In 2016, Ngoc Vu was a newcomer to the games industry. After graduating university and taking a brief contract with Melbourne studio Samurai Punk, she was part of the founding team Melbourne-based studio Route 59, alongside creative director Kevin Chen, artist Joe Liu, and writer Justin Kuiper with the support of Film Victoria through their Assigned Production Investment fund. The team were developing Necrobarista, a dark, sensitive, aesthetically sumptuous visual novel about a coffee shop that exists between the worlds of the living or the dead, where the spirits can spend their last 24 hours on the mortal plane.

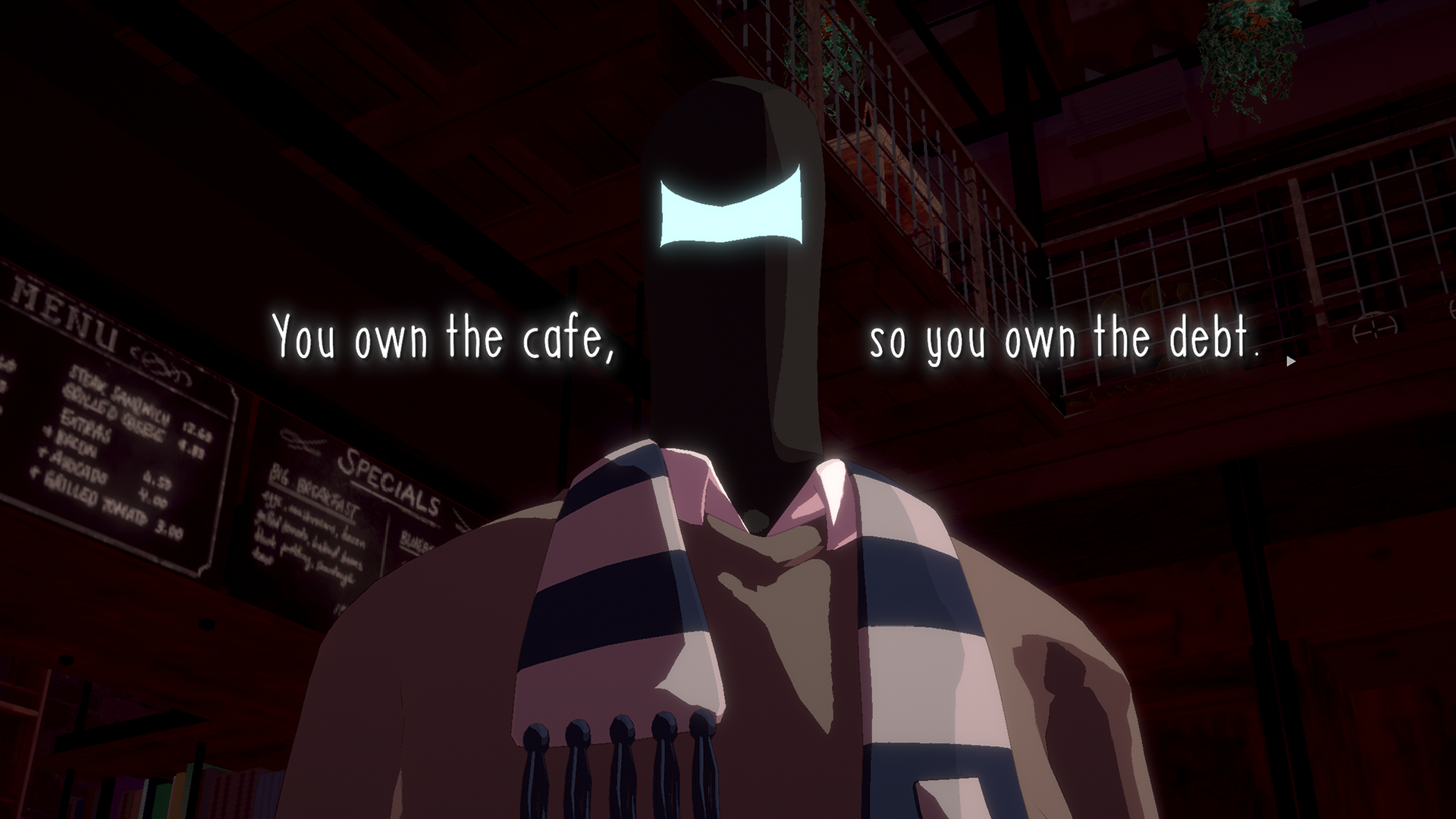

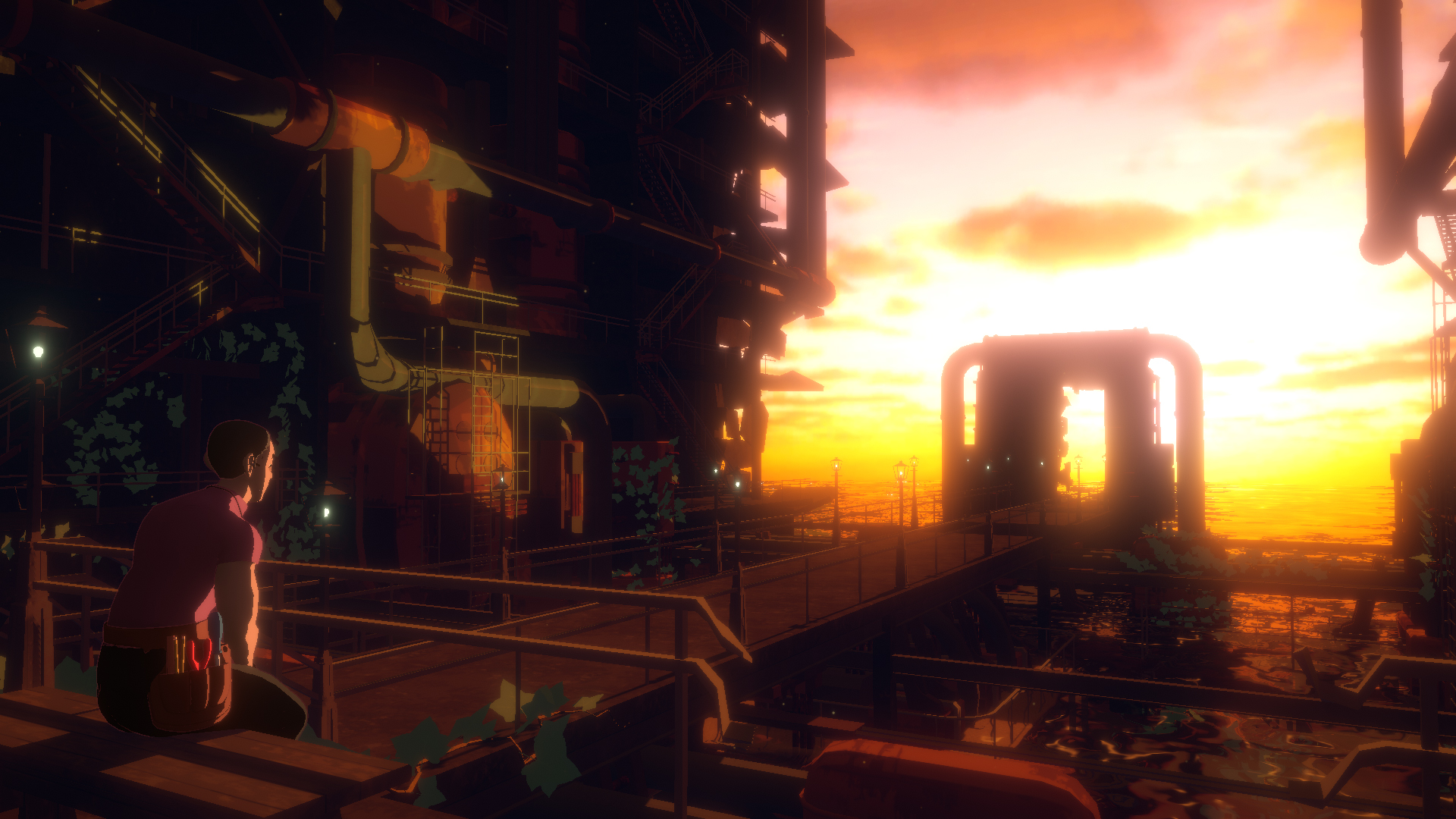

A skilled 2D and 3D artist with a distinctive flair for character art, Vu took on the role of Lead artist, and over the game’s six year development cycle, she directed a small team of artists that brought acclaim to the project: with every trailer, the hype around the gothic, distinctly Melburnian world of the game grew. And on release, it was critically lauded. Necrobarista currently boasts a Very Positive aggregate rating on Steam, and even drew the eye of Nier director, Yoko Taro.

「ネクロバリスタ」をプレイ開始。内容は説明しづらいので、リンク参照。冒頭だけプレイしたけど、不思議な感じのするノベルゲー。あ、あと、日本語ローカライズが最初からされてるの最高……

>「Necrobarista(ネクロバリスタ)」のPC版が本日発売。 https://t.co/v95MQHRj0m pic.twitter.com/pYTLhACHSm — yokotaro (@yokotaro) August 10, 2020

Among many award nominations, the game ultimately won AGDA and Freeplay awards for Best Art based on Vu’s work, and the work of a small team she led. But now, she’s alleging that Chen and Route 59 owe her over $10,000 in superannuation. Her claim is supported by Necrobarista cinematographer Brent Arnold, who also alleges late and missing payments during production, as well as late payments on his revenue share.

Vu said she ‘would not trust [Creative Director & CEO] Kevin Chen with any financial agreement like royalty share with [her] life,’ in a public statement on Twitter.

I would not trust Kevin Chen with any financial agreement like royalty share with my life. Be warned. I’m tired of his inaction of not paying me my dues and I cannot advocate his activities within game development until my super owed is paid in full

— ngoctmvu 🇵🇸 (@ngoctmvu) June 18, 2021

Vu had all but given up on chasing down the money she was owed; the process had been laboured, and emotionally fraught: ‘I was rather traumatised [after leaving Route 59], and didn’t really want to contact them again.’

The fact that the studio failed to respond in any way compounded this trauma. While Chen had acknowledged the amount owing in a meeting in October 2020, and Vu followed up via email as recently as January of this year after switching super funds, she still hadn’t heard from the studio.

That is, until she went public: since then, she’s received correspondence from the studio’s accountant, who confirmed on 21 June that she had been owed a lump sum of $10,184. The email also confirmed that since December 2020, $1947 of this has been repaid, leaving $8,296 still owing.

It’s the first movement Vu has seen since she left Route 59 upon Necrobarista’s release in July 2020.

Yeah I could see how sketchy it was in real time and developed some seriously negative hypervigilance over the years. For me it was probably sunk cost fallacy, I wanted to put my all into the game and that’s an easily exploited trait. I’m still really proud of the work I did.

— Brent Ryan Arnold (@BrentRyanArnold) June 18, 2021

WHAT WENT SO WRONG?

Vu’s primary concern was the lump sum owed, and the lengths she had to undertake to recuperate it. But as we talk it becomes clear that financial issues wove their way throughout Necrobarista’s development, not just at the end; she struggled to get remittance advice on submission of invoices, and, despite her long tenure with the company, remained a contractor the entire time.

Also a reminder that Necro came out in July 2020 🙂 almost a year waiting for something that has never come

— ngoctmvu 🇵🇸 (@ngoctmvu) June 18, 2021

Another contractor described late and inconsistent payments throughout development, and unclear or misleading information around compensation for labour. Like Vu, they were a recent university graduate, and lacked the experience to know whether or not their remuneration was fair:

‘The ad I responded to was a 6 month contract of $20-$25k based on experience. In the interview I was told it would be 10 milestones of $1500 each. This didn’t add up but I was fresh out of uni and excited so I went for it. Each milestone took me a bit over a month of full time work to complete. This was very difficult financially but it was exciting to work on the project. This also exceeded 6 months quite significantly, and eventually there wasn’t money to pay anyone.

‘We were asked individually if we would keep working for rev share. I don’t know what others discussed, but I was told that a conservative estimate of my percentage would be worth $10k. This did not hold true […]

‘Eventually the company had some money again and we were able to get paid more, and consistently, I was no longer being paid by milestone and instead it was closer to a salary.’

When the company stabilised financially, another issue arose: the team was heavily reliant on long-term contractors. Despite expanding responsibilities and time commitment, they were not transitioned to employee status.

PERENNIAL CONTRACTORS

The obligations and benefits of contracting versus employment differ significantly. One of the key differences between a contractor and an employee is the degree of control that the employer is legally allowed to exert over the way that they work. Where an employer may designate the times, location, and method of an employee’s work, a contractor typically has more freedom: according to the Australian Taxation office, unless it is specified in their contract, controlling the times they work, or location of their work, is illegal.

One contractor told Screenhub that, despite a lack of contractual stipulation, they were asked to work hours set by Chen, and after the studio pivoted to working from home during Victoria’s pandemic lockdowns, they were told to work with their webcam on at all times.

Necrobarista. Image: Route 59

After working on the project for two and a half years, they were let go overnight, despite having recently signed a renewed contract. While the studio cited financial constraints, they told Screenhub that they suspected other factors:

‘I had been vocal about an issue I had with the way we [the contractors] were treated as employees around our contracts. We were legally considered contractors, but a lot of expectations placed on us treated us like full time employees.

‘I wanted the distinction to be clear, either continue to have us on as contractors and treat us as such, or swap us to full time… I was just considered expendable, but after being with the studio for over 2 years and putting in an enormous amount of work that felt pretty bad. But this whole line of thought is conjecture and it’s just my feeling, nothing more.’

GETTING INFORMED IN THE GAMES INDUSTRY

Vu described her Necrobarista salary as ‘meagre.’ She noted that, on top of the superannuation she was owed, the studio encouraged her to sign over her share of the game’s revenue in return for a lump sum, citing lower revenue than projected.

Eventually, she chose to accept a lump sum of $40, 000 to divest completely from the company and game – a sum she considered reasonable. In her words, ‘40k to just drop and not have to correspond to them each month seemed good.’

But it’s a decision she had to make with little support or advice: in July 2020, Melbourne’s second lockdown was in full force, it was difficult to connect with legal advice.

For Vu, the immense difficulty of finding appropriate professional support with a specialisation in her industry was one of the most frustrating parts of the process. In fact, she struggled to find a lawyer with any experience on game development contracts, as the only games-specific legal counsel she was familiar with already worked for the studio.

Ultimately, while she thinks the payout was fair, it was a decision with long-term financial consequences that she had to make without the legal and financial advice she would have expected to be able to access in another industry.

This was a disempowering experience that left her constantly second-guessing her own decisions: ‘with my inexperience, I feel bad I didn’t push it further,’ she said.

I asked Vu what her advice to other emerging game developers would be, and her response was searingly practical. Game development is a business, and, while the process is artistic, it’s not enough to master your craft; you have to understand the money, too. ‘See an accountant. Learn about your obligations as a sole trader. Have amounts earned on paper.’

It’s advice that could easily extend to emerging studio leads as well.

THE BUSINESS OF ART MAKING

Videogames are an art form, made by artists. But the labour that a studio undertakes to create a game is distinct from the creative labour of an author writing a book, or painter creating a portrait. A games studio is a small business first and foremost, and lacking the business acumen to run a company – regardless of the intentions of the business owners, and artistic merit of the product – can have dire consequences.

Kevin Chen was the lead designer of Necrobarista, as well as the creative director of Route 59. Like Vu, he was drawn to game development as a form of artistic expression: Necrobarista, then known as Project Ven, was first prototyped as Chen’s third-year game development project during his game design Bachelor degree at RMIT.

Chen has overseen the financial management of Route 59 since the year after graduating university. His game design degree didn’t cover business management, and aside from some advice from others in the local indie games scene, and a few business coaching workshops hosted by Film Victoria and RMIT, he had no training or support in the area.

He takes full responsibility for Vu’s missing superannuation: ‘I received the statement from my accountant on the 13 April, but failed to act on it until 21 June. Moving forward, I have set calendar reminders so nothing like this occurs again with superannuations or quarterly payments.’

He acknowledged the long-term financial issues raised by his former contractors, citing his own inexperience as a leader as a key factor in the ongoing issues the studio faced: ‘When we started the studio, I heavily undervalued the importance of business/leadership skills, especially the more bureaucratic side of things.’

Necrobarista. Image: Route 59

He described Necrobarista’s development cycles as being undertaken by an ‘informal’ and ‘stretched’ team, where each member was under pressure to perform outside of their job expectations, including Chen himself. In a self-fulfilling cycle, this lack of management frequently led to Chen focussing on immediate and pressing tasks, rather than structural issues in the company: ‘This often led me to de-prioritize business management in lieu of working on the game.’

Combined with the fact that the founding team started out as friends before they were colleagues, Chen describes a dynamic that led to a ‘very casual handling of payments and invoices – everything would still be paid of course, but would often lack a clear structure around the process.’

ART DOESN’T PAY

Regarding salary and revenue share expectations, Chen situated Route 59 within a landscape of struggling indies that simply can’t afford to pay salaries at an industry standard: ‘I know many people are aware that several indie studios fail, but even then I think a lot of people still think of it as a dichotomy of “failure” or “make it big as the 1% indie superstar”‘.

‘In reality, there are a lot of studios that are just surviving. Despite the critical success of Necrobarista and having a cult following, development took years longer to complete than we initially forecast, and sales have been below expectations.’

Chen considers the expectations on new startups to meet the earning standards of an established studio are ‘unrealistic: ‘This in turn leads to a lot of disappointment when it comes to how much we made – we have a flat wage system where everyone working full-time is paid the same amount, including myself, and while I can understand some of the frustration, the fact of the matter is surviving in the industry is quite hard and not very lucrative.’

I spoke to Tim Colwill, an organiser at nascent games union Game Workers Unite Australia. He recognised that new, independent studios are in a drastically different financial situation to established companies. For many, hiring contractor is a way to circumvent minimum wage requirements that are unfeasible on tight budgets: ‘Independent studios which are never going to be able to meet those requirements are going to be better off negotiating a strong profit-sharing arrangement between each other as contractors, ideally including a lump sum payment up front in case something happens and the project does not reach completion.

‘This ensures that everyone is getting as much as they can out of the work, and all profits are going back into workers pockets. It also creates trust between workers and a better workplace.’

But lack of funds doesn’t excuse other poor workplace management. GWU Aus advocates for ‘transparent contractual arrangement[s], and an equal and fair profit share for everyone involved,’ even in the cases that profits are low. While money might be tight, indie studios obligations extend beyond the financial: ‘our goals are for fairness and equality in the workplace. This can be thought of not only in terms of pure wages, but also in terms of power dynamics, representation, and outcome.’

CREATIVe WORK IS WORK

The struggles of indie development studios will be familiar to other arts workers, for whom volunteering, overwork, and underpayment are sadly par for the course. In the case of indie studios, Route 59’s struggles are endemic throughout the games industry, which largely relies on project-based funding, rather than studio funding or investment, and small, often informal teams.

Trauma is so cruel. I’ll be working on a mesh and then I’m paralyzed in my chair for a half hour :/

— ngoctmvu 🇵🇸 (@ngoctmvu) June 28, 2021

In 2019, Dr Brendan Keogh’s research into the cultural field of videogame development in Australia found that independent developers who work like this, on small budgets, making up for a lack of resources with ‘sweat equity,’ are far from the exception to the rule in the game development industry. His research showed that many game developers in Australia make games primarily in their spare time, after hours, or for the promise of revenue share in lieu of a salary.

Keogh’s qualitative research suggested that there were some benefits to an informal mode of working for some game developers; creative expression, the freedom of a fundamentally non-commercial arts practice and IP ownership were among the animating forces behind this body of labour.

But the creative opportunities here create an environment ripe for exploitation: for contractors who are treated as full-time employees, these benefits are hardly felt: without the money, freedom, creativity or sense of ownership that informal game development practices can offer, this model relies on the fetishization of creative labour that pervades the arts. Rather than opening up opportunities for artistic expression that is only possible outside of the framework of a 9-5, it can create an environment where game development labour is wholly undervalued, both financially and creatively.

In the case of Necrobarista, what can be abstracted as a structural issue had real personal consequences. Vu regrets the time she spent on the project, and feels traumatised by her time with Route 59: ‘I can barely open Maya without crying. It’s some miracle I can still work, I think,’ she said.

What can be done?

Increasingly, there are resources out there: Colwill recommends that, while expert legal and financial consultation in game development can be hard to find, GWU are able to offer some assistance: ‘we are absolutely ready to assist any members who want to come to us with advice about their rights as an employee.’

He continued, ‘we have reviewed dozens of contracts from Australian employers big and small, and can give confidential advice which reflects trends and standards in the industry.’

As GWU Aus moves towards becoming a formally recognised union through Professionals Australia, their resources will continue to expand – and given the makeup of the local industry, Colwill has always put freelancers front and centre in the union’s negotiations. In May, he told Screenhub that ‘history shows that freelancers and contractors, too, stand to make massive gains from working together that they never would have if they stood alone.’

Initiatives like tax offsets can also help stabilise studios as they move from one project to the next — South Australia’s 10% videogame rebate would likely be accessible to a team of Route 59’s size. But many business-focussed initiatives, like the proposed national 30% digital games tax offset, which has a $500,000 minimum spending threshold, will inevitably be inaccessible to some of these less established studios.

Necrobarista. Image: Route 59

Ultimately, it is an issue of personal responsibility. Videogames are an art form, made by artists. But the labour that a games studio undertakes to create them is distinct from the creative labour of writing a book, or painting a picture, because a studio is first and foremost a business with an intrinsic power structure that easily be abused. This has a destabilising effect on the industry as a whole, as aspiring game devs get burned early in their careers and move on to new industries.

At the crux of the issue is the fact that business management within a games studio isn’t just about maximising income: strong internal structures, including financial structures also facilitate healthy power dynamics within the team, and respectful, transparent communication. Otherwise, the underpaid, overworked labour of making artistic games will come at a heavy emotional cost of the artists.

Without a major systemic shift, history is doomed to repeat itself: studio leads without the appropriate qualifications will struggle with the multivalent responsibilities of business management, and small, artistic studios populated with relatively inexperienced workers will pay a sweat equity on their underpaid labour, whether they’re wholly convinced it’s worth it or not.