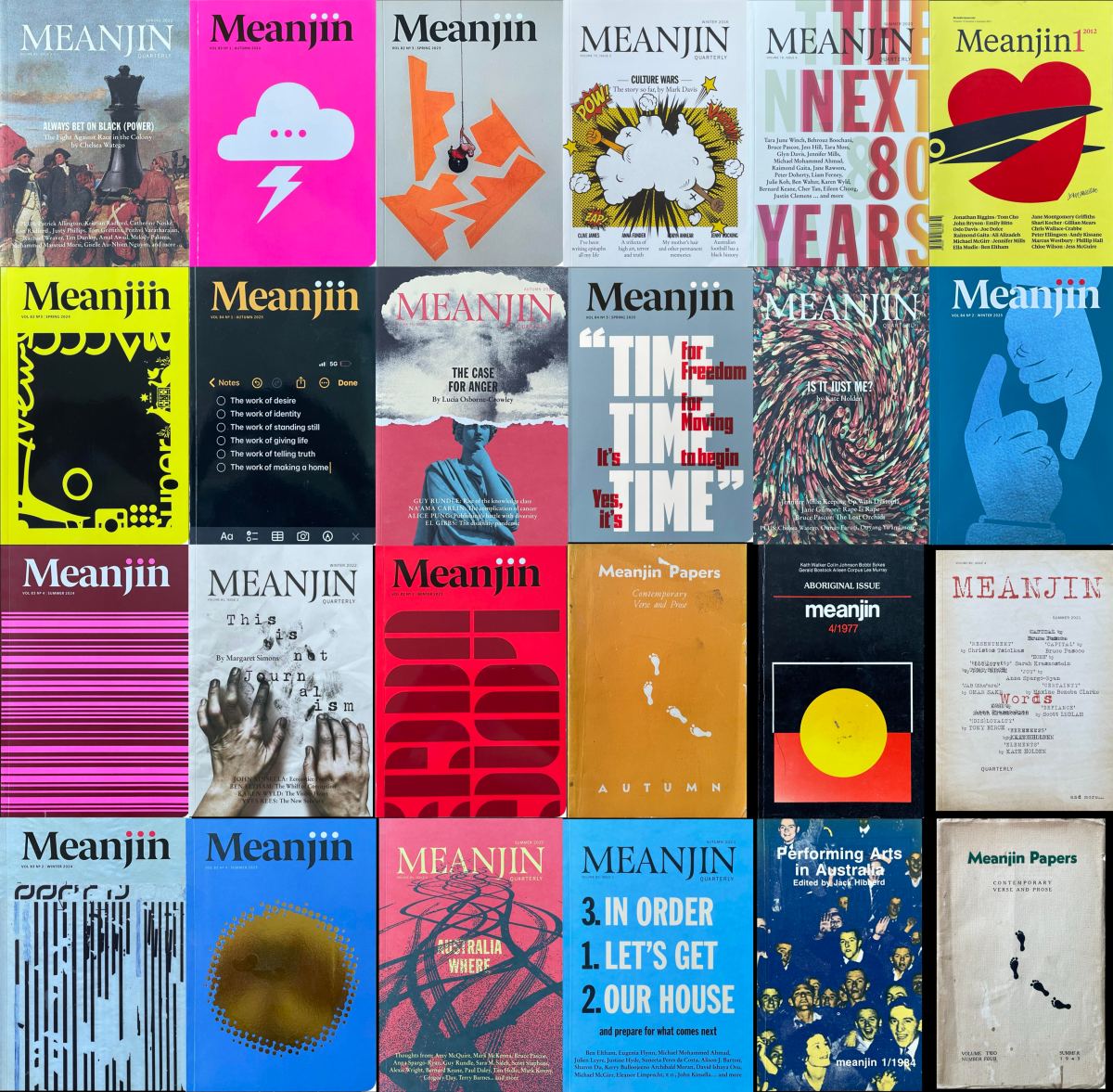

Until very recently, I was the Archives Editor at Meanjin, overseeing an 85-year-old repository of Australia’s finest writing with no expectations that it would all end there.

Melbourne University Publishing’s decision to shut down Meanjin in September came as a shock to many, but arguably none more than the journal’s staff, who learnt that their services were no longer needed through a news headline.

At this time there were supporting editors, technical professionals and an advisory board collaborating with the principal editors, Esther Anatolitis and Eli McLean, to produce Meanjin in both quarterly and daily forms. It was one of the country’s most culturally diverse and disability representative publishing teams.

It took more than an hour after the story broke, and was covered by several mastheads, to receive official notice from MUP; a group email confirming Meanjin’s immediate closure.

Their statement reduced Anatolitis and McLean to the description of ‘two part-time staff’. All other dedicated staff were overlooked. Of course, it is now common knowledge that the decision was said to have been made on ‘purely financial grounds,’ and was a matter of ‘deep regret’ for the publisher.

One struggled to locate the sincerity or be convinced by the arguments.

Meanjin: plans in progress

It was a baffling situation to say the least. We still had two quarterly editions coming out this year, one of which to celebrate the journal’s 85th birthday – an occasion for reflecting on its storied past and anticipating next steps. There were projects underway and future plans in place. In my case, I had a daily newsletter primed for subscribers’ inboxes the following day.

Surely we could consult our editors? Be given time to complete assignments? Have an opportunity to thank readers? Retire with dignity as one of Australia’s oldest and most respected publications? No. It was made clear that this would be a hasty exit with little explanation as to why. A month later, questions remain unanswered.

There have been claims that subscriptions were declining, though the deputy editor has disputed this on the record. The fact is that readership was on the rise. As Archives Editor, I witnessed healthy reader engagement on a daily basis. While paid subscriptions for hard copies of the quarterly may have decreased, our readership was reaching meaningful new heights, especially among emerging and minority writers whose perspectives were intrinsic to the Meanjin ethos.

Conflating revenue with readership distorts our understanding of cultural value.

To explain further. On the day of the closure, MUP promptly logged me out of the newsletter platform used to greet subscribers every morning with a relic from Meanjin’s vast and varied archive collection. Through this free daily reading initiative, which had commenced during Melbourne’s lockdowns, I prepared and (re)introduced thousands of articles to a loyal following of enthusiasts. Poetry, essays, memoir, fiction, interviews, playscripts and book reviews from over eight decades illuminated Meanjin’s centrality to formative cultural discourses.

The daily readings traced Meanjin’s trajectory from 1940 to the present, allowing history to reveal and revise itself through the country’s literary output. These archives put Australia’s writerly prowess on full display while reflecting a national identity in flux as it confronted world wars, colonisation, political upheaval, ideological division and technological expansion. Meanjin had withstood this tumult while navigating lifelong funding pressures.

The archives captured striking moments in time: Henry Handel Richardson demanding she be called by her chosen male name; Oodgeroo Noonuccal charting the course of poetic activism against colonial injustice; Patrick White urging cultural reform with a vote for Gough Whitlam; Helen Garner challenging sceptics of first-person expression.

We also revisited writing from Alexis Wright, Tim Winton, Miles Franklin, Tony Birch, Alice Pung, Lisa Bellear, Christina Stead, Ouyang Yu, Robin Boyd, Antigone Kefala and even a teenage Rupert Murdoch, in which he confessed to being ‘a little nervous’ about the prospect of editing others’ words. There were hundreds, if not thousands, of articles still to resurface.

Parallels with today were often uncanny. When attitudes didn’t sit well, it clarified progress.

Meanjin: the warmth of readers

One of the joys of embarking on this project was the warmth with which it was received by so many readers. The newsletter made accessing cultural history an inclusive practice. We had a wide subscriber base from around Australia and overseas that included MPs, students, health practitioners, authors, designers and vice-chancellors.

It was special when former contributors signed up to experience their writing in a new context. One faithful subscriber was a distinguished nonagenarian poet whose work was first printed in Meanjin in the 1950s. Connections like these cannot be quantified.

More recently, I extended Meanjin’s archive engagement to social media, introducing Instagram users to the collection with a daily post. It was an effective way to interact with different readers, and mark events such as NAIDOC and Reconciliation Weeks.

The follower count jumped, drawing attention from creative organisations both locally and abroad. In a thrilling counter to scroll culture, people paused to click the ‘link in bio’ and read more. It felt like we were just getting started.

MUP were quick to log me out of this platform too. When they changed the password, they also disabled the comments function so followers could not respond. They have since posted twice from Meanjin’s social media, but it is MUP speaking. Meanjin has no control over its digital legacy.

The archives are now in MUP’s hands. We can only hope they bring the careful curation and insights of the Meanjin staff so abruptly dismissed.

With my unique perspective of having read everything in Meanjin, from its first edition to the last, I mourn the journal’s lost opportunities. To quote poet Mary Gilmore from the summer edition of 1960:

Life leaves no mark on time;

But memory has given us words.

Words are the steps by which we climb.

Emma Sutherland was the Meanjin Archives Editor.

Read more on ArtsHub: