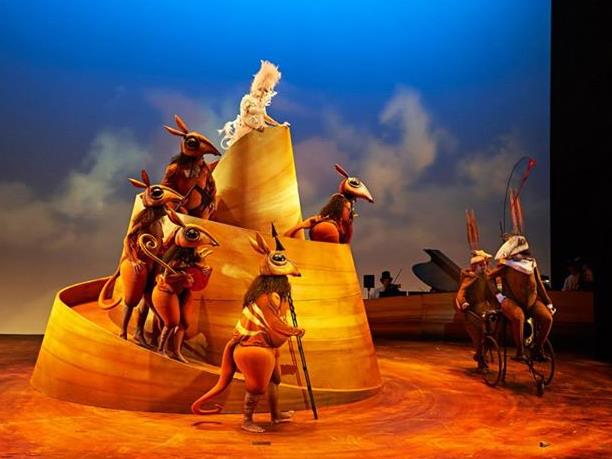

New opera: The Rabbits, Photo: Jon Green, Image via Opera Australia

There was a time when there was only ever new music. In fact, it was an incredibly extensive period of time lasting from when mankind first became of aware of music and later began to notate and consciously compose music.

This lasted, more or less, until the advent of the recording. Recorded sound put a brand new perspective on music and listeners became used to hearing the same piece of music again and again.

This is not an inherently bad thing but it does place the idea of an ever-increasing repertoire of new music in a difficult circumstance. The advent of film, video, DVD and the like has also had an impact on new music in two ways. More composers than ever have had opportunities to compose music for film, DVD, video games and so on, and this music has in turn had a profound effect on compositional styles.

The breadth and depth has changed dramatically and the audience base has grown exponentially. Technology has, in part, had an impact on the way in which we listen to and understand music and has also had an impact on composers of orchestral music.

I became aware of the existence of orchestral music in the 1950s when I started going to concerts at the Sydney Town Hall, performed by the Sydney Symphony Orchestra. To my recollection, there was almost no contemporary music of any description programmed.

The advent of the Sydney Symphony prom concerts in the 1960s saw an increase in the amount of new music being played. These concerts sold out and the essentially youthful audiences showed their appreciation for the new music in all sorts of ways. The inclusion of contemporary music in symphony orchestra programming, at least as far as the Sydney Symphony Orchestra was concerned, had changed forever and for the better.

Gradually, more and more Australian works were being included in orchestral programming, albeit at a relatively slow rate and equally gradually, audiences became aware of the existence of Australian composers. Music of Carl Vine, Peter Sculthorpe and Ross Edwards was included on the orchestra’s international tours, presenting Australian composers to the world.

In my time as a conductor working with the network orchestras, some of the country’s youth orchestras and The Australian Youth Orchestra, I have conducted the music of well over forty Australian composers including works composed by well-established composers and emerging composers.Many of these works have been world premieres, commissioned by the Sydney Symphony Orchestra for its Meet The Music series.

As Artistic Director of the Sydney Symphony Education Program from 1994 until 2013, I made certain that there was an abundance of new music in the schools concerts, including Australian, European and some American music. We also featured an Australian composer of the year, which included a work of this composer for every grade level so that schools could build their resources of Australian music.

As a result, thousands of school children have had live orchestral experiences of new music, which they received much more readily and with much more acceptance than their adult counterparts tend to do, demonstrating that if you approach them at the right age, before biases and musical tastes are created, children will readily accept a whole range of music and approach it fearlessly.

I have programmed Schoenberg, Webern and contemporary Australian music to children who accepted it and talked about it freely and interestingly. It was not a big deal, to use the vernacular. They heard it all as music.

New music can be promoted and audiences will come. It can be done. However, it seems that the bigger the organization the more difficult it is to commission and perform new work. Nonetheless, it is important to remember that things have changed spectacularly in this country in my lifetime and continue to change.

Complacency, self-satisfaction and a lack of concern for the common good are the enemies of creativity. Advocating aggressively by constantly stressing the negative is also counter-productive. We need advocacy which is good, which is thoughtful and productive, presented by musicians who understand the importance of new music to a society.

In order to enhance the importance of music in and to a society, it is essential that the music education, which takes place, or should take place, in the early years of a child’s life, be as comprehensive and as vital as possible.

We all need to work together to promote music education locally and at the national level.

We need to agree on the following things:

- that every child in Australia should have access to a thoroughly qualified and properly trained music teacher

- that we teach music because it is good and unique and no other justification is required

- that we teach music so that children can make their own music – that is new music

- that we teach music based on singing, and that all conceptual information related to the teaching of music comes from singing

- that we teach music so that children can learn to develop an appreciation and understanding of the music of others.

In the schools is where the music of the future will be found. This is where the new creative minds will be developed, where boundaries will be explored, where technology will be better understood by the new generations than any preceding generation and where we hope brave new worlds of imagination, new thoughts and new inventions will emerge.

I am trying to persuade as many music organizations in the country to join the Australian Society of Music Education, Australia’s peak body, founded purely for the purposes of advocating music education, so that we can form a powerful lobby at State and Federal Government levels. Were all educational organizations to be under one umbrella organization, ASME, it would represent a powerful constituency to which governments might potentially listen.

A program to assist all of this in the form of the National Music Teachers Mentoring program, under the auspices of the Australian Youth orchestra, is now well and truly underway; a program with State and Federal government support. This program harnesses resources which already exist, in the form of specialist teachers working as mentors alongside other teachers.

New South Wales is leading the way with this program and has committed to maintain the program for 2016. Western Australia and Victoria are currently engaged with the program and South Australia and the Northern territory will come on board in 2016.

Along with this program, I am currently in conversation with a tertiary institution in this country to establish the National Institute of Music Teaching. This would be a specialist institution involving practice and research into the teaching of music and would encompass all aspects of music including music of the popular cultures. It would also have a school attached as a demonstration school encompassing classes from pre-school to upper primary, and would be in essence, a teacher training facility.

Together we can change the musical landscape of Australia. Together, we can, if we invest wholeheartedly in music education, raise an ever-increasing awareness of new music and bring with us whole new generations of composers, performers and listeners who will have a strong appreciation and refined understanding of music, especially new music.

This article is an edited extract from the Peggy Glanville-Hicks Address 2015. The full transcript is available at the New Music Network.