Gloria, Queensland Theatre Company. Image: qldtheatreco.com.au

In October 1994 the then Prime Minister Paul Keating unveiled the first ever national cultural policy, called Creative Nation. It was heralded as a major achievement, providing an additional $250 million in funding and a broad approach to supporting the arts and artists through a huge range of activities.

This cultural policy is also an economic policy. Culture creates wealth. Broadly defined, our cultural industries generate 13 billion dollars a year. Culture employs. Around 336,000 Australians are employed in culture-related industries. Culture adds value, it makes an essential contribution to innovation, marketing and design. It is a badge of our industry. The level of our creativity substantially determines our ability to adapt to new economic imperatives. It is a valuable export in itself and an essential accompaniment to the export of other commodities. It attracts tourists and students. It is essential to our economic success.

It was developed with support from a specially convened Cultural Policy Advisory Panel comprised of filmmaker Gillian Armstrong AM, novelist Thea Astley AO, novelist Rodney Hall, designer Jennifer Kee, ABC broadcaster Jill Kitson, Indigenous teacher and performer Michael Leslie, choreographer Graeme Murphy AM, cartoonist Bruce Petty, arts czar Leo Schofield AM and academic Peter Spearritt. In their day an array of luminaries from a range of disciplines and easily regarded as cultural leaders. They created a Charter of Cultural Rights and pursued the idea of a Ministry of Culture and the promotion of culture to Cabinet level representation.

Charter of Cultural Rights

We recommend the Government’s commitment to a charter of `Cultural Rights’ that guarantees all Australians:

• the right to an education that develops individual creativity and appreciation of the creativity of others;• the right of access to our intellectual and cultural heritage;

• the right to new intellectual and artistic works; and

• the right to community participation in cultural and intellectual life.

Amazing words. But wait there’s more . . .

It is time for government to elevate culture on the political agenda, to recognise that it has a natural place in the expectations of all Australians. In the light of this, it is important to assert that:

• culture is the expression of a society’s aesthetic, moral and spiritual values, indeed of its understanding of the world and of life itself;

• culture transmits the heritage of the past and creates the heritage of the future;

• culture is a measure of civilisation, at its best, enhancing and ennobling human existence; and

• in the Australian context, implicit in our use of the word `culture’ is the value we attach to expressions of a recognisably Australian `spirit’.

And more. The Prime Minister said on 10 July 1992:

The Commonwealth’s responsibility to maintain and develop Australian culture means, among many other things, that on a national level;

• innovation and ideas are perpetually encouraged;

• self-expression and creativity are encouraged;

• our heritage is preserved as more develops; and

• all Australians have a chance to participate and receive — that we invigorate the national life and return its product to the people.

The document spells out policy after policy, funding promise after funding promise. It is like a Christmas gift to the country and even now is the most comprehensive commitment to the arts and culture sectors I have read. It is worth reading just to relive the excitement we all felt twenty years ago. It was exhilarating.

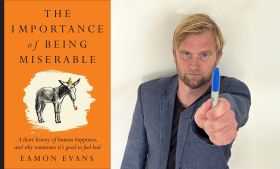

Wesley Enoch. Image: supplied

But this was to come to nought with the change of government in 1996. John Howard brought us an era of being ‘relaxed and comfortable’ and we saw many of these developments either disappear or be wound back as the ‘Beazley black hole’ swallowed the arts. The Major Performing Arts companies were protected from many of these cuts and in 1999 the Nugent Report secured their future with a series of fixed contracts between the states and the Australia Council.

It took nearly twenty years before we saw the next National Cultural Policy, launched in March 2013, imaginatively named Creative Australia. It was based on wide consultation, came with little if any ‘new’ money but highlighted some more values and principles to mark the way forward.

This policy has five overarching goals, developed in close consultation with the community it serves. These goals articulate the future this policy will enable: the centrality of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander cultures; the diversity of Australia and the right of citizens to shape cultural identity; the central role of the artist; the contribution of culture to national life and the economy; innovation and a digitally enabled creative Australia.

Goal 1

Recognise, respect and celebrate the centrality of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander cultures to the uniqueness of Australian identity.

Goal 2

Ensure that government support reflects the diversity of Australia and that all citizens, wherever they live, whatever their background or circumstances, have a right to shape our cultural identity and its expression.

Goal 3

Support excellence and the special role of artists and their creative collaborators as the source of original work and ideas, including telling Australian stories.

Goal 4

Strengthen the capacity of the cultural sector to contribute to national life, community wellbeing and the economy.

Goal 5

Ensure Australian creativity thrives here and abroad in the digitally enabled twenty-first century, by supporting innovation, the development of new creative content, knowledge and creative industries.

This policy had far less fanfare than its 1994 cousin as the Labor Government rocked with internal disputes. Arts Minister Simon Crean, the major architect of Creative Australia, found himself on the backbench after calling for a leadership challenge; and the policy found the bottom of a bin when the 7 September 2013 election swept Tony Abbott and the Liberal-National Coalition into power.

In his article for the Guardian at the time Ben Eltham wrote hopefully,

2013 might be one of the better elections in terms of the arts and culture of many years, with Labor, Liberal and the Greens making positive statements and little sign of the culture wars of the Howard years.

As we now know the 2014 federal budget saw cuts to many of the arts and cultural instrumentalities including the Australia Council, ABC, SBS and Screen Australia. But Ray Gill in the Daily Review on Crikey.com warned:

Where the Australia Council makes its cuts is yet to be determined [. . .] but the arts companies most able to absorb cost cutting are spared. Our 28 major arts companies that include Opera Australia, the Australian Ballet and the major state theatre companies and orchestras don’t take the cuts. They account for about 65 per cent of the Australia Council annual grants and they are locked into untouchable three-year contracts. The choices left for the Australia Council are to make cuts within its own organisation; to cut individual and project grants which will affect small to medium arts; or do both.

Are governments, therefore, the cultural leaders we are looking for? I doubt it. When it comes to government leadership we find ourselves locked into a disabling flip-flop run on political ideology, ambition and fashion. There seem to be very few policy frameworks that don’t come from government and they are all vulnerable to the vagaries of election campaigns and changes of government. Any hope for multilateral recognition of the centrality of the arts and cultural spheres seems doomed. Some things that are too important to play politics with—education, health, and I suggest the arts. Cultural leadership needs to be given by those who have skin in the game, who can pilot their way through the complex ethical and social issues. Government, by its very nature, is mired in politics and point scoring. The intention behind having a Ministry of Culture, as suggested by the Creative Nation Policy Advisory Panel, was to deliver security to the arts; but all it did was paint a target on our backs.

This is an edited excerpt of Wesley’s Enoch’s new Platform Paper for Currency House, Take Me To Your Leader: The dilemma of cultural leadership, now available on https://currencyhouse.org.au/

This is the 10th anniversary of Platform Papers.