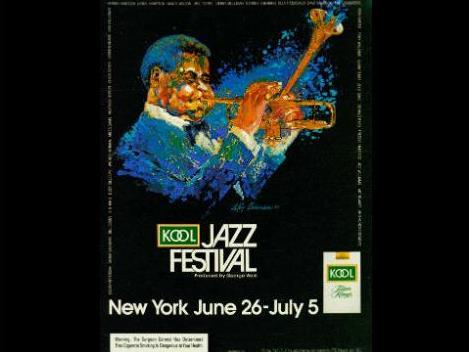

Tobacco sponsorship: Kool Jazz Festival, New York, 1981 Image: Stanford Research

This could become a new battleground for many arts organisations and artists resisting the imposition of a power partnership between the state and business.

In the aftermath of the Arts Minister Senator George Brandis’ interventionist response to artists challenging the ethics of the Sydney Biennale’s arts sponsorship by Transfield, artists and arts organisations are asking themselves and one another this question – in trying to get money for cultural activities, who should decide if there is an ethical boundary where we should draw the line?

Brandis has directed the Australia Council to develop a policy which would make government arts funding conditional on artists and arts organisations not ‘unreasonably’ refusing private sector support. If this goes ahead, a lot will hang on how reasonableness is interpreted and by whom.

After the initial shock and anger, artist activists are mobilizing. Live art group ‘hydra poesis’ alongside ‘pvi collective’, the Perth based tactical media art group recently held a public forum for artists, and is drawing together a group of practitioners from all disciplines and organisations under the umbrella name of ‘The Artistic Resistance Network’ to develop some ethical funding guidelines or a values statement to be adopted by artists and organisations. The National Association for the Visual Arts has pledged its support and other peak bodies may follow suite. pvi describes itself as “an arts group who produce interdisciplinary artworks that are intent on the creative disruption of everyday life”. It has a reputable history of arts activism and has delighted participants around Australia and overseas with witty, playful but serious political interactions eg ‘resist’ which is a live tug-of-war event aimed at testing the notion of conflict and the potential of people power to enact change. Who better to initiate the task of creating the ethical guidelines for artists and organisations in relation to arts sponsorship?

There is a precedent in the guide document produced by ‘Platform’, a London based art, activism, education and research organisation: ‘Take the Money and Run? Some positions on ethics, business sponsorship and making art’. Platform is currently running a high-profile campaign to delegitimise oil companies as acceptable funders of arts and culture. To that end it is challenging the Tate Galleries to divest themselves of sponsorship by BP.

‘Sources of financial support reflect our values, revealing both our ethics and philosophy, and our struggles and contradictions, for it is not a simple road to tread.’ [1] Whether it’s the state, people with large disposable incomes, businesses, institutions or the ‘crowd’, influence is always exerted by those financing the arts. The Sydney Biennale artists’ boycott has highlighted the need for us in this country to think more carefully about the conditions placed on support offered by both the private sector and the state. How might these sources of support impact on the integrity of the art that is made or shown, and what censorship or self censorship is imposed? Could it cause more trouble than it’s worth?While the business activities of corporate sponsors may more obviously present potential recipients with moral dilemmas, no money is completely free from exerting an influence on the artist or art. The funds devolved to the Australia Council come from Australian taxpayers and could be said to be policy neutral. However, politics and the arts are never far apart. Brandis was right when he indicated that the ethics of government funding are coloured by the political environment (in this case he was referring to the asylum seeker detention centre policies). The arm’s length funding principle is an attempt to create a distance between the policies of governments of the time and decisions about arts grants, however, there is nevertheless some flow on effect. For example in Labor’s recent national cultural policy, the instrumental aspect of the arts across all areas of government was a policy focus, whereas Brandis has pledged support for ‘art for art’s sake’.

For many countries, the global financial crisis has been used as an opportunity by conservative governments to make drastic cuts in arts support.

In Australia, both sides of politics have increased pressure to manoeuvre the arts into the orbit of the business sector through gradual cuts to funding and in setting up policies and mechanisms to foster these relationships, in particular Creative Partnerships Australia, (previously the Australia Business Arts Foundation).

The push towards business sponsorship is equally instrumentalising of the arts in their being used to legitimise the reputation of the company.

“The first person you go to [for sponsorship] is someone with an image problem” – Christopher Frayling, former Chairman of Arts Council England.

Twenty years ago it was regarded as perfectly fine for public institutions to gain support from tobacco companies. Now with widespread community acceptance of smoking being a health hazard, it is socially unacceptable for tobacco to play this public role.

Some research would be another valuable next move to examine how much the arts sector in Australia has been directed by public and private sector policies and values through their funding support programs, and to what extent they may have compromised the integrity of the art and artists’ intentions.[2]

[1] ‘Take the Money and Run? Some positions on ethics, business sponsorship and making art’[2] A useful reference document from the UK is ‘Art for All’ which tracks how various Arts Council policy changes have impacted on the arts, artists and audiences over the years. A similar study is needed in this country.