British nature photographer David Slater faces court over the authorship of a selfie that a macaque took using his camera.

The now infamous “Monkey Selfie” case contesting the authorship of British nature photographer David Slater, was back in a US court July 2017. Coincidently the same week, artist Richard Prince was also facing legal dramas after a motion to dismiss was denied by a federal judge in New York regarding a copyright suit of an image plucked from Instagram and used by the artist.

What do these two cases have in common, and what can Australian artists learn from them? They come at a timely moment when copyright holders are trying to understand the parameters of new fair use laws, and how images posted via Instagram and social media channels might be gauged in terms of the key concept of “transformative” change.

While Prince has always pushed the legal boundaries of appropriation in his art making – arguably emboldened by his success in the Cariou V Prince litigation (2013) where he used a historical ethnographic image – last week’s ruling against Prince and the mega gallery Gagosian could set a precedent for how the fair use doctrine relates to online sharing apps.

The case of the Monkey Selfie

Can a monkey sue for copyright infringements over a selfie? That is the question that has faced the US federal court system this month.

A three-judge panel of the 9th US Circuit Court of Appeals in San Francisco heard the case on Wednesday 12 July. Last year, a ruling had been made against Naruto – a macaque monkey who, in 2011, snapped a selfie with an unattended camera that belonged to British nature photographer David Slater.

It was not until 2014, however, that the images became the subject of a complicated legal dispute, when Slater asked the blog Techdirt and Wikipedia to stop using his “monkey selfies” without permission.

Slater says the British copyright obtained for the photos by his company, Wildlife Personalities Ltd, should be honoured worldwide.

The websites refused, with Wikipedia claiming that the photograph was uncopyrightable because the monkey was the actual creator of the image, reported The Guardian.

Things became more complicated when Slater published a book with the US company Blurb, which included Naruto’s selfies. PETA (People for the Ethical Treatment of Animals) sued Slater in 2015 in the US court system on Naruto’s behalf, claiming the monkey was the copyright owner.

The lawsuit sought a court order allowing PETA to administer all proceeds from the photos for the benefit of the monkey.

The Daily Mail reported that the panel of judges ‘appeared puzzled by PETA’s role in the case, asking the group’s attorney why it should be allowed to represent the monkey’s interests’.

A judge ruled against PETA in 2016, saying that animals were not covered by the Copyright Act; but the organisation persisted.

Last week, the court of appeals heard oral arguments. If successful, this will be the first time that an animal is declared the owner of the property, PETA attorney Jeffrey Kerr said.

Their argument rests in the claim that ‘Naruto has been accustomed to cameras throughout his life and took the selfies when he saw himself in the reflection of the lens’.

Slater told The Guardian: ‘It wasn’t serendipitous monkey behaviour. It required a lot of knowledge on my behalf, a lot of perseverance, sweat and anguish, and all that stuff,’ adding that he wasn’t even sure Naruto was the monkey in the disputed photograph.

‘I know for a fact that [the monkey in the photograph] is a female and it’s the wrong age … Surely it matters that the right monkey is suing me,’ Slater said.

Among the points of contention were whether PETA has a close enough relationship to Naruto to represent it in court; the value of providing written notice of a copyright claim to a community of macaques; and whether Naruto is actually harmed by not being recognised as a copyright-holder.

‘There is no way to acquire or hold money. There is no loss as to reputation. There is not even any allegation that the copyright could have somehow benefited Naruto,’ said Judge N Randy Smith.

A ruling on the appeal has not been passed down.

What are the implications of Graham v Prince?

Just days later, on 18 July, a Manhattan federal court judge rejected the request by artist Richard Prince, Gagosian Gallery, and Larry Gagosian to dismiss the copyright infringement lawsuit of photographer Donald Graham.

The court denied the request.

While the facts of this case are very different to the Slater V PETA case, both have come about via the digitisation of images circulated online.

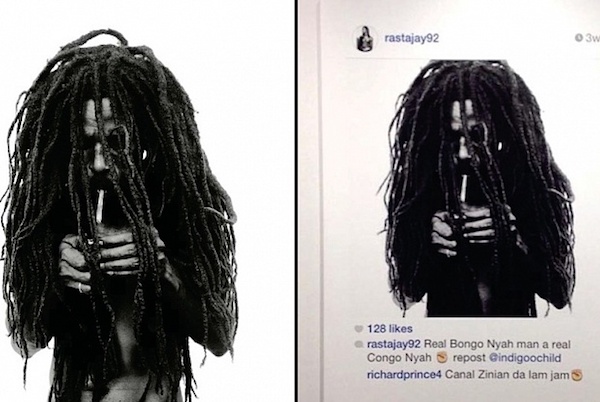

Graham alleges that Prince unlawfully used his photograph, Rastafarian Smoking a Joint (1996) by reproducing it as an enlarged Instagram post on canvas for his New Portraits exhibition at Gagosian Gallery in 2014.

Prince sourced the photograph from another user’s Instagram account. It also appeared in promotional material including the exhibition catalogue, a billboard, and in a post on Twitter. Graham first filed a cease-and-desist order against Prince, and then a lawsuit in 2015.

Donald Graham’s photography, left, and Richard Prince’s Instagram print, right

The Art Newspaper reports that four other lawsuits have been filed by other photographers also alleging the defendants infringed their work in the same exhibition.The defendants argued that Prince’s work, Untitled, was “transformative” of Graham’s image, and therefore non-infringing fair use, and that the judge could decide that by simply comparing the two works side-by-side.

US District Judge Sidney H. Stein, however, challenged that premise, stating that despite the slight cropping of Graham’s photograph and the addition of comments on the Instagram print, ‘The primary image in both works is the photograph itself. Prince has not materially altered the composition, presentation, scale, color palette and media originally used by Graham.’

He wrote: ‘Prince’s Untitled does not make any substantial aesthetic alterations to Graham’s Rastafarian Smoking a Joint.’

Chief Executive Officer, Australian Copyright Council (ACC), Fiona Phillips said that the Graham V Prince outcome offers, ‘A cautionary tale, given the recent story on ArtsHub about digitising your portfolio.’

Read: Is it time to digitise your portfolio?Once you make your work digitally available it can be “plucked and appropriated”, and with fair use laws still largely untested, artists need to be crystal clear on the implications of sharing their images.

Judge Stein noted that it would be unusual to dismiss a copyright suit so early in a case.

The judge said he ‘couldn’t determine whether Prince’s alterations gave a new expression or meaning’ to Graham’s original without substantially more evidence, such as art criticism and Prince’s own statements of his intention.

Phillips noted: ‘Interestingly, the fact that the Court did not yet have evidence before it about Prince’s artistic intent was a consideration in the use being found not to be “transformative” as a matter of law.’

Judge Stein compared the case before him to the Second Circuit Court of Appeals 2013 ruling concerning Prince’s transformative reproductions of Patrick Cariou’s photographs. In that case, it was found that 25 of Prince’s Canal Zone paintings were transformative of Patrick Cariou’s photographs in part because they had “an entirely different aesthetic”. Cariou’s images were described as “serene”, Prince’s as “crude”.

The ACC published the recent paper, The Prince of Fair Use: Putting the brakes on transformative use which concludes that the decision is interesting for a number of reasons: ‘For artists, it serves as a cautionary tale about protecting your work online. For those of us interested in the fair use doctrine, it emphasises that fair use is a question of both fact and law.

‘While Stein’s analysis of the Second Circuit’s opinion in Caroiu shows how important transformative use has become in US fair use jurisprudence, it also shows that merely alleging that your work is transformative will not be enough,’ the ACC points out.

While the US Court of Appeals decided in favour of Prince in 2013, it left an ambiguous precedent for determining fair use – one that Prince’s lawyer, Joshua Schiller is seizing: ‘The judge applied the wrong standard. We will be able to show fair use.’

The ACC says that the issues we are facing can be applied anywhere. Phillips asks: ‘Could the claim for copyright infringement be dismissed at an interlocutory stage based on a fair use defence?’

ArtsHub recommends you read the ACC summary of Judge Stein’s comments on the Graham V Prince case, and as its title suggest, consider ‘putting the brakes on transformative use’.