‘When we read stories in the media around disability, sometimes they haven’t spoken to disabled people,’ Carly Findlay told Artshub. As a writer, editor and appearance activist, Findlay has her own experiences of ableism bust as editor of Growing up Disabled in Australia she has insights from 46 contributors.

For this episode of the ArtsHubbub, Findlay spoke with ArtsHub’s Performing Arts Editor Richard Watts about the importance of the book, setting media guidelines for how we report on disability and the importance of language.

‘It’s really important that it is own-voices led and disability led and the idea of ‘nothing about us without us’ is really important,’ Findlay said.

‘When we read stories in the media around disability, sometimes they haven’t spoken to disabled people,’ Findlay states.

‘I always look at the rate of media reporting on ichthyosis, the skin condition I have, and it’s terribly reported on, really sensationalised, particularly when parents talk about their children as burdens or scary. And, of course, when a parent says that they love their child, but they also say to a journalist, “well, having a child with a disability is worse than having a child with cancer,” of course, the media is going to pick up on the negative connotation and that’s gonna get sensationalised. So yeah, it is really important that our voices are centred because so often they’re not.’

To coincide with the book’s release, Findlay developed a set of media guidelines to ensure journalists and reviewers could discuss the work in a way that used correct language when talking about disability.

‘People are scared of doing the wrong thing and saying the wrong thing around disability, non-disabled people, even disabled people,’ she said.

‘So I really wanted to prepare journalists to report on this fairly and not to see us as objects of pity or inspiration. I wanted them to use the correct language and not ask inappropriate questions. Because I mean, I’ve had some really awful experiences in the media and I didn’t want the contributors to have that either. ‘

I really wanted to prepare journalists to report on this fairly and not to see us as objects of pity or inspiration. I wanted them to use the correct language and not ask inappropriate questions.

– Carly Findlay

The book also makes readers think about the word disability, its connotations and the way it has been embraced by some of the writers featured in the book, including Findlay.

‘It took me a long time to call myself disabled or a person with disability at the time, because I didn’t see anyone looking like me,’ she said.

‘We really need to see that disability comes in lots of ways and lots of experiences, and it doesn’t just look a certain way. And that, yes, someone with a skin condition could consider themselves as disabled; someone who is neurodiverse might not yet be ready to call themselves disabled yet’

Findlay says she hopes the book will help non-disabled people think more carefully about what they say. Often they have good intentions but their meaning can be misconstrued.

‘I really want to show that disability isn’t something to be pitied or tragic. It’s not always sad, and not always discriminatory.’

Listen to the latest episode of The ArtsHubbub on your favourite podcast platform.

EPISODE TRANSCRIPT:

[Theme music]

George Dunford: Welcome to the ArtsHubbub, a monthly look inside Australian arts – and artists. I’m your host, George Dunford.

This month we’re looking at how the arts can become more accessible by speaking with someone who brings a lived experience of disability to her art, and activism.

Carly Findlay: It took me a long time to call myself disabled or a person with disability at the time, because I didn’t see anyone looking like me. And I didn’t think that the things I needed at school were the same as the things that someone else with the more severe disability needed.

And so it wasn’t until I started like, meeting people – when I mentored at the hospital – with different chronic illnesses, and we all had the same kind of external barriers, the disabling barriers, we had very similar experiences with doctors, with hospitals, with time off school, with bullying, with discrimination. And so then I’m like, Oh, wow, I you know, I obviously have a long, lifelong skin condition that, which is a chronic illness, it makes me very sick. And it’s okay for me to call that.. you know, term myself that.

GD: That’s Carly Findlay OAM, an Australian writer, speaker and appearance activist, who lives with a genetic skin condition, ichthyosis. Carly talks about her experience in her 2019 memoir, Say Hello, which fosters disability pride – while addressing negative attitudes and preconceptions about disabled people. When she started doing public appearances and media for the book she found new challenges to her advocacy.

CF:A man bought my book and I was just so excited, and I was signing it, but then a woman came up and interrupted me and she says, Oh, honey, when you open your mouth to speak, I don’t even notice your face. Like, what? Like, she meant that as a compliment but it was so insensitive, because I was talking about the need to be seen and being visible through fashion and activism. And she just completely erased all of that.

GD: Activism has long been an important part of Carly’s life though she knows this work can take a toll – including the notorious interview with ABC radio host Jon Faine in which she was asked several offensive questions. Carly was praised for her handling of the event as she used it as an opportunity to highlight the kind of micro-aggressions she (and other disabled people) regularly come up against. But her activism is not just aimed at the media.

CF: But it is a lot of work. Like it’s, it’s – and it’s not easy. It’s not easy to be sometimes disliked. And to put people offside.

I think that often people that work in the disability spaces have good intentions, but are often the most ableist people. I mean, I heard yesterday that a disability organisation hasn’t got any people from that disability group working for them. And I’m like well, haven’t you ever met them? Like, don’t you know where to find them? What, what’s going on here?

I do hope that people that work in the disability space read this and say, “Hey, I’m probably taking up too much space. Let’s give some space to disabled people in leadership positions and people making decisions,” yeah.

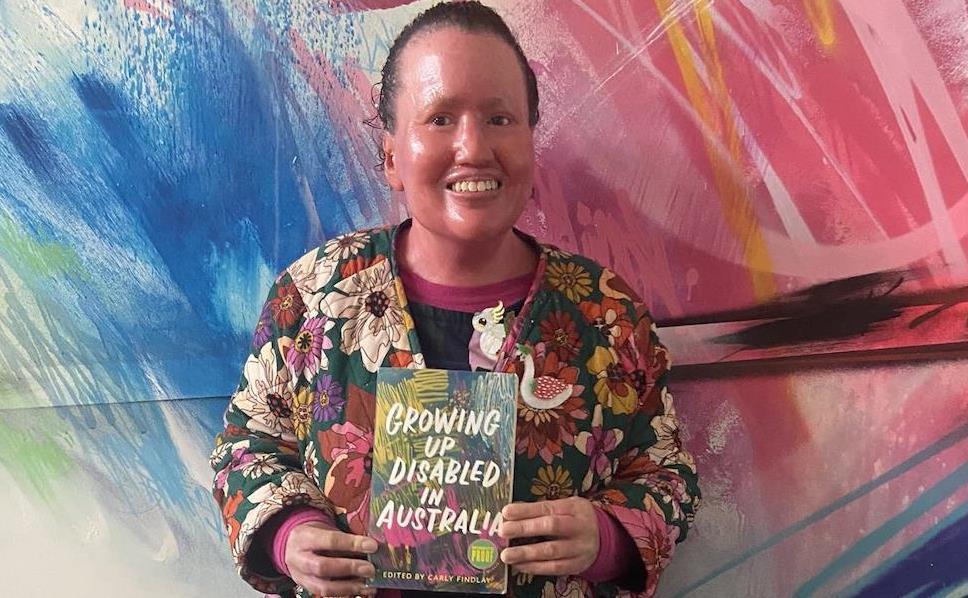

GD: There are many different experiences of disability and Carly aims to show more of them in her work. Her latest book is Growing Up Disabled in Australia – a collection of writings edited by Carly which centres and celebrates the voices and experiences from a wide spectrum of disabled people.

CF: This book is an anthology and there isn’t one like it in Australia, there’s a lot out there overseas, there was a recent one called Disability Visibility edited by Alice Wong, in the US, and there was also Beauty is a Verb and some other anthologies but this one is the first of its kind in Australia. It’s really important that, you know, it is own-voices led and disability led and the idea of “nothing about us without us” is it’s really important. And there are 46 contributors who are all disabled telling their, their stories.

[Classical music plays]

I feel like we see in the media mostly white men in wheelchairs or white women in wheelchairs. And it was very important to me to include a diverse range of stories because I didn’t see a diverse range of disability when I grew up. I saw people who were Paralympians or people on A Current Affair, you know, quote unquote ‘rorting the system’. And we need to see better than that. We need better representation. And that’s not discounting the absolute skill and talent of Paralympians. But I feel that we really need to see that disability comes in lots of ways and lots of experiences, and it doesn’t just look a certain way. And that, yes, someone with a skin condition could consider themselves as disabled; someone who is neuro-diverse might not yet be ready to call themselves disabled yet, but ready to go in a book like this.

People who are chronically ill often get left out of the disability umbrella. And it was also really important to include elders in the book, because there’s people that were born in the 40s, 50s, 60s, who are still alive. And I think it’s showing the power of support and the way things have changed in history.

[Music plays]

GD: Given that media coverage of disability often excludes the voices of disabled people, Carly says a book like this is all the more important – not only in terms of representation but in countering some of the harmful narratives around disability that poor reporting exaggerates.

CF: I always look at the rate of media reporting on Ichthyosis, the skin condition I have, and it’s terribly reported on, really sensationalised, particularly when parents talk about their children as burdens or as scary. And, of course, when a parent says that they love their child, but they also say to a journalist, “well, having a child with a disability is worse than having a child with cancer,” of course, the media is going to pick up on the negative connotation and that’s gonna get sensationalised. So yeah, it is really important that our voices are centered because so often they’re not.

GD: The release of Growing Up Disabled in Australia has been accompanied by a carefully crafted set of media guidelines, which Carly developed in order to ensure appropriate coverage of the book and its 46 contributors.

CF: People are scared of … doing the wrong thing and saying the wrong thing around disability, non-disabled people, even disabled people, I guess, as well.

So I really wanted to prepare journalists to report on this fairly and not to see us as objects of pity or inspiration. I wanted them to use the correct language and not ask inappropriate questions. Because I mean, I’ve had some really awful experiences in the media and I didn’t want the contributors to have that either.

So what we’ve done is…done the media guidelines for media and reviewers. And we’ve also done a much bigger suite of guidelines for the contributors about how to talk about the book, how to promote it on social media, what to do if you get questions you don’t want, what to do if you get a bad review, how to talk to your friends and family and say, “Hey, I don’t want to talk about my story more this is this is all you need to know in the book”. So we’re really – I’m really proud of that…’

[Music plays]

[Adverstisement]

Sabine Brix: 1 in 5 people live with a disability. That’s a huge market for any business. So get your team disability confident, make your online activity accessible and watch your business thrive! Accessible Arts is Australia’s leading arts and disability training provider with great online workshops. Find out more at aarts.net.au.

[Music plays]

GD: Central to Growing Up Disabled in Australia is the social model of disability.

CF:Yes, so the social model of disability means that the society constructs barriers that are disabling. So for example, a physical barrier might be that there is no lift to access the building if you’re a wheelchair user, or there is no Auslan interpreter if you’re a deaf person, which essentially disables you from participating. And then there’s attitudinal barriers, like low expectations of disabled people, or perhaps inspiration porn, which is the term Stella Young coined, about non-disabled people being inspired by disabled people doing everyday things.

And then also systemic barriers, like, you know, the low rate of the disability support pension, the difficulty maybe to get on the NDIS for many people, because that is based on the medical model of disability where they see a body as the fault and something to be fixed. So the social model of disability also sees that the body, you know, is sometimes limiting, but it’s mostly the barriers that can be eliminated.

GD: Those barriers exist everywhere and it is not just about WHO arts organisations currently perceive as their participants.

CF: You know, sometimes when I talk to venues, arts venues or shops or cafes, they’ll say, “Oh, yeah, we we have a step. It’s no issue. Not many wheelchairs come here anyway.” But you know, I wonder why? Because they can’t come.

[Music starts]

GD: Carly works part time at Melbourne Fringe as the organisation’s Access and Inclusion Coordinator. It’s a role in which she’s focused on making the Festival and other Melbourne Fringe events accessible and inclusive for participants and audiences who identify as disabled.

[Music fades]

CF: Yes, so – I mean, there’s so much – I think that it would be great for independent arts organisations to get funding from the government, a whole lot, all organisations really, or get, get some funding so that artists can make their work accessible, because making work accessible is expensive. And so that is limiting to start with, you know, on a small budget for artists. So I would love to see more of that. I would love to see quotas, diversity quotas in organisations – that an organisation needs to reflect the community. So, disability makes up 17.2% of the community in Australia. Are we seeing that in arts organisations? Probably not.

And also just more art commissioned and it doesn’t have to be about disability, just incidental stuff. Yeah. And more accessible venues, you know, like um, being able to be, you know, make some adjustments to heritage-listed buildings would be a start. I mean, I know Stella said that her right to access trumps a right for a building to be heritage listed, [laughs] you know, and, and that’s really important that we see more accessible buildings.

Yeah, and I guess I would just like to see more representation in the arts about disability and accessibility, you know, and the access isn’t an afterthought. I think so often people are saying, “Oh, well, I can’t do everything. Access is an afterthought.” You know? So plan for it from the start, budget for it from the start.

[Music begins]

GD: Now that Growing Up Disabled in Australia has been released, Carly hopes it will bring non-disabled people to confront their own ableism.

CF: If you think “Oh, wow, I couldn’t do what Carly does”. Or, um, you know, “it must be so hard to get around the world looking like that,” you know, that that’s a really ableist thing to think. But I know that you’re thinking in good terms, and you’re thinking someone’s doing a great job, but also you’re pitying that person. So, yeah, I hope that people just take a minute to think about how you know, life is difficult, but also life is good. Like, I really want to see that, to show that disability isn’t something to be pitied or tragic. It’s not always um, you know, sad, and not always discriminatory.’

GD: Many of the stories in Growing Up Disabled in Australia do just that – showing the good and the bad to go beyond those stereotypes and assumptions. The book was delayed due to COVID-19 but it’s out now, published by Black Inc.

[Theme Music]

[Credits]

GD: Thanks for listening to The ArtsHubbub. We’d love to hear your stories of disability and the arts, and how you might have made your practice or organisation more accessible. You can contact us at [email protected] And you can find a full transcript of this podcast on our website.

Our guest this month was Carly Findlay.

The ArtsHubbub is produced by Jon Tjhia, Sabine Brix, Richard Watts and George Dunford. We’d like to thank Michelle Macklem for being our founding producer during the very first year of the ArtsHubbub. Thanks Michelle we couldn’t have done it without you.

Our theme music is ‘Chasing Waterfalls’ by Tim Shiel.

This podcast was produced on the lands of the Kulin Nation. We pay our respects to Kulin Elders, past, present and Emerging. Sovereignty has never been ceded.

Listen to our previous episode of the ArtsHubbub.