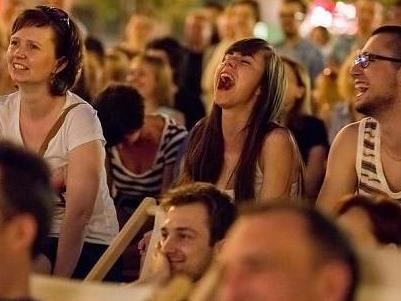

Malta Festival Poznan 2014. Photo Maciej Zakrzewski

‘Festivals rise up from the fibre of communities to create celebrations of scale, depth, and gravity. Festivals capture the best that communities create’ – Titus Levi, Economist/Arts Consultant

In April this year I attended the Atelier for Festival Directors in Edinburgh, with the question “What makes a festival a festival” in mind. Throughout the course of the Atelier, countless other questions, came, were explored, and then went, to be replaced with a seemingly endless list of more.

Back in Australia, and putting on my own festival for the fourth time, I’ve raised the question again, after realising, that for me, when I say festival, what I really mean is an event, or series of events, which have community at their heart. I came to this realisation, after looking through the programs of many Australian art-based festivals, and frankly not finding much that enticed me to a) spend money on b) leave my regional community for. I also found that quite a few online programs were extremely tricky to navigate, making me wonder if some Festivals didn’t really want to be accessible.

I am always surprised too, that many festivals tend to avoid any affirmation of families, children, people with special needs and young people, or if they do it is within a specially regulated section, (which often feels like an add on) rather than integral to the entire program.

I’m not sure how definitive I am of the general arts festival going public, but anecdotally at least, I’ve found that those I know are tending to question the content of the larger, more traditional festivals – we have either seen/heard/experienced it all before, (and usually for cheaper somewhere else) or are craving for something egalitarian, engaging, and free of hype.

Are community based festivals the Cinderellas of the Festival world? This is one question that was not examined, but if you look at the Festivals represented by Atelier mentors and attendees, a very low percentage were totally community centred. Many however, like the Malta Festival Poznan (which works with guest artistic programmers each year) successfully combine community based events with large scale international events. The London based Lift Festival too, under Artistic Director Mark Ball, is very much community driven, with a clear message that “we need to be doing more with the public, not for them.” This leads to another query of how (rather than should) festivals communicate with their audiences, and by what process audiences can inform programming.

For me, you can’t just parachute a Festival into a community – for it to take root, it needs to be planted, and grow upwards and outwards. And to stretch the analogy even further, it needs to be nurtured and valued in order for it to become strong – and head towards the holy grail of self-sustainability. (Although like a tree, without certain elements – it’s not going to survive; a community arts festival needs an audience, good-will, and funding of some sorts, to protect it from withering and dying!)

I believe when planning and preparing for a festival, it is imperative to ask yourself a few key things, before getting bogged down in the same old same old:

- Why you are doing this? If it is a community based Festival, then how are you celebrating your particular community, and what opportunities for real participation can you offer?

- Are you complicating things? Is getting bigger necessarily a good thing? There are many different models for Festivals. It’s a good thing to remind yourself of this, and to play with them. Take a look at non-arts Festivals. Usually these are streamlined affairs, with different priorities and ways of working. And work they do. Take the Griffith Salami Festival, a beautiful example of a Festival beginning from something authentic evolving organically, to bring a community together, in one long afternoon of camaraderie and carnivorism.

- Festivals, can, and do have a shelf life. If you’re festival is no longer relevant, than that is ok – it’s not a sign of failure, but one of awareness, and fulfilling a certain need that no longer (perhaps because of your well-directed festival) is there. Instead of trying to push water up hill, think about the legacy your Festival will leave, and move on – or re-invent yourself.

- As Jonathan Mills – Festival Director and Chief Executive, Edinburgh International Festival repeated often at the Atelier – Festivals are place makers. How does your festival define its location (and how does the location define the festival.) How can you use non-traditional venues and spaces to connect? Jonathan also reminded the Atelier that the need for ceremony and ritual stretches back to the beginning of human kind and that as programmers we should constantly remind ourselves of the importance of celebration and community in our festivals.

- What are you doing with your evaluation? Is it only there to satisfy your funders? Or can you really make it work for you. Are you really prepared to take on board criticism? Do you acknowledge when things don’t work –and use that experience to really educate your planning? And how can you assess the soft outcomes, the ones that really contribute to community well being and connection?

To return to my original question of what makes a Festival a Festival – personally it’s a the coming together of people of all ages and backgrounds and that, makes me feel like I belong and that I am part of something more. Can a community based Festival create community? Of course it can!