It would seem that a lot of confusion rests in the label itself, the Creative Economy. This was best illustrated during the early days of COVID-19, when early headline data was used to speak about the impact of pandemic lockdowns on the arts sector, by quoting numbers that spoke for the whole creative economy.

Distinguished Professor Stuart Cunningham, QUT Creative Industries Faculty, said ‘The creative arts is a small part – 0.3% of the total workforce of the creative economy.’

The latest report, Australia’s cultural and creative economy: A 21st century guide, from independent arts and culture think tank, A New Approach (ANA) highlights the total estimated value of our cultural and creative activity at $111.7 billion (6.4% of GDP) while employing more than 800,000 people (8.1% of the total workforce).

Cunningham further clarified that, ‘more people work in creative economies than agriculture and mining combined … It is much larger than the creative arts and media sectors … as it includes all creative workers in the general economy as a total.’

‘This incident urged the urgent need for clarity, and for interests to come together, to find a new level of understanding of the creative economy and exploit it strategically,’ added Cunningham.

Online symposium by Australian Academy of Humanities. Top Left to Bottom Right: Professor Jennifer Milam, Professor Chris Gibson, Distinguished Professor Stuart Cunningham, Dr Hye-Kyung Lee, Professor Gigi Foster and Dr Stuart McBratney.

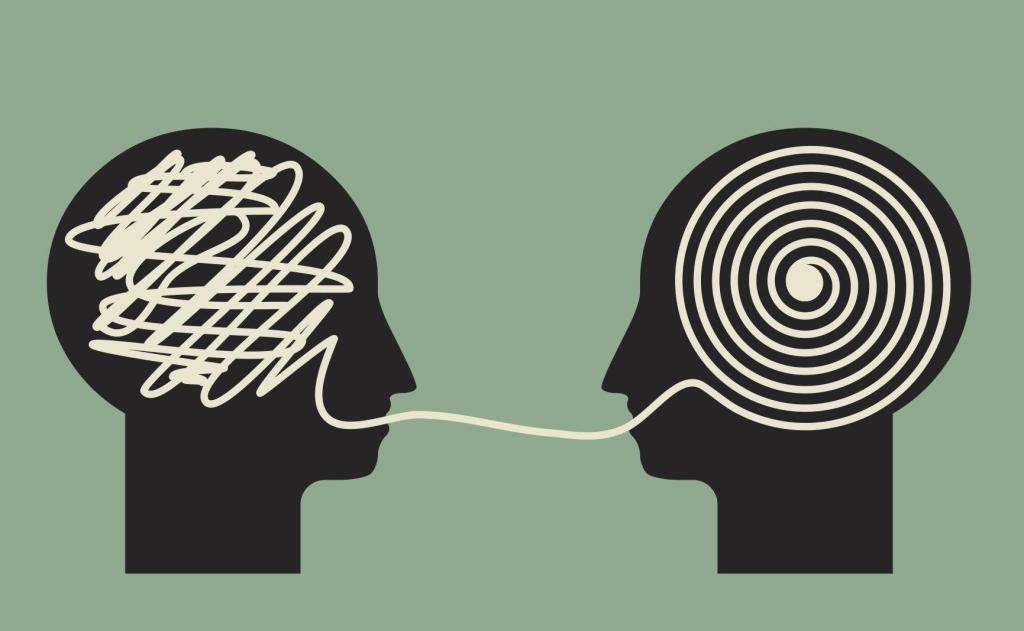

THE NEED FOR NEW LANGUAGE

The discussion Culturing the Creative Economy was part of a five-day online symposium by The Australian Academy of the Humanities.

Cunningham says that there has been, ‘a historical stand-off by the arts and those trying to establish the creative economy, [perceived] as a strange new comer.’

He believes that a lot of that stems from a lack of understanding of what the creative economy is.

ANA’s Australia’s cultural and creative economy aims to demystify Australia’s cultural and creative economy and help drive well-informed public policy that will maximise effective investment and return for our nation.

The report identified design – including architectural services, fashion, graphic design, computer systems design and advertising – as the largest and fastest growing of the cultural and creative industries.

Cunningham said that we have ‘such an underdeveloped understanding because we haven’t learnt to speak in a united voice; that has been a key factor in recognising the creative economies in the UK, for example.’

‘We can’t expect government and philanthropy to be more responsive to us, until we get it right on that united voice,’ he added.

Cunningham believes a united voice will bring the arts to speak of the social, health and cultural value of the arts, as well as jobs growth and jobs of the future, as does the commercial sector. ‘If we bring it together it would be a very powerful lobbying force.’

This is the mixed model that Creative Economies have adopted, aka GDP and jobs thinking sutured to creativity and innovation.

However, the panel was divided on this. Some said we needed to move from old GDP accounting models and establish new models that were better tailored for the arts along social and health lines. Others said it was time to seriously consider a Universal Basic Income (UBI) for artists, along the lines of JobSeeker-style baseline and to use this momentum for policy change.

While other panelists said the solution lay in innovative allyship, better tapping into creative tourism, success of working from home, and more cross-sector thinking with the broader Creative Industries.

THE ALTURISTIC VIEW

Dr Hye-Kyung Lee, a Kings College London Reader in Cultural Policy in the UK, said that we need to ‘find new justification for public support by “re-audiencing” connections with art and culture.’

Lee said this is not a new pandemic problem, and a need for policy shift was on the table well before recent pressures.

‘But with the pandemic we were witness to people losing jobs, contracts and commissions; many were not covered by government schemes. For example, 1.57 billion pounds [of COVID relief] in the UK goes to arts venues and organisations and not individuals. I believe supporting creative people is best way to sustain the Creative Economy. And we need to find ways to keep them in the sector.’

Lee is in the camp of thinking that the culture sector needs to find a new language to talk about the benefits they provide.

‘This new language needs to communicate this long-term nature, where funding today and who gets benefit tomorrow from that. This process can take many years. So direct return on investment is not a good idea.

‘The government needs to function as a patron and invest in long term perspective. This may apply to private funding as well,’ Lee added, saying that there are fantastic examples on long range corporate funding of the arts in Japan.

‘This is a really important moment to consider cultural policy and find a new language to articulate the benefit of culture and the arts,’ she concluded.

THE ECONOMIST’S POSITION

In an unlikely pairing, Lee’s view sat consistent with that of Professor Gigi Foster, Director of Education, School of Economics, UNSW Business.

Speaking as an economist, she said her profession, ‘thinks of economic activity, of any sort, as one to maximise human welfare – all our advice for activity is to get the most human value out of those activities.’

Foster said that, ‘the economist is never in any one corner, as they take a holistic view,’ adding that she believes ‘most jobs have a creative component to them’.

She was less convinced that tethering the value of the arts to jobs and GDP was the path to follow. ‘I think that is very limiting … and brings a disservice to the arts’ impacts on human welfare.’

Foster explained the simple economics of funding: ‘If we are going to fund something – either a private investment or a government decision – then the additional value you are giving back must be as great as the marginal cost you are contributing. That is a justification for government intervention into what economists think of as market failure, and that is usually when it is considered a public good.’

She said arts and culture largely fall in this area of public good, and that this is where we need to focus our language.

‘The arts help us maintain values like empathy, trust, peace, and to understand that we are all in this together in the world; it also provides us an opportunity to reflect, and that is directly positive human welfare.’

Foster said it is that public good aspect that we need to focus on to harness funding, and to move away ‘from measuring just GDP per capita to measuring human wellbeing… so that government can more easily see that dollar relationship to the outcome, and their social responsibilities.’

It was an argument that Professor Chris Gibson, University of Wollongong, presented in a different way.

‘The pandemic has showed us what kinds of jobs are deemed in the National interest and worth buttressing,’ said Gibson. He made the quick bullet points to provoke the panel’s thinking, and to illustrate what he described as an ‘uneven’ perception of value and lack of language penetration:

- promoted is a gas-led recovery, but they will become stranded assets in the next decades;

- look at who was recruited to recovery committee; the arts simply not represented at all;

- the arts were largely excluded from JobSeeker;

- the NFL grand final was permitted to go ahead with 50,000 fans, despite the pinch points entry, but Sculpture by the Seas was considered unsafe and therefore cancelled.

He suggested rather than framing the arts worth along obtuse or intangible values, to turn to allyship as an alternative option, which sat somewhere between the polarised views.

THE ALLY

Cunningham said that, ‘current research into regional creative hot spots has conveyed that communities are proud of these facilities. So buddy up to your complementers or ally industries. If they don’t know about you, then help them to know.’

He said we need to work harder at the arts tourism pairing. The number of visitor participation in cultural activities increased 70% in 10 years to 2019. ‘Regional hotspots are important to understanding that continuum,’ Cunningham said.

Gibson extended this idea to the prosaic structures of our communities – libraries, girl guide halls, and the like. ‘In a pandemic, and post-pandemic environment, what of those prosaic structure will survive, and how adaptable will they be to that more local working at home environment? How easy can these buildings be rejigged to adapt to creative activities?’

He said that we were witness to a migration of makers from shared creatives spaces back to home studios during the pandemic.

‘It showed the vulnerability of these makers [in creative industries] but also showed their ability to respond quickly and be flexible – there are some interesting questions around that when considering the creative economy at large and where the arts fits in.’

Gibson continued: ‘I agree with Stuart (Cunningham) that tapping tourism is key … The small-scale manufacturing craft sector – or makers – work more with renewed interest in local products or at local events. There is a really granular geography element to this.’

IS A UNIVERSAL BASIC INCOME THE RIGHT CASE TO PUSH?

Panel chair, Professor Jennifer Milam, University of Newcastle Pro Vice Chancellor, raised a UBI, which had been a regular discussion point across the five-day symposium.

‘In the first of the symposiums session, Wesley Enoch proposed a universal basic income and suggested that artists wouldn’t be as precarious in their work. It also taps into Chris [Gibson’s] idea of geography,’ said Milam.

Gibson saw the greatest benefit of a UBI as one of time.

‘Time itself has become scarce, not just [financial] resources. In the ‘90s we had a lot more time. Bands and filmmakers had time to hang out and experiment, to learn how to use a bit of kit, but now in a speeded-up society – and the cost of property and real estate being so high – people are working longer hours and the pressure on productive is much greater.’

‘The political debate is not on creating creative economies, but more traction on capacity to volunteer, for example, on wellbeing,’ continued Gibson adding this as a counter position to the GDP value proposition.

Cunningham expressed concern to let the future of the sector rest in its definition, ‘for the better good.’

‘By going for the moonshot [of a UBI], we do not focus on incremental change,’ said Cunningham. ‘I am a reformist rather than a revolutionary. Modern monetary theory and a UBI share a kind of seachange. But it is a much wider debate.’

‘The ability to afford would require a massive change in financing, and the massive debts that government is racking up with COVID, would suggest these moon shots mean [little] to the actual decision makers – the politicians, who make budget decisions, said Cunningham.

He steered the panel back to where we started – how we define creative economies and better riff off that idea.

‘This is supposed to be about the Creative Economy. I don’t think the idea to move beyond these tried and tested methods – like GDP – are the bases on which advice should move through to policy makers.

‘The fact is, in this country we have only begun the merest beginnings of a public debate about the size of the Creative Economy – let’s not short sell it! Let’s deal with the here and now as well as the moonshots,’ concluded Cunningham.

“DON’T THROW THE BABY OUT WITH THE BATH WATER”

‘So how does this economic research translate to politicians: it is jobs growth that is a really important thing for them. We need to integrate the non-economic claims of value that people in this panel have presented for arts and culture, along with the bottom-line jobs creation that the rest of the creative economy can deliver – to bring that together into a coherent package,’ concluded Cunningham. ‘That is the key to us going forward.’

‘We don’t have to say let’s get beyond economics; let’s get a package that works across both ends of the spectrum of the arts and creative economy, he concluded.

His closing advice was to go knock on the get and get data to politicians at an electorate level. ‘What is going on in your electorate that is creative activity? How many in your electorate are a YouTube creators? How many are using games? This is the way political language works at an absolute grass-roots level. The data will be a complete surprise to them.’

The panel discussion Culturing the Creative Economy was presented 20 November 2020 as part of The Australian Academy of the Humanities Symposium.