For years, selling more drinks at interval has been seen as a guaranteed way to raise revenue for venues. But the travails of the Arts Centre in Melbourne show that making money from hospitality is no easy feat.

As ArtsHub reported last month in Spiegeltent gone, jobs axed the Arts Centre, Melbourne’s premier performing arts institution, faces a massive budget blow-out. Redundancies will follow: entire programming departments are to be abolished as the Arts Centre faces an estimated $8 million overrun.

The red ink has been flowing for some time. The Centre’s 2012 annual report recorded a $14 million dollar operating loss. With revenues of $60 million and expenses of $74 million last year, the Arts Centre’s financial problems are clearly more serious than just a few dud shows – although, it can’t help that Einstein on the Beach was budgeted to lose $1 million during its run.

One of the Arts Centre’s biggest problems was not detailed in the 2012 Annual Report. This was the decision by the Arts Centre to bring much of its catering and hospitality “in-house” – in other words, to replace the existing tenants providing food and beverages at the Arts Centre.

The idea, as explained in the Annual Report by Arts Centre CEO Judith Isherwood, was “a complex task which was successfully handled by the Visitor Businesses unit despite the added pressures of the concurrent Hamer Hall re-opening.” The Arts Centre hoped to run these bars and cafes at a profit, and return the funds to putting on shows, “as profits flow towards programming our stages rather than to an external operator.”

Unfortunately, ArtsHub understands there haven’t been any profits flowing towards programming. In fact, the move has caused disastrous losses, with patrons shunning the Arts Centre’s new food and beverage arrangements. As someone who recently had the misfortune to munch on a tiny and tasteless sandwich for $7 at the Arts Centre, I can understand why. The Melbourne CBD contains no shortage of competing food and drink options, so it’s hardly surprising if patrons opt to eat and drink elsewhere.

Previously, the Centre had earned a handsome revenue stream from the private sector operators, who had paid the Centre a rent for the privilege of serving a captive audience.

After moving to bring food in-house, the Centre quickly found itself in the red. Big new upfront costs had not been anticipated, as new catering equipment had to be purchased. Nor was the Arts Centre able to manage the razor-thin margins typical of a hospitality business. The forthcoming financial results, due to be tabled to Parliament on October 15, are expected to detail the bloodbath.

The Arts Centre’s hospitality problems have some unique features. ArtsHub understands that the lease for the various cafes and bars came up suddenly, forcing the Centre to make a quick decision about what to do. The Centre could have searched for new tenants. But with government grants cut by 3.5 per cent in a Baillieu government austerity drive, the temptation to chase revenue growth must have been strong. Once the lease was given up, the Arts Centre was then faced with the daunting task of starting a brand new hospitality business from scratch.

Macroeconomic issues are also at play. The general moderation in consumer spending in recent years has resulted in plenty of pain in the retail, arts and recreation sectors. For instance, there has been a dramatic shake-out in once-booming contemporary music festivals. A few years ago, music festivals were going gangbusters, with new events proliferating across the country. But the salad days are over, with a number of high profile events shutting down. A.J. Maddah’s Harvest Festival called stumps this year, and the Big Day Out is putting on only one date in Sydney, for the first time in years.

It’s difficult to determine to what degree these broader factors have fed into the Arts Centre’s problems, but we do know that ticket sales have been down at several of the big performing arts venues around the country. Smaller box offices also mean fewer patrons at interval, and fewer customers for Arts Centre chardonnays and sandwiches. It’s something of a vicious cycle.

The travails of the Arts Centre may be quite particular, but they do raise some uncomfortable issues for the broader arts industry. For years, selling more drinks at interval has been seen as a guaranteed way to raise revenue for performing arts venues and companies. But, as any bar manager or café owner can tell you, making money from hospitality is no mean feat. High staff costs and volatile turnover makes it an industry where start-ups regularly fail, and even hardy veterans struggle to survive.

Michael Porter’s famous “five forces” model of industry competitiveness shows why hospitality revenue is not necessarily the magic bullet that arts managers often assume. Porter’s forces include factors such as inter-industry competitiveness, the threat of new entrants or product substitutes, and the bargaining power of customers and suppliers. As Porter explains in the Harvard Business Review, “industry structure drives competition and profitability.”

Above: Michael Porter’s “five forces” model of industry competition. Source: Harvard Business Review.

If we think about performing arts venues from a five forces viewpoint, it’s easy to see why making a buck is difficult. In a nutshell, competitive forces are fierce. Suppliers (in other words, the talent) often have considerable bargaining power, with a plethora of venues competing for their business. Customers have never been more spoilt for choice when it comes for ways to spend a night out. Venues are also under threat from substitution, with art lovers able to get their fix from the internet, and there is a constant stream of new entrants to the industry in the form of small venues and one-off festivals and events.

Strategy and management are two different things. Even if the strategy is right, the execution could be flawed. It should, in theory, be eminently possible to make money from selling drinks at a performing arts venue. But if the cost structures aren’t right, even a captive audience can’t guarantee profits. For the managers of arts venues looking for ways to become more sustainable, there are no easy answers.

Of course, there is one thing that could quickly revive a venue’s fortunes: a run of hit shows. Perhaps that’s what the Arts Centre should concentrate on, leaving the nitty gritty of selling food and drinks to people who know what they’re doing.

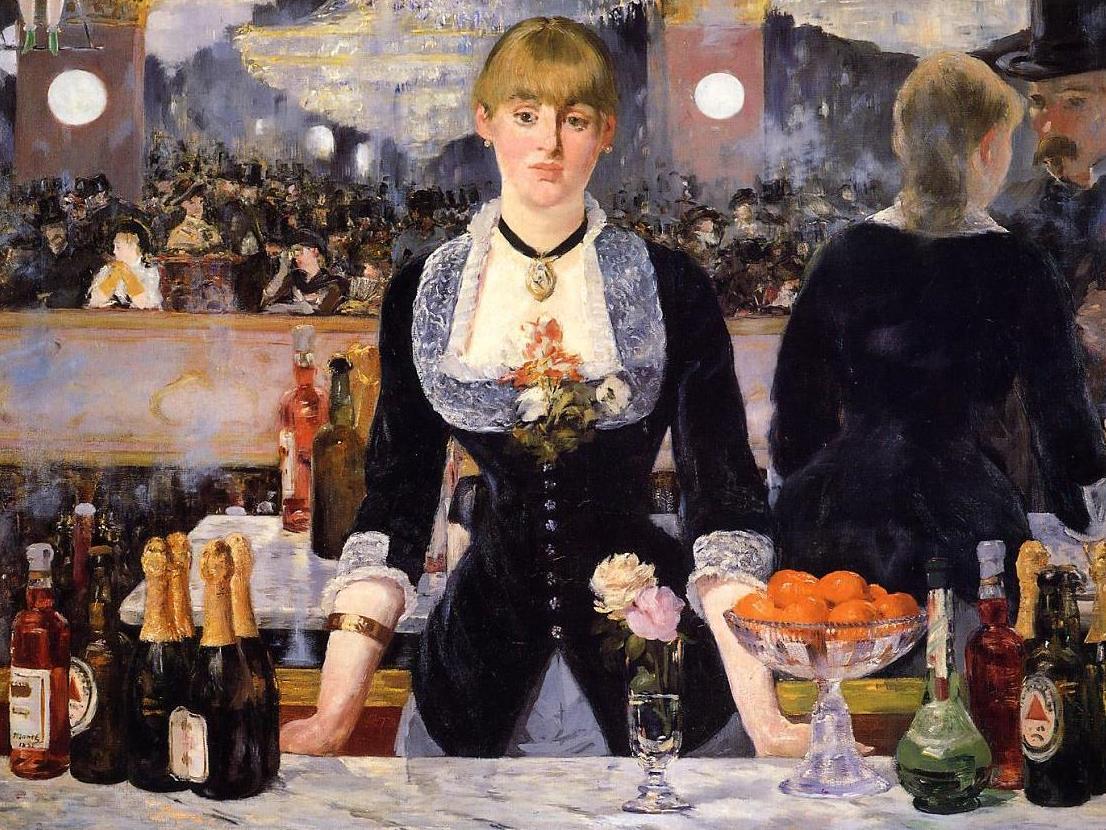

Image: Edouard Manet, A Bar at the Folies-Bergere, 1882