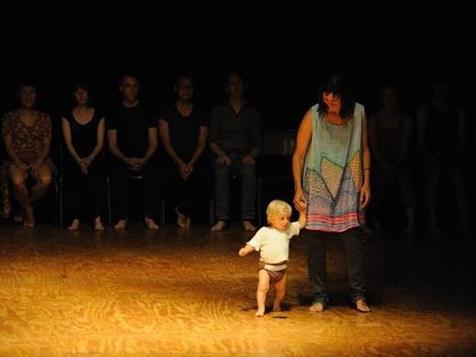

Image: Jane Mitchell

I was recently at a friend’s birthday barbecue, held in a park in the early evening. About 40 people were there, primarily in their late twenties or early thirties, all practicing artists, art teachers, arts industry professionals or students. And I was the only person there with children.

It is not unusual for me to be the only parent in a room: in my mid-twenties, when most of my friends were living in share houses and swiping left on Tinder, I was happily mortgaged to the gills, pregnant and in a long-term relationship. But most people at that barbecue were smack bang in the middle of the average childbearing age in Australia (30 for women, 33 for men) and my children were the only ones covering everything in tomato sauce and running amok.

It wasn’t just a coincidence that these creative people don’t have children – parenting takes time, money and energy, all resources that are equally sucked by a creative career.

Clashing time lines

One of the biggest barriers to parenting for artists is the time it takes to get a career happening. For most people in the arts industry, it takes many years to get to a stable enough place to consider starting a family.

‘Creative careers can be less well paid, more volatile, and take longer to establish,’ said Honor Eastley, founder of Starving Artist, a podcast uncovering how artists make money.

‘A lot of people are told to “try out” their creative career, but that they should have a plan B. And maybe they are still seeing if it will be viable, before they put a kid into that financially unstable situation.’

‘One of the artists I interviewed for Starving Artist – an exhibiting contemporary artist – said that artists don’t start establishing a career until they’re 40. And that is why there are many more men at that level. If you want to have a kid, it won’t work.’

The problem is aggravated for women. ‘I think it was [UK feminist writer] Laurie Penny who said that you have to have it figured out by the time that you’re 28,’ said Eastley.

Often for a woman to have a creative career and children, she must either have kids early and only begin the career once they are a little grown or delay parenthood until her creative career is established enough to support a child, remembering that if she has not got there by 40 the biological reality is that her chances of conceiving are greatly diminished.

Image: Paul Dunn for the Museum of Contemporary Art, Australia.

On the art track

Sally Arnold, a flautist and former business development manager for The Australian Ballet is child-free by choice, a decision she made when she feel in love with music as a child.

‘Growing up in Christchurch in the 50s and 60s was pretty ordinary, and when I discovered I had a talent for music, my life went from black and white to colour. I still remember telling everyone as a child, “I’m not getting married and I’m not having children, I’m going to be married to my flute.’

She still believes it was the right decision, having seen many dancers and musicians struggle with balancing a burgeoning career and a young family. ‘If you are in your twenties and still don’t have permanent employment, especially as a muso or a dancer, that’s when I imagine you would start thinking, “If I have a child, that’s just going to stop everything”.’

A career in the arts is often non-linear and slow growing. ‘ ‘If I’m looking at my peers who are all in that similar age bracket of mid-thirties and all trying to get to that next level, financial stability is still an issue for a lot of us. A lot of us are questioning if we will ever be able to buy a house in our lifetime, can we afford to stay in Sydney and what on earth can you potentially do if you want to start a family?’ said writer and director Kim Ramsay. ‘In Australia I look at some of the filmmakers I admire and it took them between eight to ten years to get their first feature film up – and that’s a long time.’

Many artists work on developing a commercial income to support creative work but that double life leaves little time for parenting. ‘Particularly when you are freelancing and the best way to make money through freelancing is to try to crack into the commercial world or the corporate side of things while you are trying to get your film off the ground. So getting a foot in the door there can sometimes take a while initially,’ said Ramsay.

Many of my own peers are working part-time, casual or freelance jobs in order to make their art, and between piecemeal work, an artistic practice, and shoddy parental leave and childcare access in Australia, planning for a family seems like a far-off goal for many young artists. But many artists are still considering whether or not to have kids. ‘One of the fears that led to me starting Starving Artist was this biological anxiety, the “to parent or not to parent question,”’ said Eastley.

The pram in the hall

Aside from the financial issue, the impact that parenthood has on an artist’s creativity can be concerning for creative types who are used to throwing themselves completely into their art practice. English literary critic and writer Cyril Connolly famously observed, ‘There is no more sombre enemy of good art than the pram in the hall.’

While things have changed since Connolly’s mid-20th Century epithet, women still struggle with the fear that parenting will sap their creativity. When I fell pregnant for the first time, I feared losing a sense of self and motherhood setting me back from all the hard work I had done in my career and my creative output. Was I prepared to compromise?

Some artists have gone so far as to attribute aspects of their success to their decision not to have children. Marina Abramović made headlines last year by telling a German newspaper, ‘In my opinion [having children is] the reason why women aren’t as successful as men in the art world. There are plenty of talented women. Why do men take over the important positions? It’s simple. Love, family, children—a woman doesn’t want to sacrifice all of that.’

And talking to Red magazine about not having children, UK artist Tracy Emin said: ‘There are good artists that have children. Of course there are. They are called men.’ Emin maintained that having children would ‘compromise’ her work. ‘I know some women can. But that’s not the kind of artist I aspire to be,’ she said. ‘I would have been either 100% mother or 100% artist. I’m not flaky and I don’t compromise.’

Balance of power

But is parenthood necessarily a compromise or a sacrifice?

Certainly few artists can muster the support and privilege of some of those who champion the capacity to have it all, like Facebook COO Sherly Sandberg, author of Lean In.

But there are also plenty of well known artists, writers and performers who are mothers: Laurie Simmons, Annie Leibovitz, Toni Morrison and Zadie Smith all had children at the height of their careers. According to Abramović and Emin, would these women have been more successful had they abandoned family life and focused only on their careers?

Or does this thinking hold women back and perpetuate another fantastical myth of the artist as loner, one who suffers for creativity? Many male artists and writers can peddle the illusion of being creative loners while also being partners and parents—Kurt Vonnegut, Damien Hirst, Ai Weiwei, Stephen King and many more are fathers. Why are female artists are expected to forgo children in order to meet the same standard?

American artist Miranda July said in her Wheeler Centre talk in July last year that she had been working as an artist long enough to recognise that the pattern was ‘work as hard as you can on something – as hard as you possibly can, then do that again.’

While having children inevitably produces logistical hurdles and organisational requirements, it also becomes one more life challenge to grapple with, and a choice that ultimately enriches lives and careers, more than hindering them.